DUTY, HONOR, COURAGE, RESILIANCE

Talking Proud: Service & Sacrifice

Airborne Peripheral Reconnaissance, Cold War Losses

“Silent Sacrifices”

USN P2V, Sea of Japan, September 4, 1954

Two Soviet MiG-15s from Unashi, near Vladivostok, USSR, intercepted and shot down a Navy Patrol Squadron 19 (VP-19) P2V (Neptune) on a Fleet Air Reconnaissance Squadron 1 (VQ-1) mission over the Sea of Japan on September 4, 1954. Her home base was Atsugi Naval Air Station (NAS), Japan.

The Aviation Safety Network has a good summary.

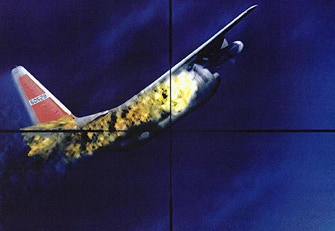

The P2V Neptune was over international waters southeast of Cape Ostrovnoi, 33 miles from Soviet territory. She was at 8,000 ft., speed 180 knots, heading 067 to the northeast. The MiGs approached from the rear and, at 0612 hours, opened with cannon fire. The P2V pilot immediately turned away from the Soviet landmass and entered a steep dive of 2,000-3,000 ft. per minute as an evasion attempt. The P2V conducted numerous evasive maneuvers. The skipper reached a cloud bank, hoping to hide.

The P2V was at about 3,000 ft. altitude when the MiGs conducted three more firing passes. They headed back to base, but the Neptune was hit on the third pass, with its port wing on fire. The fire quickly spread through the wing to the fuselage.

The skipper ditched her about 40 miles off the coast of Siberia. This area was a favorite reconnaissance flight area and an area where the Soviets attacked US military flights. In short, it was a dangerous place to fly.

The P2V had ten souls aboard. Ensign Robert Reid, the navigator shown here, drowned. He stayed aboard the aircraft, trying to push life rafts out the door to the others. It is believed Reid went down with the aircraft when it sunk, which occurred shortly after that.

The other nine of the ten aircrew were rescued by a USAF SA-16 amphibian aircraft the next day, on September 5.

They were Cdr. John B. Wayne, aircraft commander, Ens. John C. Fischer, co-pilot, Machinist’s Mate William A. Bedard, Aviation Electronics Machinist’s Mate 3rd Class Frank E. Petty, Aviation Electronics Technician Anthony P. Granera, Aviation Electronic Technician 3rd Class, Texas R. Stone, Chief Aviation Machinist’s Mate Paul R. Mulhollem, Aviation Ordnanceman Ernest L. Pinkevich and Aviation Electronics technician 1st Class David A. Atwell.

The Hampton Roads Naval Museum quoted Radioman Third Class Frank Petty after the shootdown,

“The Reds made three passes. On the second pass they scored a hit on the Neptune’s left wing, blasting a hole the size of a dinner plate in the wing, about six feet from where I was … We fired back. We started firing when they came at us the second time, but we only had two .50 caliber machine guns, and one of them jammed.”

The Minneapolis Morning Star Tribune quoted Aviation Ordnanceman Ernest L. Pinkevich in its September 6, 1954 edition,

“The only warning they gave us was coming in over our tail and shooting at us … They missed us on the first pass by about six feet. The tracers were going under our wing. They hit us on the second pass, but we turned away on the third.”

It also quoted Machinist’s Mate William A. Bedard,

“I was manning the top turret. I kept a close eye out, but I couldn’t see very well with the sun in my eyes. But then I saw a flash across the sun and saw a plane making a high, sweeping turn past our tail. I hardly had time to alert the skipper when I saw tracers coming at us.”

Aviation Electronics Machinist’s Mate 3rd Class Frank E. Petty was quoted by Bob Sherrill for the Austin American,

“Sure we fired back. We started firing when they came at us the second time. But we only had two .50 caliber machine guns, and one of those jammed.”

