DUTY, HONOR, COURAGE, RESILIANCE

Talking Proud: Service & Sacrifice

Part 2: Sczubin to Moosburg

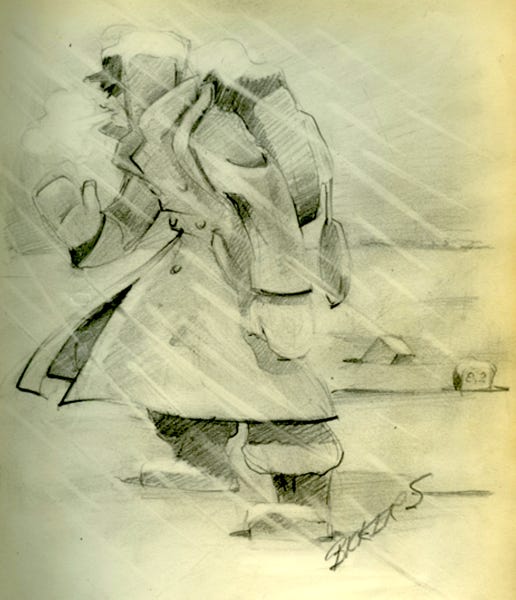

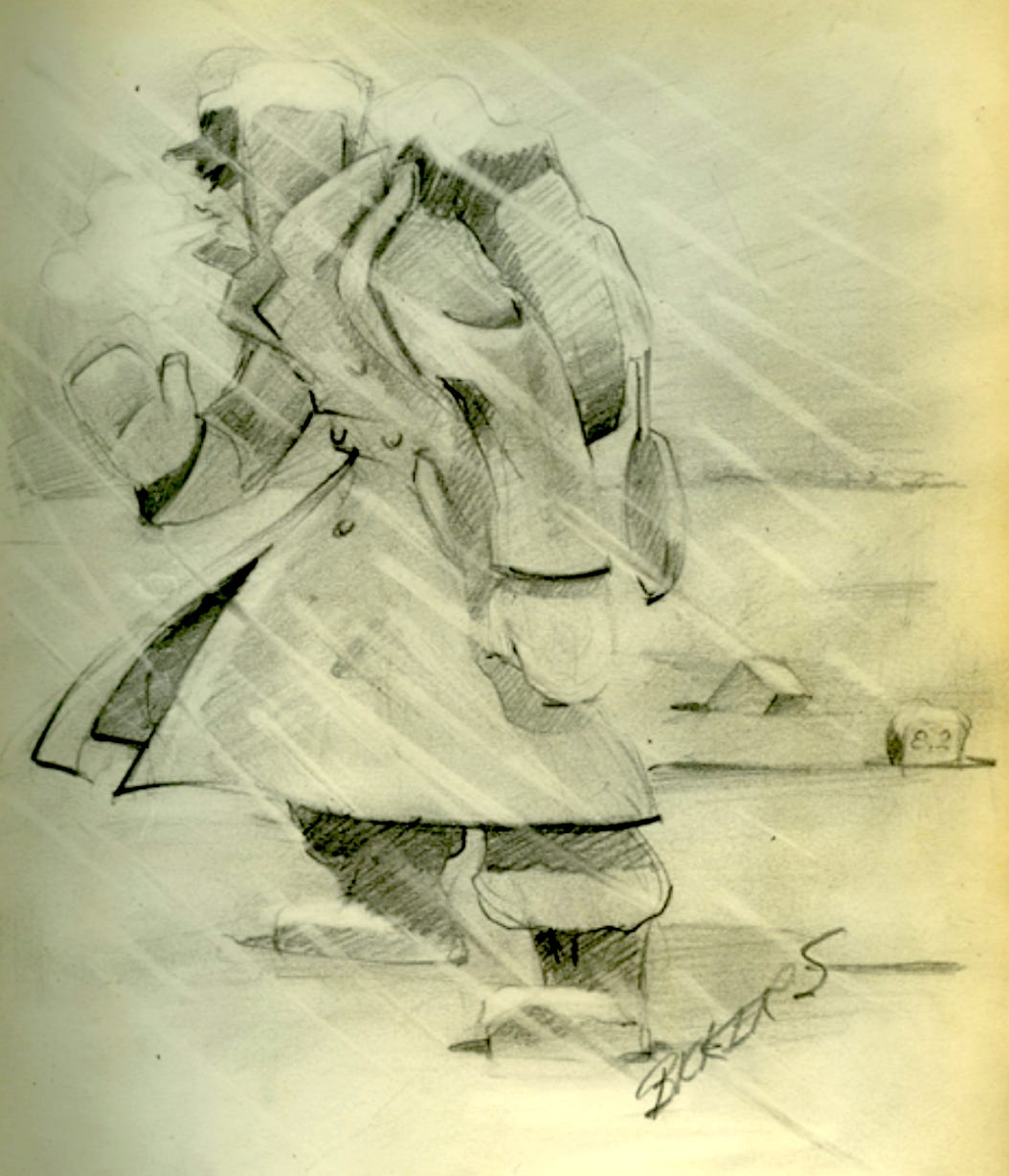

Graphic by Lt. James F. Bickers, USA, POW Oflag 64

Let’s now switch to the men of Oflag 64, who made the long march from Sczubin, Poland, to Moosburg in southern Bavaria, near Munich and the border with Austria.

