DUTY, HONOR, COURAGE, RESILIANCE

Talking Proud: Service & Sacrifice

Airborne Peripheral Reconnaissance, Cold War Losses

“Silent Sacrifices”

USAF RB-29, June 13, Sea of Japan, June 13, 1952

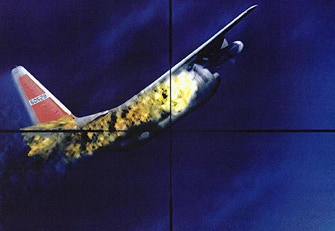

On June 13, 1952, Soviet MiG-15 fighters shot down a USAF RB-29 (s/n 44-61810) over the Sea of Japan near the Kamchatka Peninsula. There were 12 souls aboard. No remains or survivors were recovered.

This crew was from the 91st SRS. Their RB-29, nicknamed “Southern Comfort,” launched out of Yokota AB, Japan, at 1007 hours. The Cold War Museum has said, “Official records state that the aircraft was on a classified surveillance mission of shipping activity over the Sea of Japan.”

Radar contact was lost at 1320 hours, and the aircraft failed to return to base.

Jim Bard, Capt., USAF (Ret.) writing “Airplane crashes, 91st SRS Losses,” for the Korean War Educator, said it was shot down by a MiG-15 south of Mys Ostrovnoy about 120 miles from the Russian coast. This is the same area where a Navy P2V Neptune was lost. Wikipedia said Captain Oleg Piotrovich Fedotov and 1st Lieutenant Ivan Petrovich Proskurin flew the MiGs.

Bill Welch of the 31st and 91st SRS reported that this aircraft carried “special photographic” capabilities, which he called “the monster camera.” This was the K-30 aerial camera with a focal length of 100 inches and taking a 9x18 inch photo. It was a giant camera system, too big to fit in the camera department. A special floor was built into the forward bomb bay. It shot out the left side of the aircraft. Welch said,

“We photographed practically every mile of coastline from Hong Kong to Port Arthur. And from Vladivostok up to Kamchatka and back. We were frequently intercepted by fighters, MiG-15s, along the Chinese coast (We once got a good K-30 shot of one flying about a mile off our wing) and Soviet prop-driven Yak-9s and LA-5s up north of Japan. We managed to get away in every case.”

Welch also wrote that two special RB-29s came to Yokota AB and were assigned to C Flight, sometimes called the “Cloak and Dagger Flight.” These aircraft, equipped with the K-30 camera, were put under guard. The same crews always flew them.

Colonel George W. Goddard, the Air Force Chief, Photographic Laboratory, in a paper entitled “New Developments for Aerial Reconnaissance,” circa 1949, said the 100-inch camera provided high definition, performed very well mechanically, and “would have been extremely valuable for pinpoint photography during the last war (WWII).” He pointed out that it could have provided “the definition and scale required at 32,000 feet altitude.”

This is a photo of the crew that was lost. L to R, Front Row: 1st lt. Robert J. McDonnell, Navigator; SSgt. Roscoe G. Becker, Right Scanner; SSgt. Eddie R. Berg, Tail Gunner; Leon F. Bonura, Left Scanner; MSgt. William H. Homer, Flight Engineer. L to R, Back Row: 1st Lt. Samuel D. Service (posthumously promoted to captain), Radar Operator; 1st Lt. James A. Sculley, Pilot; Major Samuel N. Busch, Aircraft Commander; SSgt. William A. Blizzard, Radio Operator; SSgt. Miguel W. Monserrat, Central Fire Control Gunner; A1C Danny Pillsbury, Camera Operator. TSgt. David L. Moore is not in the photo but flew aboard the ill-fated mission.

A Morning Call Staff Report of November 12, 1995, provided this insight,

“What (Major Sam) Busch (aircraft commander) never told his wife was that after six reconnaissance flights over North Korea, he and his B-29 crew had received their diciest assignment: bait the Soviet Union with a flagrant violation of Russian air space on a secret mission to determine the strength of Soviet electronic intelligence.”

Radio intercept operators in Japan intercepted transmissions from Soviet aircraft, reporting they had shot down this RB-29. Philly.com reported Major Busch’s last words heard on the radio were, “Let’s get out of here.”

Soviet archives later confirmed two MiG-15 fighters shot down this aircraft. At the time, the only Soviet aircraft that had a chance against the RB-29 was the MiG-15.

The Cold War Museum said a Search and Rescue (SAR) mission was conducted on June 14, and an empty six-man raft, right side up, was sighted about 75-100 miles off the Soviet coast, but weather conditions prevented salvaging the raft.

The RB-29 usually carried three six-man rafts, eleven one-man life rafts, food, and medical supplies.

The Museum also noted,

“An unconfirmed report indicated that a second six-man life raft was seen four miles south of the first raft, but this sighting could not be verified. The search continued until June 17, 1952, but no wreckage was found, and no survivors were sighted.