Petty then talked about ditching the aircraft,

“When we hit the water, we must have been doing about 100 miles an hour. The plane broke in two, right behind the after hatch, and I got a mouthful of water … I remember Texas Red (Aviation Electronic Technician 3rd Class, Texas R. Stone ) said to me, ‘Looks like a nice night for a swim’ … When everyone was aboard the raft, we counted noses and found Ensign Reid was missing. He must have tried to go back to the plane for the other raft and gone down with the plane. The last I saw of Reid was right after the plane caught fire, and he handed me the SOS message he wanted to be sent… We did hear searching aircraft, and we found later that it wasn’t US planes. I hate to think what might have happened if the Russians had spotted us … Then, about 6:30 am, just as dawn was starting, that beautiful B29 flew in and fired a recognition flare. It was the greatest sight I’ve ever seen.”

Sherrill reported that the B29 circled overhead until four Albatross and a P2V arrived and rescued the men.

The son of Chief Aviation Machinist’s Mate Paul R. Mulhollem, Britt McKinley Mulhollem, has written this about Ensign Reid’s bravery:

“Ensign Reid remained inside the plane to try to push the raft out to my dad (who was already in the water) but at some point must have realized that the plane was going under, and fast! My dad responded to the urging of Ensign Reid, and backed away from the plane, just in time to swim clear before the plane went down. He later said, ‘It went down in about 30-40 seconds, it went down like a Rock!.’ When they looked for Ensign Reid, he was gone. He obviously could have left the doomed plane, and swam to safety of the little raft, but chose to stay and try to release the larger safer raft, giving them a better chance to survive. We feel he should be recognized and his family should know that he indeed was a hero to my dad, and I have no idea if the other crew members consider him to be the hero my dad did, but all you have to do is read the accounts, and you could only come to one conclusion! Ensign Reid died a hero! And I think his family should know it!”

One letter from Britt McKinley Mulhollem said Ensign Reid’s last words were, “Get Out, Chief!"

The Soviets initially identified the P2V as suspicious and then hostile. The Neptune crew managed to get some shots off after being hit. One MiG pilot reported being hit, and four minutes after the attack, on his way back to his home field, he reported, “oil (pressure in the engine) is 20, only 20.” He managed to bring her in safely nonetheless.

The Soviets acknowledged shooting the P2V down but said the Neptune “violated the state frontier of the USSR in the region of Cape Ostrovnoi to the east of the Port Nakhodka … (and) opened fire on the Soviet airplanes.”

The National Security Agency (NSA) said, “No timely Communications Intelligence (COMINT) reporting could be found that directly covered the September 4, 1954 incident.”

NSA continued, saying USAF Security Service (USAFSS) “later published a study that indicated that two minutes before the attack, the Navy Neptune was located more than twenty nautical miles from the Soviet coastline, but it was heading directly north toward the Soviet coastline. COMINT had reflected the Soviet air surveillance radar tracking stations changing the designation of the Neptune from ‘suspicious’ to ‘hostile.’ Tracking indicated that the ill-fated aircraft turned southwest and continued to fly for another seventeen minutes before apparently crashing into the sea.”

The US took the case to the UN Security Council and the International Court of Justice.

__________

Click to zoom graphic-photo

Table of Contents

- Introduction

- USN PB4Y2, Baltic Sea, April 8, 1950

- USN P2V Neptune, Sea of Japan, November 6, 1951

- USAF RB-29, June 13, Sea of Japan, June 13, 1952

- USAF RB-29, Sea of Japan, October 7, 1952

- USAF RB-50, Sea of Japan, July 29, 1953

- USN P2V, Sea of Japan, September 4, 1954

- USAF RB-29A , Sea of Japan, November 7, 1954

- USAF RB-47 , off-shore Kamchatka Peninsula, April 18, 1955

- USAF RB-50G , Sea of Japan, September 10, 1956

- USAF C-130A , Soviet Armenia, September 2, 1958

- USAF RB-47H , Barents Sea, July 1, 1960

- USAF RB-66C , East Germany, March 10, 1964