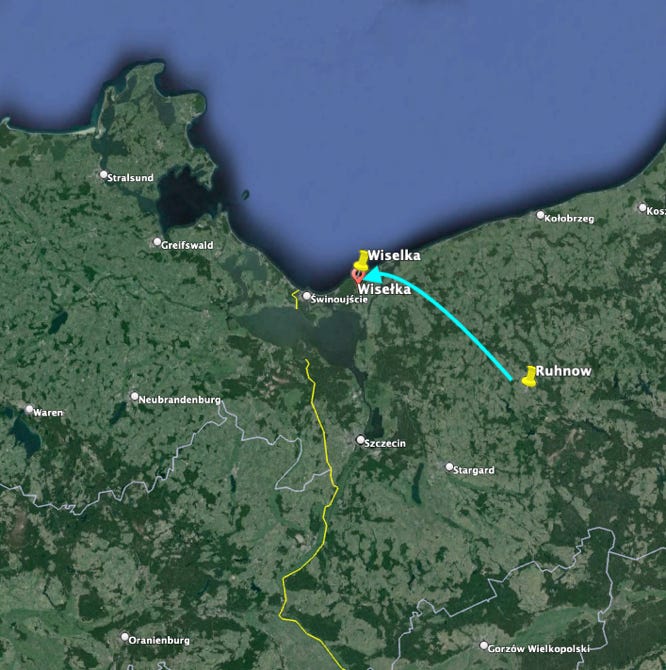

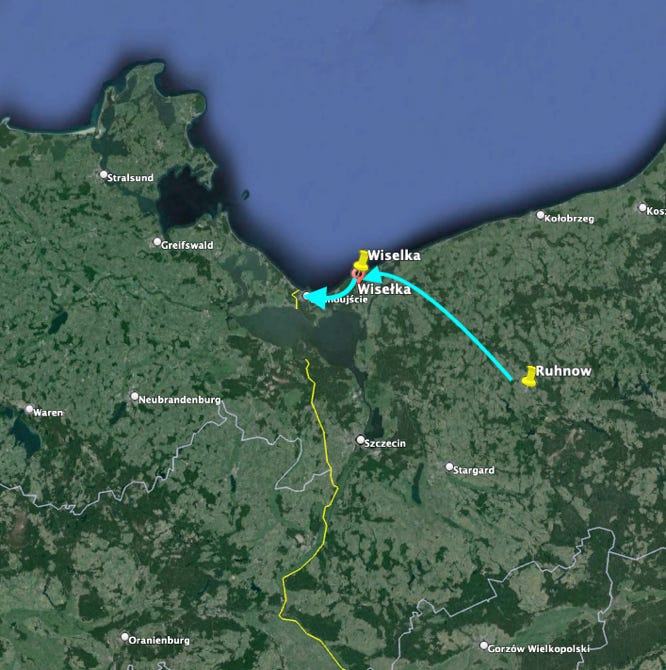

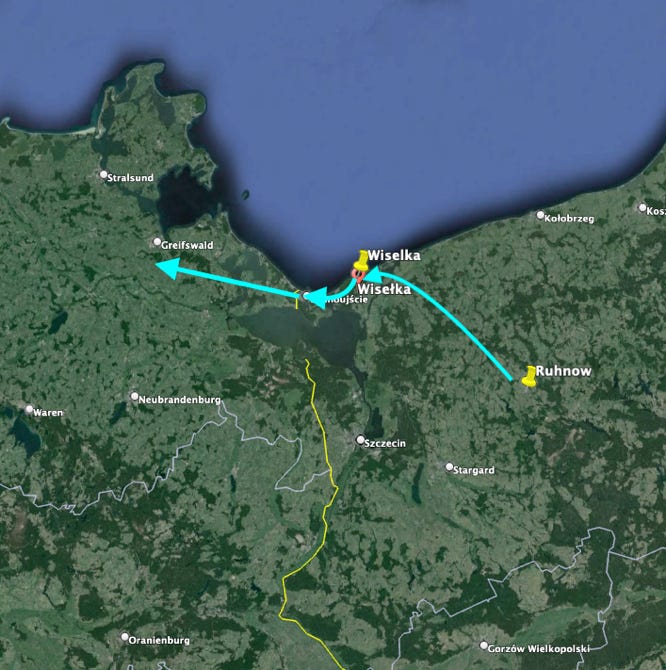

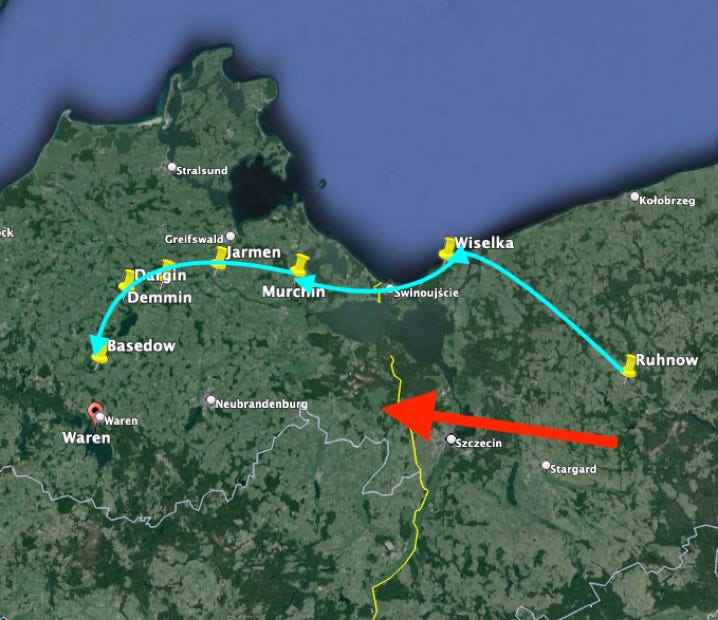

Recall that on or about February 5, 1945, the Oflag 64 column broke into at least two sections near Ruhnow in northwest Poland, where there was a train station. One group went to Luckenwalde, Stalag III-A, south-southwest of Berlin, and the other to Moosburg, Stalag VII-A.

