DUTY, HONOR, COURAGE, RESILIANCE

Talking Proud: Service & Sacrifice

Airborne Peripheral Reconnaissance, Cold War Losses

“Silent Sacrifices”

Introduction

The “Cold War” followed immediately after the end of WWII. It was a sustained state of political and military tension mainly between the US, the leader of the West, which included the NATO Western European nations, and the Soviet Union (USSR), as the leader of the East, which included the Warsaw Pact nations. Each of the leaders had nuclear weapons and the ability to deliver them.

The Cold War ran from roughly 1946-1947 through 1991. The WWII Alliance between the West and the East fell apart immediately after WWII. Each side set itself against the other.

The Soviets, having taken most of Eastern Europe and East Germany, set up what Winston Churchill called the “Iron Curtain.” In a letter to President Harry Truman, Churchill said, “[A]n iron curtain is drawn down upon their front. We do not know what is going on behind."

The fact that we did not know what was going on behind that curtain to the east formed the foundation of the need to find out. The requirement grew almost immediately to fly airborne reconnaissance over the USSR and around the periphery of the USSR and the Warsaw Pact.

After WWII, the West knew almost nothing about the Soviet Union. The US did not know where its bases were, what was there, and how best to get there if we should have to attack. The US did not even have good mapping data of the Soviet coastline. There were many challenges for the US, but fundamentally, the main challenge was to look as deeply into the Soviet Union as physically and militarily possible.

Both the US and the USSR were suspicious of each other and gravely worried about the other attacking them with nuclear weapons. Furthermore, each side wanted to strengthen its influence. The Soviets wanted to consolidate their power and build a buffer zone between themselves and Germany. To do this, they had to exert tight control over East Germany, and the US had to build its military strength in West Germany.

At first, each side worried about bombers, then they worried about intercontinental ballistic missiles (ICBMs), and later downstream submarine-launched ballistic missiles (SLBM). During the early Cold War, bombers and ICBMs would dominate.

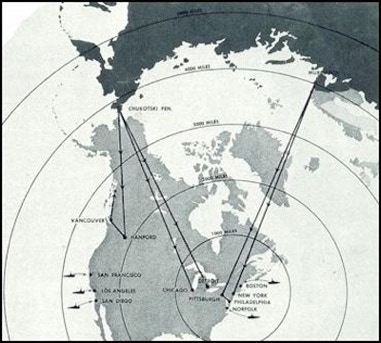

Initially, the US was the most anxious about Soviet attacks against Alaska and, as a result, concentrated on Siberia. But those concerns would rapidly expand to the possibility of Soviet nuclear attacks against the breadth of the US. The US had to know much more about the size, composition, and disposition of Soviet forces deployed behind the Iron Curtain. The US was especially interested in the state of Soviet air defenses, radars, anti-aircraft, surface-to-air missiles, and fighters.

As a result, in late 1946, the US began flying reconnaissance missions that collected signals intelligence (SIGINT), which included communications intelligence (COMINT), electronic (ELINT) intelligence, and photographic intelligence (PHOTINT). Collection by human means, known as human intelligence (HUMINT), went full speed ahead, but this was very dangerous and was hampered by false and deceptive observations and testimonies.

In 1947, the newly formed US Air Force (USAF) sought permission to fly over Soviet territories, especially over Siberia. The Joint Chiefs of Staff (JCS) rejected the idea. In 1948, the State Department restricted US reconnaissance flights to peripheral missions at standoff distances no closer than 40 miles.

During 1949 and 1950, the geopolitical landscape changed. Communist forces took over all of China, with nationalist forces allied with the US having to run to the island of Formosa, now known as Taiwan. All of Eastern Europe under Soviet influence and control became communist states. Then, in 1950, the North Korean communists invaded the Republic of Korea, and a full-blown war was underway through 1953. The prospects for a global communist movement grew, as did the probability that the Soviets might attack the US and Western Europe.

The Soviets could fly Tu-4 nuclear-equipped bombers located on the Chukotskiy Peninsula over Alaska on one-way missions to attack American population centers. Soviet bombers flying from the Kola Peninsula bordering Finland had the same capability. Among other things, the US had to find out exactly where the bombers were and, as importantly, figure out what routes would best penetrate the Soviet Union for a US bomber attack—said differently, where the Soviet air defense system was the weakest.

