DUTY, HONOR, COURAGE, RESILIANCE

Talking Proud: Service & Sacrifice

Airborne Peripheral Reconnaissance, Cold War Losses

“Silent Sacrifices”

USAF RB-29, Sea of Japan, October 7, 1952

Two Soviet La-11 fighters shot down an RB-29, serial no. 44-61815, nicknamed “Sunbonnet,” 9th SRS, on October 7, 1952. The fighters shot her down off the east coast of Japan’s northernmost island, Hokkaido, near the tip of the Kurile Island chain. Some sources have referred to this aircraft as “Sunbonnet King.”

Dr. Robert D. Eldridge, reporting for Japan Forward, said the RB-29 Sunbonnet went down “Near Yuri Island in the Habomai Island group, islands illegally seized by the Soviet Union in September 1945 after Japan's surrender.”

There were eight souls aboard. The aircraft’s home base was Yokota AB, Japan.

The crew consisted of Captain Eugene M. English, pilot; Captain John R. Dunham, navigator; 1st Lt. Paul E. Brock, co-pilot; and crew members Sgt. Samuel A. Colgan, SSgt. John A Hirsch, A1C Thomas G. Shipp, A2C Fred G. Kendrick, and A2C Frank E. Neail III. Capt. Dunham’s remains were returned to the US. The rest of the crew has not been found.

This is an engaging story for several reasons.

This marked the second time in 1952 that the Soviets shot down an RB-29 over the Sea of Japan, the first being the shootdown of RB-29 serial no. 44-61810, “Southern Comfort” on June 13, 1952. Both aircraft carried “special photographic” capabilities, the K-30 aerial camera with a focal length of 100 inches and a 9x18-inch photo. This camera system provided high definition from high altitudes.

Twelve souls were aboard Southern Comfort, and eight were aboard Sunbonnet. In total, twenty Airmen were lost. The remains of 19 were never found.

Second, this loss was a lesson in geopolitics, greatly influenced by geographic factors.

The Soviets entered WWII against Japan on August 8, 1945, two days after the US dropped the atomic bomb on Hiroshima and one day before the US dropped another on Nagasaki. President Truman feared the Soviets would send its military forces into Japan and claim their “war prize.”

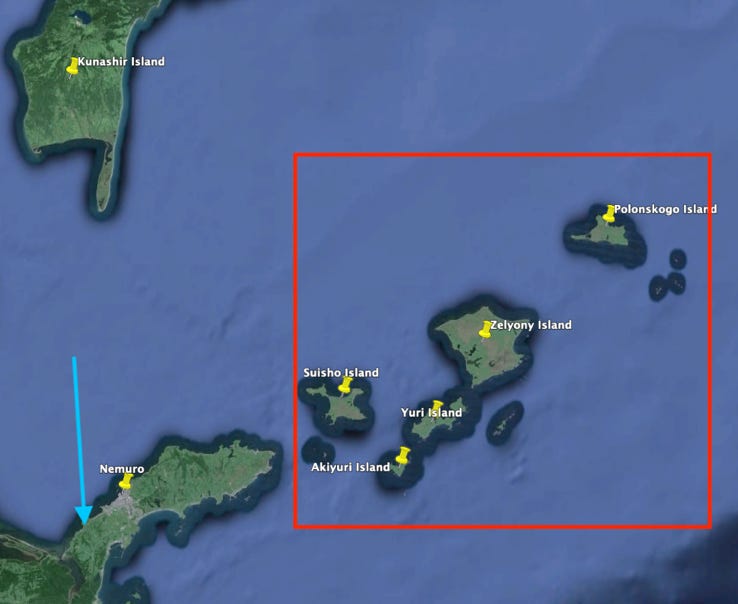

The Soviets sent troops to a group of islands known as the Habomai Islands, located off the northeastern side of Hokkaido, Japan’s northernmost Home Island. The Blue arrow points to Hokkaido, Japan. Note the location of Nemuro, Japan, in Hokkaido. The red box encompasses the Habomai Islands, which the Soviet Union claimed after WWII. The Russians continue to claim these Islands as theirs. The Suisho, Akiyuri, and Yuri islands apply to this RB-29 story. The US claimed that the Habomai Islands “rightfully” belonged to Japan. However, the reality at the time was that the Soviet Union annexed them following WWII.