Lt. Kanners said about 550 officers were left in the group that continued on the march. Capt. Watts estimated 450.

Kanners did not go to Luckenwalde, mainly because he refused to go on a train. He recalled that all he could hear was bombs detonating from inside the boxcar during the eight-day train trip that brought him to Szcubin. He said, "No sir, no train rides. I'll keep walking."

I’m not sure if the marching POWs knew they were so close to the Baltic Sea until they got there. Kanners said they were getting into a marching rhythm,

“Our days have been pretty well regulated lately. We take ten minute breaks every hour while marching, and thirty minutes at noon. Our pace is about 2-1/4 to 2-1/2 miles an hour. The deep snow is past us although it is still wet and plenty damp. We still look forward daily to our ONE consolation - the sack. That they can’t take away from us. No matter how miserable the day, no matter how thin the soup - our sack, that we have in all its glory.”

From February 8 to 11, they marched through towns along the Baltic Sea and crossed a branch of the Oder River called the Dzwina River. They then crossed Wolin Island to Neuendorf (Wiselka), arriving on February 11.

During this march, Lt. Sandford said they saw Russian, British, and Canadian POWs "herded along the road at a fast pace, guards beating them with rifle butts, (a) forlorn sight." Sandford commented that the land here was "scenic tourist country, neat, trim cottages, town chock full of children of the Goering Home for Children - stayed in barracks at the airport for seaplanes on the island - air school with many singing marching youths in attendance."

On February 12, they arrived at Swinemuende (Swinoujscie), home to a significant German naval base. The men got to sleep on barracks floors; they had heat and got some food. Lt. Dr. Graffagnino described this part of the march,

“We had survived a two-week march across northern Poland in howling blizzards and temperatures of 20 and 30 below.”

Swinemunde was experiencing a major influx of Polish refugees fleeing the advancing Soviet Army. The Poles were yet again in a very tough position. The Germans and the Soviets had occupied them, then just the Germans, and were now being overrun by the Soviets. Many chose to head to Germany rather than remain in Poland. Many who remained in Poland were murdered by the Soviets or shipped to Gulags in Siberia.

Sometime during this period, February 12- 15, the Oflag 64 marching column had to leave about 150 men behind who could not continue. Dr. Graffagnino and Lt. Col. David Gold, 101st Airborne, were the two doctors left with the column group. Gold decided that Graffagnino should stay with the 150 POWs at Swinemunde, as the Germans promised to move them by rail. Gold went on marching with the rest.

In the previous section, a group was left up in this area, put on trains at nearby Usedom, and taken to Stalag III-A at Luckenwalde. I believe this was that group. Graffagnino was with them and ended up in Luckenwalde.

The remaining Oflag 64 POWs went to Gorze (Garz), arriving on February 13. At Garz, they were separated into groups of 50. They then went to Stolpe on February 14, where they stayed for an extra day. Over the past days, the men had gotten some food, mostly potatoes, and they found Germans willing to give them a few cigarettes.

On February 15, they left for Murchin. Sandford said they were told they were going to Stalag IB but did not; it was at Hohenstein, a bit to the south. Instead, they arrived at Murchin. They crossed a bridge outfitted with demolition bombs. This is the first day Sandford reported having gastrointestinal (GI) problems. On February 17, they traveled to Jarmen, where they observed German youth engaged in glider contests and having fun while the Soviets were advancing into Germany.

The POWs remained overnight at Jarmen. Sandford reported they stayed on the estate of a German countess whose son had been captured by the Americans and was in a POW camp in the States. The POWs assured her that her son was fine. She persuaded German Oberst Schneider to let them have a day of rest. Sandford reported he still had the GIs. He also said there were now only 490 POWs left, about a third of the original group.

The POWs marched out of Jarmen on February 19 and arrived that same day in or around Demmin, described by Sandford as a large and colorful city. Once they stopped, Oberst Schneider told the POWs their march was almost over, two more days at most.

Schneider also announced (he was fond of making announcements) that he would be catching a train out within a few days and told the prisoners that after failing to get permission for more Red Cross supplies, he commandeered some intended for the Canadians and would give them to the Americans. The POWs received some Canadian boxes and even got coffee from the wagon.

They marched to Dargin on February 20 and stayed a second night, February 21. By February 21, the POWs were making their own varieties of food, using the potatoes given them to make french fries, creamed potatoes, mashed potatoes, and even au gratin.

The POWs pressed on to Basedow on February 23. They saw American soldiers working on a damaged rail line. As you can see from this map, the column had now taken a marked turn to the south. The Kriegies were well inside Germany and heading southward.