“This downing was considered an ‘Air Accident’ according to official records. The crew members were continued in a missing status until November 14, 1955, when their status was ‘administratively’ changed by the Department of the Air Force to ‘deceased by presumptive finding of death.’

“Throughout the years, there have been many rumors about the crew of this RB 29. In the spring of 1953, a Japanese prisoner repatriated from a labor camp in Khabarovsk speaks of 12 or 13 U.S. airmen who were held with him. There were rumors of an officer from a B-29 being seen in a Soviet hospital in Magadan (a port town on the Sea of Okhotsk). Members of a flight that was shot down in July of 1952 were interrogated by the Chinese about Major Busch.”

In a hearing held on June 20, 1996, by the House Committee on National Security, Congressman John Fox of Pennsylvania told the chairman, “In 1992, President Yeltsin admitted that the plane had been shot down and that some airmen had been taken prisoner and may still be alive. Their fate is still unknown.” Later, one of Yeltsin’s generals said that there was only a possibility that captured servicemen were alive.

The families of the crew were told the aircraft had vanished.

The Washington Post reported on October 19, 1995,

“The State Department in 1956 told Moscow it was ‘informed and compelled to believe’ that one or more members of the RB-29 crew were held by the Soviets. The Soviet government denied it had the men.

“In 1993, Russian documents surfaced that made clear that two MiG-15 fighters shot down the U.S. plane over coastal waters off Vladivostok. It remains to be explained what happened to the men, although they are presumed dead.

“A State Department message to Moscow dated July 16, 1956, stated that evidence indicated an officer from the RB-29 crew was seen in October 1953 in a Soviet hospital in Siberia. The note did not name the officer or describe the basis of the information.”

As far as I can tell, this entire event remains a mystery. The USAF has declared the crew dead.

However, I found a most curious story by Roland Robitaille, a former B-29 tail gunner. Robitaille was part of a B-29 crew sent to the Sea of Japan to search for the missing RB-29 “Southern Comfort.” He reported seeing an RB-29 sitting in the water. The left gunner said he saw the same thing. Robitaille said,

“He saw the two open doors to the life raft compartments, and they were empty. They are situated above the wings in the fuselage … The left gunner remembers seeing something like boxes or crates floating in the water … We continued searching, and as darkness fell, low scud clouds began to form, making it difficult to see. We kept looking in hopes that we might see a flare, but no such luck. Fuel was getting low, so we had to return to base. During interrogation, the interrogating officers asked questions of the officers, but never did ask the six enlisted men any questions.”

Years later, Robitaille reported what he saw to the Department of Intelligence and Foreign Affairs (DIFA). To my knowledge, nothing came of Robitaille’s report.

The RB-29 began flying Signals Intelligence (SIGINT) missions in 1948. As a general rule, in those days, Soviet fighters could not operate at the altitude flown by the RB-29. Most initial missions were flown by the 72 SRS from Ladd AFB, Fairbanks, Alaska, against the Soviet Far East and Siberia. Early missions carried photographic and SIGINT equipment. These initial missions did not produce much.

On August 5, 1948, President Truman authorized the RB-29s to overfly the USSR. They would cover 5,000 miles and operate up to 35,000 ft. These missions discovered that the Soviets had significant gaps in their air defense radar coverage, and the RB-29s began exploiting that, going in deeper and deeper. Finding gaps in radar coverage was crucial for the US strategic nuclear bombers identified to strike targets in the USSR.

The MiG-15 jet fighter was among the best air superiority aircraft in the world at the time, if not the best, rivaled only by the US F-86 Sabre (shown here). She could operate at 50,850 ft. The MiG-15’s mission was to intercept and kill USAF B-29s, which posed a strategic atomic threat to the Soviet Union. In the Korean War, the B-29 caused the North Koreans the most problems keeping their logistics and supply lines open. The MiG-15 was employed against the B-29s and caused considerable trouble for our bombers until the F-86 arrived.

The major problem the American pilots in Korea faced with the MiG-15 was that they knew precious little about it. They knew it could fly higher than their F-86 Sabre; they knew it was fast; they knew they flew in massive formations at high altitudes; they knew that they required ground intercept controllers to guide them, and, thankfully, they would learn after some missions that it was very unstable in a dive.

__________

Click to zoom graphic-photo

Table of Contents

- Introduction

- USN PB4Y2, Baltic Sea, April 8, 1950

- USN P2V Neptune, Sea of Japan, November 6, 1951

- USAF RB-29, June 13, Sea of Japan, June 13, 1952

- USAF RB-29, Sea of Japan, October 7, 1952

- USAF RB-50, Sea of Japan, July 29, 1953

- USN P2V, Sea of Japan, September 4, 1954

- USAF RB-29A , Sea of Japan, November 7, 1954

- USAF RB-47 , off-shore Kamchatka Peninsula, April 18, 1955

- USAF RB-50G , Sea of Japan, September 10, 1956

- USAF C-130A , Soviet Armenia, September 2, 1958

- USAF RB-47H , Barents Sea, July 1, 1960

- USAF RB-66C , East Germany, March 10, 1964