DUTY, HONOR, COURAGE, RESILIANCE

Talking Proud: Service & Sacrifice

Airborne Peripheral Reconnaissance, Cold War Losses

“Silent Sacrifices”

USAF RB-50, Sea of Japan, July 29, 1953

Two Soviet MiG-15s shot down a USAF RB-50G (47-145), crew of 17, over the Sea of Japan about 70 miles southeast of Vladivostok during the morning of July 29, 1953. The aircraft and most crew were from the 343rd SRS at Forbes AFB, Kansas, temporarily attached to the 91st SRS at Yokota, Japan. There were two 1st Radio Mobile Squadron members, Johnson AB, Japan, on board as well. They were Russian linguists tasked to intercept Russian voice communications.

This particular RB-50G was nicknamed “Little Red Ass.” Legend has it “Little Red Ass” at the time was USAF jargon for “I don’t want to be here.”

Official Air Force reports say two Soviet MiG-15 fighters shot the RB-50 down. The Soviets have admitted they did shoot it down. Other sources say they were MiG-17s, but the consensus is they were MiG-15s.

The RB-50 was a version of the B-29 with updated Pratt & Whitney R-4360 radial engines, a more robust structure, a taller vertical stabilizer, and quite a bit of Signals Intelligence (SIGINT) intercept equipment on board.

Three different configurations were produced, which were later redesignated: RB-50E, RB-50F, and RB-50G, respectively. The RB-50E was earmarked for photographic reconnaissance and observation missions; the RB-50F resembled the RB-50E but carried the SHORAN radar navigation system designed to conduct mapping, charting, and geodetic surveys.

The mission of the RB-50G, which also had the SHORAN radar, was SIGINT reconnaissance. The RB-50Gs operating from Yokota AB, Japan, were Communications Intelligence (COMINT) birds. There were also some Electronic Intelligence (ELINT) aircraft.

The website Aircrew Remembered reported that this RB-50 G's mission on July 29, 1953, was to “investigate radar facilities along the Soviet border.” The USAF said the RB-50G was on a routine navigational training exercise in international airspace.

Capt. Stanley K. O’Kelley (left) was the pilot and aircraft commander. Capt. John Roche (right) was the co-pilot. The rest of the crew included Major Francisco J. Tejeda (ECM), Capt. James G. Keith (nose navigator), Capt. Robert E. Stalnaker (ECM), Capt. John C. Ward (ECM), Capt Lloyd C. Wiggins (radar navigator), Capt. Frank E. Beyer (ECM), Capt. Warren J. Sanderson (ECM), Capt. Edmund J Czyz (radar navigator), SSgt. Donald W Gabree (central fire control specialist who remotely controlled five electronically controlled machine guns), A2C Earl W Radlein, and SSgt.Donald G. Hill (both Russian linguists and intercept operators), A1C Roland E. Goulet (waist gunner), A2C Charles J Russell (waist gunner), A2C James E. Woods (gunner), MSgt. Francis L. Brown (flight engineer).

SSgt. Hill (left) and A2C Radlein (right) were from the 1st Radio Mobile Squadron, Johnson AB, Japan, a unit of the USAF Security Service (USAFSS) which conducted SIGINT operations for the USAF and others, including the National Security Agency (NSA). Hill and Radlein were the first USAFSS people to be killed in the line of duty. They were both Russian linguists.

The RB-50 departed Yokota AB, Japan, at 0307 hours on July 29, 1953. The MiG-15s attacked her at 0615 hours. NSA said the RB-50 had completed its mission and was on its way back to Yokota when intercepted by the Soviet fighters.

The USAF Military Personnel Center (AFMPC) published over 440 documents related to this shootdown. The documents include correspondence between families of those lost and US officials, including President Kennedy. It also contained a Department of State formal diplomatic claim against the Soviet government regarding the loss of this RB-50. I will draw from this claim to convey the events during this flight and engagement.

The RB-50 was flying at 20,000 ft. altitude on an easterly heading about 40 miles south of the Soviet landmass when, at about 0615 hours local time, two Soviet MiG-15s “intercepted and fired upon” it.