By this time, significant units of the Soviet First Ukrainian Army Group had crossed the Oder River into Germany, roughly shown by the red arrow. Units of the First White Russian Army Group had taken Poznan to the southeast and continued moving westward. The Second White Russian Army Group had crossed the Vistula farther north and was headed northward to the Baltic. East Prussia was in the hands of First and Second White Russian Army Group units.

The POWs proceeded on February 24 to Cramon and Plauerhagen to the southwest, where they got another day of rest on February 26. During their march to Plauerhagen, Sandford said workers would sneak out and give the POWs food, and the guards would chase after them. The workers would duck into houses and barns, grab some more food, and sneak it back to the POWs, with the guards chasing them in and out of doors. Sandford described it as a "Merry Go Round." Sandford called them "arbeiters", meaning "workers," so I’m unsure of their nationality.

After they hit the Baltic Sea, the POW march continued, maintaining a westerly and southwesterly direction. On February 7, they arrived at Lutheran, where Sandford reported French workers were on a small farm, and they bartered with food and coffee.

Their march to and arrival at Siggelkow on February 28 would begin a significant turn of events. Understandably, the Germans are marching the Oflag 64 column to the southwest. The Russians are coming, so they are being marched to the south, hoping to get as close to Austria as possible and to the west to escape the Russian advance.

Sandford said they walked a "circuitous route across the country in a long 'shortcut' in sight of Parchim," a reasonably large city just a tad to the northwest of Siggelkow. They heard air raid sirens from that direction.

Sandford added that they were greeted by a "'Welcoming' group in top hats and tails." The owner of the land on which they stayed gave them firewood, and they got huge loaves of bread from a local bakery. While conditions were never good for the Oflag 64 men, the farther they moved into Germany, the better the food and the better the hospitality of the German people.

The POWs were then told they would remain at Siggelkow until a train was ready. They waited nearly a week until March 6 and were marched to Parchim, where a train was waiting, miraculously marked "US POW" on the roofs. Lt. Corbin said they stayed there for a couple of days and rested.

In February 1945, the Soviets had begun their invasion into Eastern Germany and, by March, were in striking distance of Berlin.