In December 1950, Truman authorized two deep penetration flights of the Siberian area. A B-47B bomber was taken off the assembly line for the mission. However, the airplane was lost on the ramp due to a fuel leak and fire. In the meantime, the British had formed a “Special Duty Flight” of three aircrews to fly US-manufactured RB-45Cs and, together with USAF crews, practiced from Barksdale AFB, Louisiana. Three aircraft painted with RAF insignia launched from an RAF base and flew separate tracks at night at 35,000 ft. over the Baltic states, Belorussia, and Ukraine. The Allies intercepted Soviet air defense communications (COMINT). The Soviets scrambled fighters, but the Soviet air defense system could not find the RB-45Cs. They all returned home safely with a treasure trove of photography of hundreds of different intelligence targets. They also found the Soviet air defense system incapable of handling such an intrusion.

The net result was the Soviet air defense system had weaknesses that must be exploited so that Western bombers could penetrate that Soviet system and destroy Soviet bombers before they could attack the West.

The US ramped up overflights as more information became available that the Soviets were deploying their Tu-4s throughout the Soviet Union. Fighter bases became increasingly active with state-of-the-art fighter aircraft like the MiG-15.

The Tu-4, shown here, was a carbon copy of the US B-29. The Soviets disassembled one of our B-29s that had made an emergency landing in the USSR during the war and duplicated the bomber, part for part. At first glance, this Tu-4 looks like a B-29.

Then, in 1954, as part of a Soviet May Day parade, the M-4 jet bomber first appeared flying over Moscow. That caused great concern, and the US sent flights over the Kola Peninsula in northern Russia to look for them.

The US and Britain continued overflights for many years, employing RB-45s, RB-47s, and even tactical reconnaissance aircraft. They encountered flak and MiGs. Early on, the MiGs did not attack, but as time passed, they began attacking. Surprisingly, the US and RAF aircraft could either elude the flak and fighters or outrun them at altitudes at which the fighters were ineffective.

Nonetheless, it became apparent that a new aircraft was required for such overflights. That led to the development and evolution of the U-2.

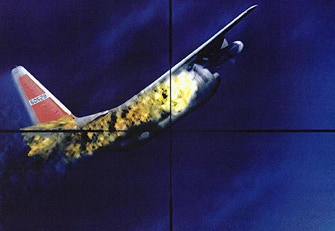

In late 1956, after the Soviets protested the flight of three RB-57Ds over the Vladivostok Maritime Region, President Eisenhower ordered the termination of the overflight program. He resumed employing the U-2 in 1957 but was forced to terminate it again after the Soviets successfully shot down a U-2 flown by Francis Gary Powers on May 1, 1960.

As the Soviets and their allies improved their air defense systems, overflight reconnaissance became less and less desirable and one best assigned to developing satellite capabilities.

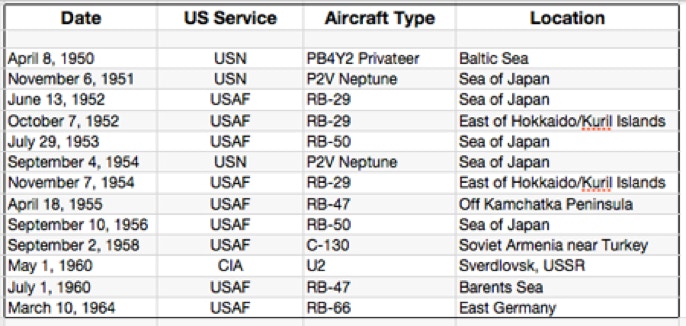

This report addresses peripheral reconnaissance losses to the Soviets during the early Cold War years. The missions that were lost to the Soviets carried varied intelligence collection packages.

Michael L. Peterson has written a thorough report on a group of losses entitled, “Maybe you had to be there: The SIGINT in Thirteen Soviet Shootdowns of US Reconnaissance Aircraft.” The National Security Agency (NSA) published his work in the Cryptologic Quarterly. It was classified at the Special Compartmented Intelligence (SCI) level but was declassified and approved for release by the NSA on May 8, 2012.