Nemuro is located on the Nemuro Peninsula, a section of Hokkaido. A US-Japanese radar facility at Nemuro tracked the RB-29.

The second reason I find this story compelling is the geography of this area. The RB-29 was flying over the Nemuro Peninsula. Navigating this area without violating Soviet airspace was a challenge.

Michael L. Peterson wrote a story entitled “Maybe You Had to Be There,” published by Cryptology Quarterly. Peterson was the Center for Cryptologic History historian at the National Security Agency (NSA). The report has been declassified.

Peterson said Communications Intelligence (COMINT) intercepts of Soviet tracking were “sketchy.” The Soviets tracked the RB-29 starting about an hour before the shootdown. There were no COMINT intercepts of the Soviets tracking the fighters; the Nemuro radar did detect “aircraft coming from the direction of the Kuriles about twenty minutes before the (shootdown).

Peterson mapped out the locations of the RB-29 as reflected by a Soviet air defense tracking station on Kunashiri Island northeast of the Nemuro Peninsula. In other words, a US Signal Intelligence (SIGINT) site intercepted Soviet tracking of the RB-29. I have roughed out a diagram showing where Soviet tracking said the RB-29 was using a blue arrow line. The blue dot is the rough area between Suisho and Yuri Islands where the RB-29 crashed. The blue square shows the last position reported by the Nemuro Radar.

Peterson said the Nemuro facility warned the RB-29 of the other aircraft. In response, the crew said they had spotted the aircraft but chose to continue in the area for about another hour. About thirteen minutes later, the Soviets tracked the RB-29, heading east.

At this point, the “RB-29 sent a well-known distress message: ‘Mayday! Let’s get the hell out of here!’” The Soviets also tracked USAF F-84 fighters that had been sent to assist the RB-29 and also tracked Allied rescue aircraft for another three hours after the shootdown.

On March 14, 1956, the US submitted a formal charge against the Soviet Union to the International Court of Justice (ICJ) regarding this shootdown.

The US diplomatic claim asserts the “B-29 passed the end of Nemuro Peninsula of the Island of Hokkaido and began a turn westward to fly farther into the mainland of Hokkaido.” It further asserts the Soviet fighters “were located in the air space of Hokkaido approximately thirty-two miles west of Yuri Island and six miles north of Nemuro Peninsula over the territorial waters of the island of Hokkaido.” I have drawn a circle with a 32-mile radius from Yuri Island. Saying the RB-29 turned westward does not match Soviet tracking or Nemuro’s last known location.

The charging document claims the Soviet fighters overflew the Nemuro Peninsula, flew on a track that merged with the RB-29, flew above the RB-29, and then dove to get behind it, at which point the two Soviet fighters shot it down.

The charging document, submitted four years after the shootdown, provides an informative summation of events,

“The Government of the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics on October 7, 1952, willfully and unlawfully caused fighter aircraft to overfly the territory of Japan, to hover over and pace a United States Air Force B-29 aircraft lawfully flying over Japan, the Soviet aircraft doing so unbeknown to the crew of the United States Air Force B-29, and without any provocation to attack and destroy the United States Air Force B-29, causing it to crash into the sea at a point between Yuri Island and Akiyuri Island in territory rightfully belonging to Japan; that the crew of eight, all members of the United States Air Force and nationals of the United States, have failed to return; and that the Soviet Government has concealed from the United States Government information as to the fate of the crew and has not made provision for the prompt return of any crew members whom it may still be holding or of whose whereabouts it is informed.”

Note the US called Sunbonnet a B-29 rather than an RB-29.

The charging documents continued,

“The Soviets sent two fighter aircraft to intercept the B-29 over Japanese territory. The two fighters flew in a course to converge with the course of the B-29 and to intercept it.