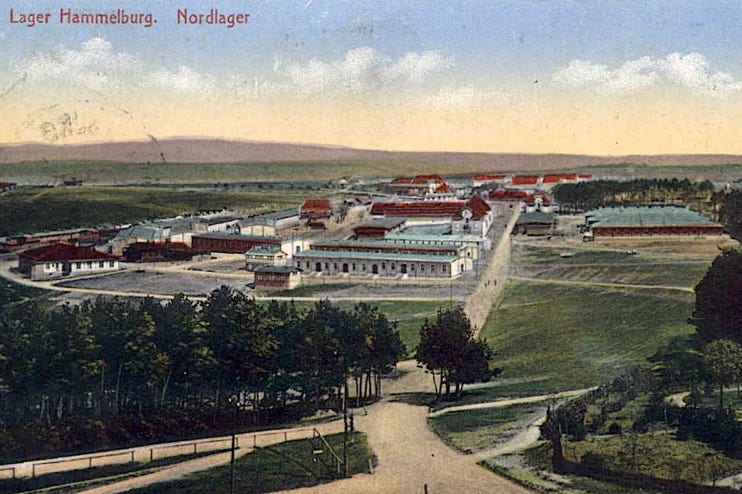

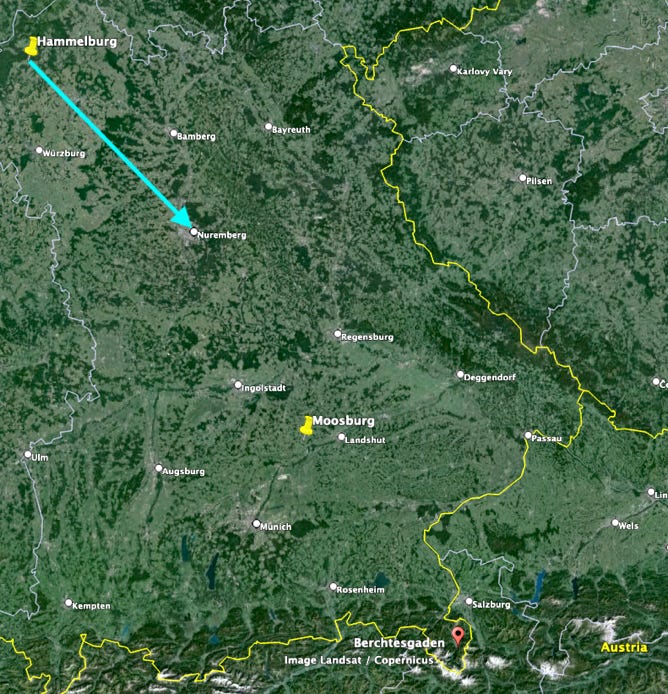

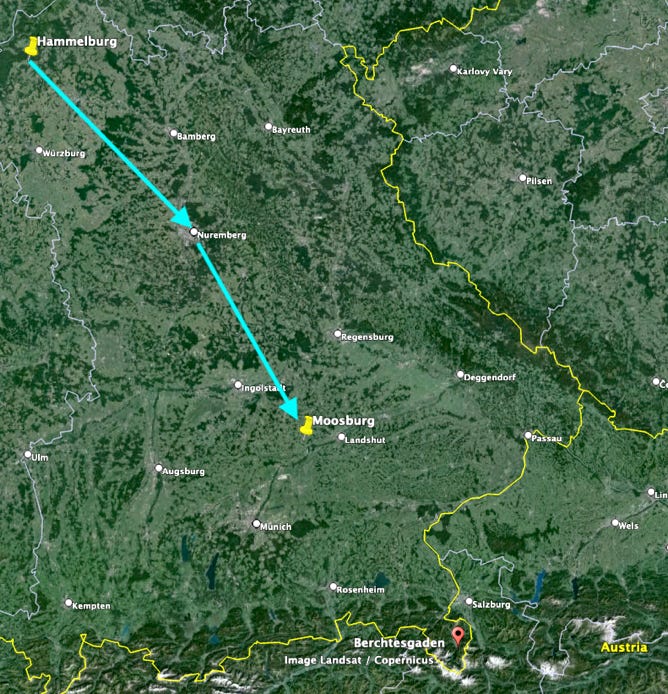

I’m unsure whether the POWs knew where they were going, but they were heading south to Hammelburg, home of Oflag XIII-B. For the Germans, the marching column was too slow. The Soviets were zeroing in on Berlin. The Germans had to get their POWs to the south in a hurry, so they moved the Oflag 64 marchers by train to Hammelburg.

Lt. James Cockrell, captured in North Africa, said an estimated 400 POWs made the trip to Hammelburg. He commented, “Almost every night (during the long march), some of the prisoners would be left because they could not walk further or had hidden somewhere and were not found. As a result, our numbers gradually reduced.”

The train trip to the Hammelburg area took two days (March 7-8), and then they walked to their new prison, arriving on March 10.

Life changed dramatically, and so did events on the ground. Lt. Corbin said,

“When we arrived at Hammelburg (Oflag XIII-B), conditions were very poor, the food was terrible, we had lice, a terrible situation … In discussing the lice, I can’t tell you what a horrible feeling it is to feel a creature crawling across your skin. Every night before we turned out the light and went to bed, everybody would take off their GI underwear and turn it inside out, and go through and pick off all the lice they could find.”

Lt. Kanners remarked on the lice, saying,

“The lice would stay in the seams of our clothing to keep warm while we marched. But when we hit the sack where it was warm they would come out for a little stroll. They caused no infection or disease, but managed to irritate the hell out of you.”

Lt. Drake mentioned they were deloused at Hammelburg and then searched. He managed to sneak in a compass, which he hid in the bowl of his pipe, packed with tobacco.

Oflag XIII-B was populated mostly by officers captured during the Battle of the Bulge, which began on December 16, 1944, and extended through January 7, 1945.

Twenty-three thousand American troops were captured during that battle. The Germans executed many, the more infamous executions known as the Maledy Massacres, where German SS Kampfgruppe Peiper murdered at least 84 unarmed American prisoners. The Germans moved prisoners to various camps, Oflag XIII-B being one of them.

Lt. Herndon Inge, Jr., 101st Airborne, captured at the Battle of the Bulge, said he and others from that fight arrived at Oflag XIII-B when the men from Oflag 64 arrived. He estimated there were about 1,500 American officer POWs at Oflag XIII-B once these arrivals were concluded.

This long march from Oflag 64 to Oflag XIII-B at Hammelburg was over. They had marched 357 miles.

Capt. Chesley Russell, 121st Combat Engineers, said this about the march:

“To survive I learned to trade cigarettes for food, steal potatoes and vegetables and even bread, and to keep walking some days on my nerve alone. For the first 48 days, I didn’t take my clothes off once, then I took a bath in a pigpen. Many incidents occurred during this trip which I don’t have time to mention here, but, if you’re interested, I’ll tell you about them sometime.”

Oberst Schneider gave his prisoners a farewell talk, commending them for being good prisoners, and told them they would now be under the command of a general at Oflag XIII-B.

I don't know what the POWs knew of the overall situation regarding the war in Europe other than they knew the Germans were close to defeat. The bulk of the Soviet force moving westward could now advance against Berlin.

Germany made Austria a German province in 1938. Information indicated that Hitler's lieutenants were urging him to take what was left of his Army to Bavaria or Austria, into the mountains, and make a stand. This became known as the German National Redoubt, or "Alpenfestung," Alpine Fortress.

Hitler already maintained a vacation residence in Berchtesgaden, in the Alps, and on the border with Austria. So the Alpenfestung concept had merit, enough merit to cause US Army forces to race into the region to prevent Hitler and his forces from hiding there.

The men of Oflag 64, their colleagues from the Battle of the Bulge, and the others at XIII-B were now in northern Bavaria, at Hammelburg, northwest of the so-called Redoubt area shown by the oval on the map.

Oflag XIII-B's population included hundreds of Serbian prisoners who had been there since the war's early days. The Serbs graciously shared their highly prized Red Cross packages when none arrived for the Americans, a favor returned when the Americans liberated the camp.

Oflag XIII-B had been known as Camp Hammelburg since 1935. It was a German military training area. When WWII kicked off, the Germans used parts of the training area for two POW camps, one for Serbian and the other for American officers. Generalmajor Günther von Goeckel commanded the POW camp, and Oberst Richard Hoppe, a German colonel, commanded the training area.

Col. Goode, the Oflag 64 commander, turned out to be the senior POW officer at XIII-B and took charge. In his report to the War Department, Goode said his relations with the general “were by far the best that he established with any German officer.”

Among his first orders of business was to instruct the XIII-B men to "shave and clean up by morning." Most of the POWs there were new to the "Kriegie" business, many from the Battle of the Bulge, while Goode and his men were now the veterans, many from the Battle of Tunisia. They helped the new guys organize, reinvigorate their discipline, and prepare for liberation.

