DUTY, HONOR, COURAGE, RESILIANCE

Talking Proud: Service & Sacrifice

Airborne Peripheral Reconnaissance, Cold War Losses

“Silent Sacrifices”

USN PB4Y2 Privateer, Baltic Sea, April 8, 1950

In response to national policy, the Navy began a highly secretive program in 1950 or perhaps 1949 known as the Special Electronic Search Project (SESP). This program was designed to equip particular aircraft with Signals Intelligence (SIGINT) equipment and operate them with SIGINT-trained crews. The Naval Security Group (NSG) provided SIGINT personnel to operate the intercept equipment aboard Navy aircraft.

The PB4Y2 was a good candidate for this mission. The SIGINT intercept equipment in those days was of the “vacuum tube” variety, bulky and heavy. This aircraft provided an extended dwell time capability.

On April 8, 1950, four Soviet La-11 fighters shot down a USN PB4Y2 over the Baltic Sea southwest of Liepaja, Latvia.

This PB4Y2, named “Turbulent Turtle,” was home-based in Port Lyautey, French Morocco, shown here. Seven days before this flight over the Baltic, it left French Morocco for Wiesbaden, West Germany. It was assigned to Patrol Squadron 26 (VP-26). NSG Station Port Lyautey members were aboard (NCU-32, Det A).

The VP-26 aircraft departed from Wiesbaden at 10:31 local time on April 8, 1950. The crew reported flying over Bremerhaven, West Germany, in the north and sent its last radio report about four hours and ten minutes after launch. Nine hours later, the USAF Flight Service at Frankfurt reported her overdue. A major Search and Rescue operation began immediately, employing Navy and USAF aircraft. That effort terminated on April 11, 1950.

According to Michael L. Peterson in his report “Maybe You Had to be There: The SIGINT in Thirteen Soviet Shootdowns of US Reconnaissance Aircraft,” US intercepts of Soviet tracking were sparse. This map reflects an approximation of where the Soviets said the Navy aircraft was between 1221Z and 1441Z when it was lost in tracking. The ground intercept stations could only tentatively correlate the cessation of tracking on the PB4Y2 with being shot down.

Four Soviet La-11 fighters piloted by Boris Dokin, Anatoliy Gerasimov, Tezyaev, and Sataev intercepted the PB4Y2 “Privateer” (BuNo 59645), “Turbulent Turtle,” over the Baltic Sea near Liepaja. During WWII, the Soviets occupied Latvia. They incorporated it into the Soviet Union after the war. The Privateer was flying at 12,139 ft, 8 km southwest of Liepaja, Latvia.

The Soviets tracked up to five fighters flying for about 45 minutes, but the tracking was continuous for only one of the fighters. I have seen reports saying the PB4Y2 came as close as 8 and 16 km to 40 km from the Latvian coastline. The Soviets claimed the aircraft was 21 km over Latvia. The US maintained she was operating over the high seas in international waters.

Some reports say the Soviets gave the Navy pilots the “follow me” signal and the Soviet flight leader reported that the USN pilot waved goodbye. As a result, the Soviet controller told the pilot to shoot it down. At least one Soviet pilot did that off the coast of Liepaja, Latvia.

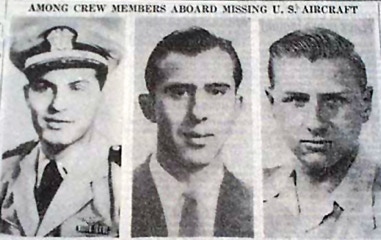

Ten souls were aboard, all lost. Their remains were never recovered. The crew included Lt. John Fette (photo middle), Lt. Howard Seeschaf (photo right), Lt j.g. Robert Reynolds, Ensign Tommy Burgess (photo left), AD1 Joe Danens, Jr., AD1 Jack Thomas, AT1 Frank Beckman, CT3 Edward Purcell (lower photo), AL3 Joseph Bourassa, AT3 Joseph Rinnier, Jr. I believe Fette was the pilot.

The Soviets acknowledged shooting down the PB4. The Soviet Foreign Ministry said it was in Soviet airspace. It also said the USN aircraft had fired on Soviet fighters. The PB4 did have .50 in—M2 Browning machine guns.

The US said the PB4 was on a training mission from Germany to Denmark but acknowledged in 1975 that it was engaged in a “special electronic search project mission.”

According to interviews with the Soviets long after this engagement, they would have much preferred to get the Navy aircraft to land so they would have the aircraft and the crew. That said, the Soviet attacking pilots were told not to harm any survivors and to circle them until submarines or other boats could get there to retrieve them. This is thought to be the first publicized Soviet shootdown of a US reconnaissance aircraft.

One of the Soviet pilots involved, Anatolij Gerassimov, has said he saw the US aircraft burning in the middle, then he said he saw ten parachutes, and then the aircraft exploded. However, General Colonel Fedor Ivanovich Shinkarenko later said Soviet pilots did not see the PB4 go down because of cloud cover. He said,

“All pilots of the plane died…it’s sad, we had no confirmation that we have found the bodies…they were washed away … If there had been one member of the crew, dead or alive after the search was carried out … I should have known this…”

The Baltic Sea was a hotbed of intelligence gathering in the early Cold War years. The Baltic States, Lithuania, Latvia, and Estonia, were among the most heavily fortified Soviet areas in the world. That attracted a great deal of reconnaissance attention. Airborne SIGINT reconnaissance could hear into the USSR, Poland, and East Germany.