“These Soviet authorities had not notified traffic control authorities in Japan, and the fighters were not authorized to overfly Japan. At 2:45 pm local time, the two Soviet fighter aircraft were located in the air space of Hokkaido, approximately thirty-two miles west of Yuri Island and six miles north of Nemuro Peninsula, over the territorial waters of the island of Hokkaido. They flew directly above the B-29’s position such that the B-29 crew could not see them. The Soviet fighters were controlled by Soviet authorities and paced the B-29 from 2:15 pm to 2:31 p.m. local time.

“The fighters dove from their high altitude flew behind the B-29, and without warning opened fire. They hit the B-29, and it plunged to the sea between Yuri Island and Akiyuri Island, southwest of Harukarimoshiri Island, all in territory rightfully belonging to Japan. The aircraft exploded and floated as wreckage upon the surface of the water.

“The B-29 crew called out on voice radio on an international emergency channel that they were in extreme distress and attempted to abandon the plane in the air. The US concluded that some or all of the crew of the B-29 successfully parachuted to the sea.”

This last statement suggests members of the crew might have survived, implying the Soviets captured them and were holding them.

A third reason this story has intrigued me is related to Capt. John R. “Chute” Dunham, USAF, the navigator. He was a photographic navigator, and the mission was said to be a photo mapping mission of Hokkaido. He was also a graduate of the US Naval Academy.

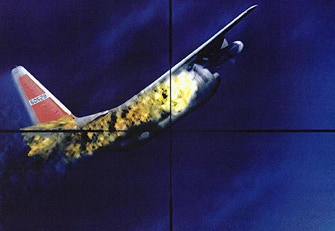

The Cryptology Information Warfare website said one La-11 canon hit the RB-29 in the left wing, and the other La-11 struck her in the tail. The article went on to say,

“Emitting flames and black smoke, the crippled aircraft nosed hard left and began a downward spiral. Four miles below, Vasily Saiko, a 24-year-old sergeant in the Soviet Maritime Border Guards, stood on the deck of his patrol vessel, watching the grim ballet above. Seconds later, the Sunbonnet King crashed and exploded in Soviet waters near the tiny Japanese island of Yuri.

“Saiko and the two other Soviet sailors were ordered to take a small boat and begin collecting what debris they could find. The waves were choppy, and from their vantage point little was visible except gas and oil floating on the surface and a rubber tire bobbing aimlessly amid the flotsam. Suddenly the men spotted a partially submerged parachute. Attached to its cords was a man floating face down in the oily, dark waters. ‘He might be alive!’ Saiko shouted.

“The three sailors managed to pull the American into the boat only to make a gruesome discovery: the front and top of the airman’s head had been sheared off, leaving no vestige of a face. The men grimaced and looked away. Solemnly they returned to the patrol vessel, where the American’s body was wrapped in a tarpaulin and stowed.”

The Snowden and Warfield family genealogy website posted an article from the February 1996 issue of Reader’s Digest entitled “Ring of Truth.” This article said that Saiko was instructed to go to Yuri Island and wait for it (Dunham’s body) to be picked up for examination and burial.”

Before the detail arrived, “Saiko pulled the tarp away. On the man's right (hand) was the most extraordinary ring he had ever seen. Large and heavy, it seemed to be made of the purest gold.”

It was Dunham’s graduate ring from the US Naval Academy. Saiko took it off Dunham’s hand, showed it to the other crewmembers of his boat, and hid it.

In 1993, Saiko voluntarily met with members of the Joint Russia-US Commission on POW-MIA Affairs in Moscow, told his story, and returned the ring.

It appears that Capt. Dunham’s remains were buried in a coffin in a former Japanese cemetery on the Russian-controlled Kurile island, possibly Yuri Island. His remains were returned in 1993-1994. He was buried at Arlington National Cemetery on August 1, 1995.

This is quite a story. Here is yet another curious account.

A Morning Call Staff Report of November 12, 1995, said that Robert Robitaille was a tail gunner on one of the B-29 search planes that looked for the Sunbonnet. Robitaille said he saw a B-29 “high in the water” and two life rafts almost 20 hours after Sunbonnet went down. He said he tried to tell his mission commander but “could not get (him to listen).” Robitaille is quoted saying,

“The (Sunbonnet) aircraft seemed high in the water, and as soon as I reported it, the aircraft commander put the plane into a high left bank, and I couldn’t see it anymore.” He added that another gunner also saw it and the mission commander returned to the scene. They could not see any wreckage.