You might wonder why there is a need for such discipline. Air Commodore Len Birchall, Royal Canadian Air Force and a POW of the Japanese for four years, in a riveting speech about leadership, has echoed the words of British Field Marshal Slim when talking about the importance of discipline:

"At some stage and in some circumstances, armies have let their discipline sag, but they have never won victory until they have made it taut again, nor will they. We have found it a great mistake to belittle the importance of smartness in turn-out alertness or carriage, cleanliness of person, saluting or precision of movement, and to dismiss them as naive, unintelligent, parade-ground stuff."

Hammelburg is a well-known spot in WWII POW stories. Lt. Col. John K. Waters, 1st Armor, was married to General Patton’s daughter. He had been at Oflag 64 and was highly respected by the other POWs. He marched with the column to Hammelburg. Patton knew POWs were being held there, and it has been argued he thought Waters might be there. Some say he knew he was there.

Whatever the case, a task force from Patton’s 3rd Army was tasked to get to the POWs at Hammelburg before the Germans shipped them out. Capt. Abraham Baum led the task force named Task Force (TF) Baum. Some might say this TF’s mission was insignificant. Insignificant or not, a great deal has been written about it, primarily because of beliefs Patton ordered the task force to get to the prisoners, namely his son-in-law, and partly because the task force’s mission turned into a military disaster, to some a black mark on Patton’s record.

TF Baum set out on its mission on March 26, 1945, to liberate the POWs at Oflag XIII-B. Its problem was that it did not have a very good plan.

TF Baum met resistance from the outset but forged ahead about three hours behind schedule. About halfway to Hammelburg, there was more resistance and more fierce opposition. Baum was wounded; he lost several tanks and later lost even more vehicles. The Germans called for reinforcements.

Eric Niderost noted,

“As Task Force Baum raced into the unknown, the POWs inside Oflag XIII-B rose to face another day. The POWs at Oflag XIII-B had returned to their normal POW life.”

Capt. Thomas Green, in his research study, “The Hammelburg Raid Revisited,” wrote,

“Major General von Goeckel, the camp commander, notified Col. Goode on March 27 that the POWs should prepare to move the next day. The prison chaplain began his daily service.”

That makes sense. General Patton’s Third Army had crossed the Rhine River into Germany on March 22, 1945. General von Goeckel might have learned about TF Baum as well.

While at church on March 27, the POWs heard tank fire in the town of Hammelburg, and small arms fire was everywhere around the camp.

Lt. Kanners said, “A Sherman tank from the Fourth Armored Division appeared over the horizon and broke any doubt we had as to the proximity of the Americans. The camp was the scene of wild joy.”

Lt. Robert P. Fleege, 73rd Field Artillery, was at the Catholic mass in the barracks when machinegun fire “started to peel some plaster off the adjacent walls. It was every man for himself.” They got word that everyone was to remain in the barracks. Then, all went quiet.

TF Baum finally broke through German lines, and Sherman tanks “crashed through the fences at Oflag XIII.”

Fleege looked out the window and saw Lt. Col. Waters and Hauptmann (Capt.) Fuchs walking and carrying an American flag and a white flag. It looked like the Germans were surrendering. “A great cheer arose from all the men.”

Col. Goode said he was initially told the TF had enough transportation to take his 1,291 POWs back. Recall that the Oflag 64 group he had marched out was now about 400 strong. There were many other POWs there as well.

TF Baum was surprised to learn that there were almost 400 Oflag 64 POWs. The TF had lost several vehicles on its way. TF Baum could not transport that many POWs.

Goode formed up the POWs. Fleege said,

“The main show was over. Orders came down that we were to form up. Take all your meager belongings that you can carry. This was the first day we did not get our ration of bread at 4:00 pm.”

Fleege said the POWs, not knowing there were not enough vehicles but having concluded they had been freed, formed up and started marching. Lt. Kanners noted many of the POWs jumped on the tanks,

“The way we piled on the vehicles it must have looked like a parade, but these boys had come to give us a ride, and we were taking it.”

But Hammelburg was still behind German lines. The POWs then found out they were 60 miles from Allied lines. With his men formed up, Col. Goode spoke to his men. He leveled with them and gave the POWs three choices:

• Go with the remainder of the task force back to American lines,

• Remain at the Hammelburg POW camp or

• Hit the timber and try to get to the American lines on your own.

Capt. Green said 57 chose to leave with TF Baum, and about one-third of the POWs decided to remain at the Oflag XIII-B camp. Col. Goode grabbed a piece of white paper in lieu of a white flag and led the POWs down a dirt road back to Oflag XIII-B.

On their way back to the camp, the POWs heard the sounds of major combat in the area of the TF. The Germans had been able to mount a strong attack against TF Baum and surrounded it. Lt. Kanners and some 57 others went with the TF and its tanks. It turned out the Germans had the TF surrounded. Kanners reported,

“(They) opened up on us with several cannons and sent everyone running. The older the Kriegie, the faster he went over the hill into the woods.”

Those with the TF attempted to break out; some made it, some did not, and many were captured.

Kanners said, “During the shelling a tanker and myself elected to get away in one of the vehicles that had not been hit ... We jumped in the half track and got away, about ten yards, when a shell hit us and that was the end of the half track.” He then fled into the woods and managed to hike about 15 miles to the north, where he slept overnight. But he was recaptured.