NSA is the national agency responsible for collecting SIGINT. The thrust of Peterson’s report is to show the evolution of SIGINT's role in helping to explain what happened during the losses of 13 US reconnaissance missions. I will address only 12 of these, leaving out the Francis Gary Powers U2 loss since so much has been written about it.

Let’s pause for just a moment. From 1950 to 1964, the NSA received considerable support and talent from the three military services in what were called Service Cryptologic Agencies, SCAs.

The USAF employed the major air command known as USAF Security Service (USAFSS) to serve in this role; the Navy used the Naval Security Group (NSG), and the Army assigned the tasks to the Army Security Agency (ASA). While each SCA followed its military department’s chain of command, it received its tasking from the NSA or from commands and agencies authorized by the NSA to task the SCAs. Quite often, an airborne crew would have pilots, navigators, electronic warfare officers, engineers, gunners, etc., assigned to a flying unit, while the SIGINT positions would be staffed by people from one of the SCA’s units. You’ll see some references as I proceed.

One more pause before we get going. Please keep three things straight in your mind.

First, the SIGINT provided mostly friendly intercepts of Soviet tracking of the reconnaissance aircraft and reacting fighters and friendly voice intercepts between the Soviet pilots and their ground controllers involved in the shoot-downs.

Second, many of these missions collected SIGINT, much of which was lost because they were shot down. The net result was that we often did not have access to the Soviet pilot-controller communications because of the shootdowns. However, we occasionally had ground stations close enough to the action that were equipped and designed to handle line-of-sight VHF communications.

Finally, the US employed cover stories for these missions. For example, some were said to be weather reconnaissance, navigational training, and mapping reconnaissance. In other cases, the US would acknowledge the mission was a photography mission, but one did not always know precisely all the kinds of equipment that may have been on board.

This report will address the 12 losses shown in the chart above. I will attempt to blend Peterson’s SIGINT intercepts of Soviet communications information with operational and friendly radar reports to give you a full view of what happened during these flights and attacks. In a few cases, survivors added some information to the stories.

Please note that I only discuss missions targeted against the USSR and Soviet reactions. Remember, we will only be talking about missions peripheral to the USSR. Many similar missions were flown against China, North Korea, and North Vietnam, but I will not address those.

It is important to recognize that, for the most part, the peripheral reconnaissance missions were conducted in great secrecy. The SIGINT missions were especially secretive because of the character and importance of the cryptologic information and methods we employed. I point this out because the crews involved were “Silent Warriors.” They often flew unarmed, without escort, often on radio silence, and frequently at considerable distances from friendly airfields and search and rescue support. Those who perished and those who did not, and the many still doing this kind of work today, receive little notice and accolade. It is important, I believe, to read this report and remember the sacrifices they made and continue to make.

Well, at long last, let’s get started.

Soviet air defense fighter aircraft first attacked a USAF RB-29 ferret mission over the Sea of Japan in October 1949, but the RB-29 escaped unhurt. The word “ferret” means “to search out tenaciously.” For political reasons, the US did not use the term “reconnaissance” in these early days, preferring to call them ferret missions. Peterson wrote that over 23 years, the Soviets made 30 documented attacks on US reconnaissance aircraft and even more on Allied aircraft conducting similar missions. The first successful shootdown occurred on April 8, 1950, and the last on March 10, 1964.

Let’s see what we can learn about 12 of these.

__________

Click to zoom graphic-photo

Table of Contents

- Introduction

- USN PB4Y2, Baltic Sea, April 8, 1950

- USN P2V Neptune, Sea of Japan, November 6, 1951

- USAF RB-29, June 13, Sea of Japan, June 13, 1952

- USAF RB-29, Sea of Japan, October 7, 1952

- USAF RB-50, Sea of Japan, July 29, 1953

- USN P2V, Sea of Japan, September 4, 1954

- USAF RB-29A , Sea of Japan, November 7, 1954

- USAF RB-47 , off-shore Kamchatka Peninsula, April 18, 1955

- USAF RB-50G , Sea of Japan, September 10, 1956

- USAF C-130A , Soviet Armenia, September 2, 1958

- USAF RB-47H , Barents Sea, July 1, 1960

- USAF RB-66C , East Germany, March 10, 1964