However, Robitaille said that what they did see was the wake of a submarine heading toward Vladivostok. He said the officers were debriefed after their flight, but the enlisted men were never questioned.

I wonder whether the wake he saw was that of Saiko’s boat.

The US complaint to the ICJ included the “Saiko story.” It said,

“Within a few minutes thereafter, and while the wrecked aircraft and its crew were still on the surface of the sea, a patrol boat belonging to the Soviet Government. upon orders of competent Soviet authorities, left the Island of Suisho, east of the Nosappu Lighthouse and northwest of the position where the B-29 was shot and came down, and proceeded to the scene of the wreckage. The United States Government concludes, and therefore charges, that this was for the purpose of picking up survivors and objects in the debris of the aircraft of possible interest to the Soviet Government.

“Undoubtedly having accomplished its mission the patrol boat then retumed to Suisho Island. The United States Government concludes, and charges, that the Soviet Government's patrol boat

did pick up items of interest to the Soviet Government as well as survivors still alive and bodies of other crew members, if dead.”

The Soviets said they tracked USAF F-84 fighters to assist the RB-29 before it was shot down, and the Soviets also tracked rescue aircraft responding to the crash. However, the USAF said there were no other US aircraft in the area at the time of the shootdown.

About an hour before the shootdown, the RB-29 was tracked over Hokkaido airspace. The Air Force said she was at 15,000 ft. altitude. About 13 minutes later, the RB-29 began heading east toward an area claimed by the Soviets to be their airspace. The USAF said another aircraft was approaching the RB-29, heading westerly toward her. The Air Force said the radar tracks of the two planes merged about eight miles northwest of Nemuro, which was inside Japanese territorial airspace. The merged tracks continued overflying Japanese airspace to the southeast, disappearing from the radar scope. It is presumed the intruding aircraft was Soviet and that after it shot down the RB-29, it dove below radar coverage, which would explain why they both disappeared from radar coverage.

The US and Soviets searched for the wreckage to no avail. Dr. Robert D. Eldridge reported,

“The Soviet pilot, who was serving as the Deputy Commander of the 368th Fighter Air Regiment in southern Sakhalin Island … told interviewers later the U.S. ‘plane blew up in the air at 5000 meters (16,400 ft), with the wings separating from the fuselage before it crashed into the sea near the shore...no air crewman could have survived the shootdown.’

“The Soviet pilot added that after intercepting the RB-29 south of Harukaru (or Demina) Island, he ‘warned the plane and tried to get it to land. When [my] warnings were ignored, [I] fired at it.’ The body of First Lieutenant John R. Dunham was transported to Yuri, an uninhabited island which previously supported a population of more than 500 Japanese who had been mostly engaged in commercial fishing. Dunham, the flight navigator, was buried there on October 10.”

The F-16.net website said the Soviet pilots were Alekseyevich Zhiryakov and Leonov.

__________

Go to USAF RB-50, Sea of Japan, July 29, 1953

Click to zoom graphic-photo

Table of Contents

- Introduction

- USN PB4Y2, Baltic Sea, April 8, 1950

- USN P2V Neptune, Sea of Japan, November 6, 1951

- USAF RB-29, June 13, Sea of Japan, June 13, 1952

- USAF RB-29, Sea of Japan, October 7, 1952

- USAF RB-50, Sea of Japan, July 29, 1953

- USN P2V, Sea of Japan, September 4, 1954

- USAF RB-29A , Sea of Japan, November 7, 1954

- USAF RB-47 , off-shore Kamchatka Peninsula, April 18, 1955

- USAF RB-50G , Sea of Japan, September 10, 1956

- USAF C-130A , Soviet Armenia, September 2, 1958

- USAF RB-47H , Barents Sea, July 1, 1960

- USAF RB-66C , East Germany, March 10, 1964