Lt. William Warthen, 334the Infantry, summed up the tragedy that befell the POWs and TF Baum.

“The camp was temporarily liberated by a 300-man task force (TF Baum)

“We thought we were free, then in hours the task force was stopped, and about half returned to our barracks, and were moved by rail that afternoon to Nuremberg POW Camp. Several hundred tried to hide, move by night, and hopefully reach the American Lines 35 miles away. Nearly all were recaptured, about 12 to 14 made it …

“Those who were recaptured were moved by rail or marched towards Nuremberg Camp. One of these groups with about 130 Kregies was caught near Nuremberg by an American Bomber, and 29 were killed and many of those were injured. Those who had gone by rail to Nuremberg, were marched out 5 or 6 days later, and in the 2nd hour this group was hit by an American dive bomber and 6 were killed.”

On balance, most saw the TF Baum raid as a failure. Those in TF Baum who were not killed were captured, and most of the POWs who got out were returned to the camp.

The POWs were exhausted once they got back to the camp. Soon, well-equipped and well-armed German guards returned. Recall that when Lt. Col. Waters went out with Hauptmann (Capt.) Fuchs was carrying an American flag and a white flag, and it looked like the Germans were surrendering. They were not. About 30 minutes later, Waters was being carried in a blanket, having been shot by a German paratrooper. He was moved to a field hospital, survived, and made it home.

I want to underscore that all this action occurred in Bavaria, in southern Germany. Recall the fear that Hitler would retire with his forces to a Redoubt in Austria or the Bavarian Alps.

With this attempt to liberate Oflag XIII-B failing, the Germans told the POWs they were to catch a train at Hammelburg. They boarded box cars, 37 men and two German guards in each car, and traveled southeast, arriving at Stalag XIII-D, Nuremberg, on April 1.

Stalag XIII-D was a very large POW camp. One well-documented source said that at the end of 1944, the camp had 29,550 POWs. Some 14,000 of these were Soviets, 11,000 French, and the rest were Italians, Belgians, Serbs, Poles, and some few British and Americans. Of the total, about 8,680 officers were separated into Oflag 73 located at the same site.

The Nuremberg Stalag-Oflag became a destination for POWs from other camps. Many men from camps in western Germany were moved to Nuremberg. Because of this enormous influx, POWs had to be marched out, and most of the marching was into the heart of southern Bavaria and toward Austria, toward the area where the Allies worried about a German National Redoubt.

On April 4, Col. Goode and his crew from Oflag 64 began their second march (blue arrows on the map above) on a trip that would take them farther south, to Moosburg. By now, of course, they were marching with many other POWs from all over the European theater of war. They marched some 90 miles through several towns and villages and, after about two weeks, reached Moosburg, the location of Stalag VII-A, on April 20, about 20 miles northeast of Munich in Bavaria. Note how close Moosburg is to Austria (colored green) and the Stalag located there.

This was a long march. The men were very weak, and Allied bombing in this region was constant. The Allies were fighting their way to Nuremberg, capturing it on April 17-20, 1945.

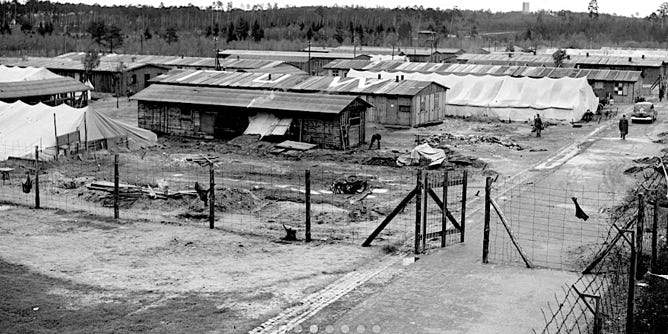

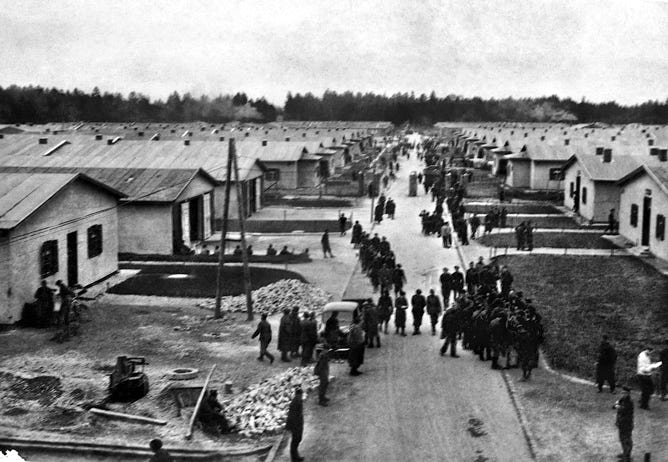

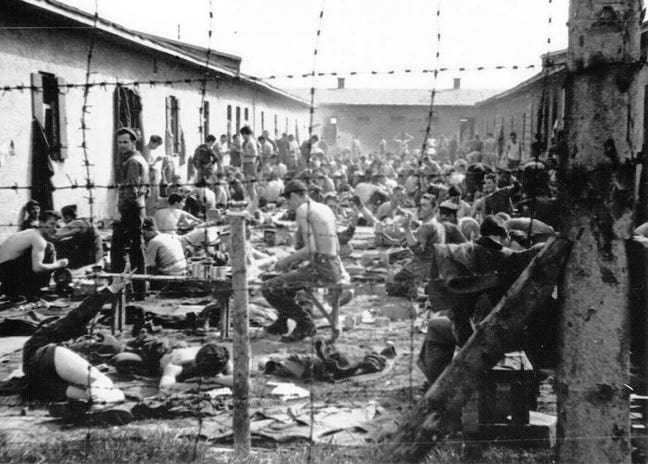

There was a great deal of chaos at Moosburg. There were POWs here from many nationalities. The estimate is that on January 1, 1945, there were about 76,000 POWs here, primarily French (38,000) and Soviet (14,000). I have seen estimates that the population rose to over 100,000 as POWs were moved from other camps to this one during the final days of the war.