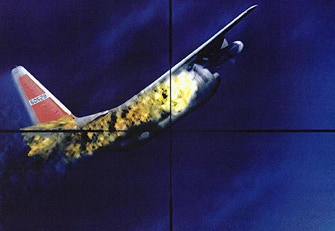

The report said that one MiG-15 approached the RB-50 from below to its left. Its hostile fire struck the #1 engine, the left engine, rendering it inoperative. Then, one or more MiG-15s approached from the rear and fired, hitting the #4 engine on the right, the right-wing, and other portions of the aircraft, causing the engine to burst into flames. In response, the RB-50 crew opened fire on the MiGs.

The RB-50 dove sharply and quickly lost altitude. The right-wing and tail section tore off, causing the aircraft to disintegrate. The aircraft hit the water at about the same location as where it was intercepted, and about two minutes elapsed from when it was hit and crashed.

The Aviation Safety Net reported the engagements occurred seven miles south of Askol Island, near Vladivostok. The Soviets said that she had violated Soviet airspace near Cape Gamov. This account continued,

“According to Soviet reports, the fighter pilots instructed the aircraft to land, but the gunners opened fire and hit the MiG flown by 1st Lt. Aleksandr D. Rybakov, who subsequently attacked the RB-50 together with his wingman 1st Lt. Yuri M. Yablonskiy and shot it down with cannon fire. US reports claim the interceptors opened fire first, disabling the RB-50’s #1 engine. The gunners then only returned fire in self-defense but could not prevent another attack that set the #4 engine on fire. The RB-50 reportedly went in a sharp dive, parts of the damaged right wing and tail assembly tore off, and the aircraft disintegrated and crashed into the sea about two minutes after being fired upon.”

The Soviets said the RB-50 opened fire after being told to leave Soviet airspace, causing damage to one of the fighter’s fuselage and wings.

The State Department filing said Capt. O’Kelley ordered the crew to bail out. Only Lt. Keith did not bail out. He reportedly was killed after being thrown around inside the aircraft.

MSgt. Brown bailed out but died as a result of shock and prolonged exposure to the water. Capt. Roche, the co-pilot, and the pilot, Capt. O’Kelley bailed out together and landed in the water close to each other. Roche held on to O’Kelley, but the latter died in Roche’s presence.

The bodies of O’Kelley and MSgt. Francis L. Brown were recovered “along the coast of Japan.”

Roche suffered some injuries as the result of being thrown into the body of the aircraft, but he bailed out and floated in the water, holding on to aircraft debris. A USAF Air Rescue Service SB-29 (such as shown here) spotted him and dropped him a life raft. The SB-29 was known affectionately as the “Super Dumbo.” She had an air-droppable EDO A-3 lifeboat rigged underneath. Roche was able to get in it. A USN ship rescued him the next day at 0400 hours, about 22 hours after he bailed out. Getting the life raft no doubt saved him.

The US destroyer, USS Picking (DD 685), in the company of an Australian destroyer, the Tobruk, picked up Roche. Capt. O’Kelley was also recovered by the Picking but died of injuries and exposure.

In sum, USAF could account for four crew members: Capt. O’Kelley, Capt. Roche, Lt. Keith, and MSgt. Brown. It said the remaining 13 crew “successfully parachuted to the surface of the Sea of Japan and were either picked up by the Soviets or they died in the water. Their bodies were not found.”

Search aircraft spotted “at least 12 Soviet PT-type boats, at least one armed, trawler-type Soviet vessel, and Soviet aircraft going to and from the scene “at high speed.” The State Department filing of charges concluded that “Soviet craft picked up survivors and portions of the disabled B-50 aircraft.” The USAF later declared the missing men KIA.

I have seen several renditions of what Capt. Roche saw. One is that Roche had not seen any Soviet ships in the area, which indicates that the Soviets had not rescued any of the crew. A second is that he later said, “Several Russian boats were in the area immediately after the crash, and crew members of the rescue planes searching the site also reported sightings of Russian boats and planes in the area that may have picked up other possible survivors or remains.” And a third, he believed the engineer, navigator, and probably the tail and waist gunners parachuted out successfully. Roche is said to have reported he could hear shouting in the distance while in the water.