Gerassimov has been quoted as saying many US flights were in this area dropping material and agents for the “forest brother,” Lithuanian guerrillas fighting the Soviets at the time. He also said the Soviets lost many pilots chasing after these aircraft because of bad weather. The pilots lobbied hard to either shoot down the US aircraft or not go after them at all.

Paul Crenshaw, writing “Secret Casualties of the Cold War” for Smithsonian Magazine, reported that James Connell worked in the Soviet Union back then and examined the archives made available to him. Crenshaw wrote that Connell “learned that Soviet rescue vessels were at the site of the Privateer’s crash within hours. While they didn’t find any aircraft wreckage, they did discover two inflated life rafts.”

John R. Schindler, writing “A dangerous business: The US Navy and National Reconnaissance during the Cold War,” published by the National Security Agency (NSA), said the US recovered some of the wreckage and described the wreckage as “bullet-ridden.”

Commercial fishing vessels recovered two unmanned life rafts. Lt. Commander Malcolm W. Cagle, USN, writing for the US Naval Institute, reported details about this loss. I commend his report.

Cagle said a British freighter, Beechland, found a yellow raft with USN markings, partially inflated and in good condition. Five days later, a small Swedish ship, the Hillade, found a second raft, which was not inflated. Yet another Swedish ship fishing for salmon found a nosewheel assembly with “PB4Y-2” stamped on the main strut. The Navy said each raft could carry seven men and be dropped from the air.

There have been many unconfirmed reports of sightings of Navy rafts with people in them, and there have even been reports that the aircraft and some crew were taken to Moscow, the crew subsequently imprisoned. Other Soviets have said they secretly salvaged the aircraft and brought it to Moscow. To my knowledge, no one in the public domain is sure.

The loss of the PB4 did create a diplomatic stir. Cagle noted The Soviets sent the following to the US,

“The Government of the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics deems it necessary to state to the Government of the United States the following:

“According to verified data, on 8 April of this year, at 17 hours and 39 minutes (5:39 Moscow time: this would be 2:39 p.m. in relation to the plane’s take-off time) south of Libau, Latvia, a four engined military plane of the B-29 type bearing American identification marks was sighted. The plane penetrated the territory of the Soviet Union to a distance of 21 kilometers (thirteen miles).

“Owing to the fact that the American plane continued to penetrate into Soviet territory, a flight of Soviet fighters took off from a nearby airdrome and demanded that the American plane follow it and land at the airdrome. The American plane not only failed to comply with this demand but opened fire on the Soviet planes.

Alan G. Kirk, US Ambassador to Russia, met with Soviet Deputy Foreign Minister Gromyko on April 18, 1950, to deliver a US protest. More notes were exchanged later.

The website Cryptology Information Warfare reported that in 1956, the US State Department sent a demarche (statement) to the Soviet government that said,

“The demarche specifically referred to reports from persons formerly detained in the Soviet Union that they had ‘conversed with, seen, or heard reports concerning United States military aviation,’ in the Gulag, and concluded that the United States government ‘is compelled to believe that the Soviet government has had or continues to have under detention’ members of the Privateer crew.”

The official position of the US Government is said to be that aircrew members of this Navy flight were captured and held in Soviet Gulags until their deaths.

The Soviet La-11 entered production in 1947 and ended in 1951, with about 1,182 being built. She was a long-range piston-engine fighter, and she was early post-WWII. This engagement with the Navy’s Privateer was the first “combat” engagement for the La-11. She was designed to escort Soviet bombers destined for the US and had wingtip tanks installed for extra fuel. She carried three NS-23 cannons, all in the nose. Her maximum speed was 419 mph, she could operate up to 33,650 ft., and she had a range of 1,585 miles.

Cagle concluded that “the Cold War breach has been widened,” but incidents like this are unlikely to start a war. He opined the incident provided good insights into Soviet tactics: “Lies and falsehoods are standard tools; seize the offensive with a bag full; twist the take and wring it to advantage; prove to the world that Soviet Air Defense is capable of repelling American air power.”

The Rand Corp. published the results of a study it did of “Actual and Alleged Overflights, 1930-1953,” prepared by A. L. George and published in 1955. It has been declassified. The report sheds some light on why the Soviets chose to shoot down this Navy aircraft. George wrote,

“The shooting down of the Navy plane … marked a major turning point in Soviet policy toward air encroachments around the Soviet perimeter. For the first time in the postwar period, the Soviets asserted the right to force foreign planes suspected of violating their territory to land on Soviet territory, and, to shoot them down if they refused to land and attempted instead to return to international airspace.”

My reading of the Rand conclusion is that the Soviets felt US reconnaissance missions around the Soviet perimeter had increased and the Politburo decided to put its foot down.

__________

Click to zoom graphic-photo

Table of Contents

- Introduction

- USN PB4Y2, Baltic Sea, April 8, 1950

- USN P2V Neptune, Sea of Japan, November 6, 1951

- USAF RB-29, June 13, Sea of Japan, June 13, 1952

- USAF RB-29, Sea of Japan, October 7, 1952

- USAF RB-50, Sea of Japan, July 29, 1953

- USN P2V, Sea of Japan, September 4, 1954

- USAF RB-29A , Sea of Japan, November 7, 1954

- USAF RB-47 , off-shore Kamchatka Peninsula, April 18, 1955

- USAF RB-50G , Sea of Japan, September 10, 1956

- USAF C-130A , Soviet Armenia, September 2, 1958

- USAF RB-47H , Barents Sea, July 1, 1960

- USAF RB-66C , East Germany, March 10, 1964