Stalag VIIA at Moosburg was a big operation. It covered an area of 86 acres. However, it was not big enough to hold the approximately 110,000 POWs from an estimated 27 countries.

Eventually, tents had to be erected at the camp to house the tremendous influx of POWs. Estimates of the final population range from 110,000 to as high as 130,000.

By April 1945, General Patton's Third Army cut through Germany like a hot knife through butter. The American force had to fight its way through Moosburg and to the camp.

The German SS resisted about as well as it could, but the fight was short, and the SS surrendered.

Colonel Goode was the SRA-SAO for the entire camp. Some of the German administrative personnel remained at their posts in the camp, while the remainder, including the guards, were taken prisoner.

Even though liberated, most of the former prisoners did not immediately run out of the camp for good reason. They were unarmed, they had no idea what enemy forces were left, and they had no way of knowing how to get to safety on their own. Many did venture out to walk the Bavarian countryside, with some walking as far as Munich.

American artillery batteries set up shop in the fields near the camp. For their part, the troops who took the town uncovered weapons arsenals. Some prisoners walked the streets of Moosburg. Some broke into liquor stores and warehouses, food shops, and clothing stores; others took motorcycles and cars and rode them around. Most of the ex-prisoners threw themselves a party in the streets.

American support troops began arriving at Moosburg on April 30 with food rations. Capt. Frank D. Murphy, 418th Bomb Squadron, 100th Bomb Group, has written that General Patton arrived on May 1. He described Patton's visit this way:

"On May 1, 1945, a grim-faced Gen. George S. Patton, Jr., commander of the U.S. Third Army, paid us a visit at Stalag VIIA. He was dressed in a crisp, neat, fresh uniform and wearing his legendary wide black leather belt with a huge silver buckle to which was attached his famous paired set of ivory-handled six-guns. Maj. Gen. James A. Van Fleet, III Corps Commander, and Maj. Gen. Albert C. Smith, commander of the 14th Armored Infantry Division accompanied General Patton. As he walked briskly through the camp General Patton occasionally stopped and exchanged a few brief words with small groups of American prisoners. When he came upon my group the General paused, looked at us, shook his head in disgust at the sight of the thin, unkempt scarecrows standing before him, and said in a low voice, 'I’m going to kill these sons of bitches for this.'"

While the troops loved that kind of talk, a story by another prisoner reported that the arrival of two Red Cross women overshadowed General Patton's visit. GIs are GIs, thank God.

Capt. Murphy said they were deloused and allowed to bathe and shower, given new uniforms, and on May 9, they were trucked with other POWs to a former Luftwaffe base at Regensburg, placed aboard US C-47 transport aircraft, and airlifted to Liege, Belgium. Milton Long has recorded that over the ensuing days, the POWs were trucked to Landshute Airfield, and "hundreds of C-47s flew out the former POWs on their first leg of the trip back home."

That first leg was concluded at a place known as Camp Lucky Strike, about 40 miles outside LeHavre, France, which was used as a collection point and rehabilitation center for former American POWs. Lt. Kleber said being shifted to Camp Lucky Strike was “worse than the final days in prison camp because they were utterly unprepared for us. As a Scotsman once said, ‘The food is bad and in such small quantities … Lucky Strike was so bad, so poorly run. They had no plans for processing huge numbers of liberated prisoners. So they just told us to stay put, and they’d get us on a ship going home. If your name came up and you weren’t there, your name went to the bottom.”

Kleber commented that while aboard his ship heading for home, he was convinced “there was a U-boat lurking out there which had not gotten the word or whose captain wanted to sink one more ship for the Führer.” He made it home.

For his part, Murphy was X-rayed and found to have a touch of pneumonia and was down in weight by about 50 pounds. He was treated in hospital for two weeks with a new miracle drug, penicillin, released, and put on a commercial ship, re-fitted as a hospital ship, and sent home in a 30-ship convoy. The crossing took 12 days.

Lt. Sanford tallied the miles endured on the Oflag 64’s Long March: 439 miles and 82 days on the road.

Lt. Kanners came up with this prayer while he was on the march:

“We give thanks today for the greatest gift that man can know. To be an American, and live in America.”

__________

Go to Oflag 64, The “Lone Rangers”

Click to zoom graphic-photo

Table of Contents

Table of Contents

Table of Contents

- Overview

- Part 1: Sczubin to Ruhnow

- Part 2: Ruhnow to Luckenwalde

- Part 3: Sczubin to Moosburg

Table of Contents

- Overview

- Part 1: Sczubin to Ruhnow

- Part 2: Ruhnow to Luckenwalde

- Part 3: Sczubin to Moosburg