I find the second rendition closest to what happened.

I have read reports saying the aircraft was shot down 26 miles off Cape Povorotny, and three bodies washed ashore.

The fog of war is evident and understandable. The NSA also found it challenging to wade through the fog of war.

Michael L. Peterson wrote a story entitled “Maybe You Had to Be There,” published by Cryptology Quarterly. Peterson was the Center for Cryptologic History historian at the National Security Agency (NSA). The report has been declassified.

Peterson wrote that SIGINT intercepts indicated that the Soviets watched events starting about 30 minutes before the shootdown on July 29, 1953, and extending for about 54 hours after that into July 31. This indicated they closely watched American and Soviet rescue and recovery efforts.

At first, an intercept station in Japan reflected Soviet air defense facilities passing 14 positions on the aircraft to the south and southeast of Askio Island. The Soviet tracking showed the RB-50 as far north as 42 degrees 25 minutes north latitude, above the planned course south of the 42nd parallel. This meant the Soviets thought the RB-50 was north of the 42nd parallel, as far as 42 degrees 25 minutes north latitude.

NSA followed up on this initial report and said the Soviets intercepted RB-50 at 42 degrees 18 minutes north latitude. Three years later, a report was issued that the RB-50 was intercepted about 12 miles southeast of Cape Gamova. I am not able to interpret this tracking.

We can surmise that the RB-50 was collecting intelligence against Soviet military targets in the Vladivostok region, the location of the Soviet Union’s most important naval base, the center of Soviet nuclear submarine operations, and the second largest commercial port in the eastern USSR. The Soviets had closed it off to foreign visitors.

Capt. Roche, the co-pilot, insisted they were 40 miles out, well beyond Soviet airspace, and said they were attacked without provocation or warning.

We cannot know for sure since we cannot access the RB-50’s flight logs.

The Soviets showed considerable interest in rescue operations. They tracked US rescue aircraft for thirty minutes, starting four and one-half hours after the shootdown. They also tracked aircraft for five hours, eleven to sixteen hours after the shootdown, and for five hours again on July 30, the next day. The tracking included IL-28 bombers reconnoitering the area over 21 hours on July 30.

NSA said the Soviets “dispatched seventeen naval vessels, including the cruiser Kalinin, two each destroyer and submarines, and three each minelayer, minesweepers, sub chasers, and thirteen aircraft of various types from the morning of July 30 until noon July 31.”

The flight and demise of this RB-50 left some hard lessons learned for the US, ones that would develop over time to protect aircrews. Following this loss, a decision was made to put Russian linguists with some intercept gear aboard all bombers, tasking the operators to warn the pilots of approaching Soviet aircraft.

As an aside, the SIGINT collection during the reconnaissance flights in this area was paying dividends. Several Soviet Air Force operational ciphers, including the headquarters in Moscow, were broken quickly. US Army cryptanalysts were reading the encrypted radio traffic of the Soviet 9th Air Army and 10th Air Army in the Far East.

__________

Click to zoom graphic-photo

Table of Contents

- Introduction

- USN PB4Y2, Baltic Sea, April 8, 1950

- USN P2V Neptune, Sea of Japan, November 6, 1951

- USAF RB-29, June 13, Sea of Japan, June 13, 1952

- USAF RB-29, Sea of Japan, October 7, 1952

- USAF RB-50, Sea of Japan, July 29, 1953

- USN P2V, Sea of Japan, September 4, 1954

- USAF RB-29A , Sea of Japan, November 7, 1954

- USAF RB-47 , off-shore Kamchatka Peninsula, April 18, 1955

- USAF RB-50G , Sea of Japan, September 10, 1956

- USAF C-130A , Soviet Armenia, September 2, 1958

- USAF RB-47H , Barents Sea, July 1, 1960

- USAF RB-66C , East Germany, March 10, 1964