DUTY, HONOR, COURAGE, RESILIANCE

Talking Proud: Service & Sacrifice

Kriegies of Oflag 64, WWII

Introduction

My greatest fear while flying during the US-Indochina War was becoming a Prisoner of War (POW). The question that dogged me was whether I, an Air Force officer, would serve honorably as a POW.

“Experiences of captured Americans reveal that to survive captivity honorably would demand from you great courage, deep dedication, and high motivation … Keep faithful and loyal to your fellow prisoners …”

Jackson State University, MS

The National WWII Museum in New Orleans says there were about 94,000 Americans held as prisoners of war (POWs) in the European Theater of that war. The Museum notes,

“The experience of captivity was a ‘life within a life’ for many Americans.”

“Oflag 64 Remembered” is the online home of the former POWs of the prisoner of war camp designated Oflag (Offizierslager - Officers’ camp) 64. The Germans established it during World War II in Sczubin, Poland, to detain captured American Army officers. The first to arrive came from the battles of Tunisia.

Colonel Thomas Drake, the commander of the 168th Infantry Regiment, surrendered his forces in Tunisia on February 17, 1943. He was the first Senior Ranking Officer (SRO) at Oflag 64. He wrote this to his men,

“Let no man believe that there is a stigma attached to having been honorably taken captive in battle. Only the fighting man ever gets close enough to the enemy for that to happen. That he is not listed among the slain is due to the infinite care of Providence.”

I’ll borrow from a thought expressed by Major Robert Eckman, 168th Infantry, a POW at Oflag 64,

“For them, the war was over. But a new war was beginning, the personal war of prison camp life.”

Before WWII, the camp at Sczubin, Poland, was a boys' school. When war became apparent, the Poles closed the school, built some barracks, and used it as a billeting area for Polish cavalry. The Germans invaded Poland on September 1, 1939, found the Sczubin barracks, ringed it with barbed wire, added more barracks, and turned it into a POW camp.

Initially, Oflag 64 was home to captured French, British, and Soviet officers. In June 1943, it became exclusively a POW camp for American Army officers at the rank of full colonel or below. The first to arrive came from Tunisia. They numbered about 150. They were among the first Americans to fight in WWII Europe, having landed in North Africa as part of “Operation Torch.”

Later, Oflag 64 received officers captured throughout Europe, from Sicily, Italy, Normandy, the drive across France, and the Battle of the Bulge in late 1944. Its population would rise to over 1,400.

This report deals with when Soviet forces closed in on Germany from the East and Allied forces closed in from the West. Germany knew it was in trouble. In January 1945, the Soviets surged across Poland and then into Germany. The Soviets pressured Germany’s POW camps in Poland and eastern Germany. The red dot marks the location of Oflag 64. The Soviets had to pass through it to get to Berlin.

The Germans had to make a quick decision about their POWs as the Soviets approached,

• Leave men in the camps in relatively good condition for the Soviets, who were only hours away, and avoid later allegations of inhumane treatment.

• March the POWs out, understanding the inhumane conditions to which they would be exposed in January in Poland, and keep the POWs to use for future negotiations.

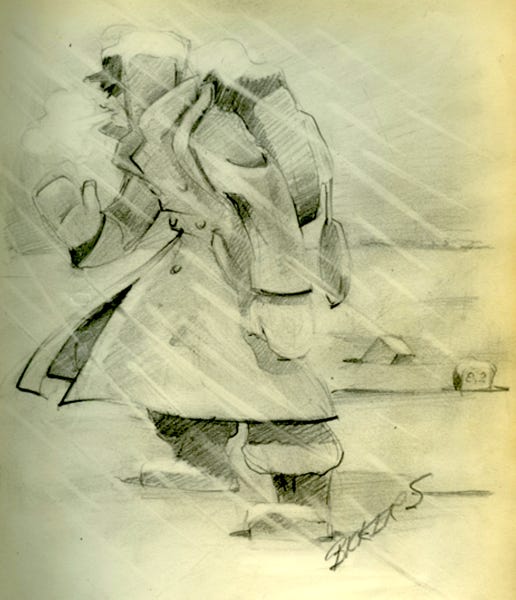

The Germans chose the latter option. The Germans moved thousands of POWs westward. Many died during the march or their escapes from the march. Many also made it to liberation. An untold number suffered for the rest of their lives. The drawing by Alan Moore shows Australian POWs marching through Germany during the winter of 1944.

The stories of Oflag 64 POWs revolve around their “Long march out” and the many personal wars that resulted.

While preparing this story, I have thought more than once about what goes through a military man’s mind the moment the enemy captures him.

Lt. James Godfrey, 109th Medical Detachment, was a medical doctor in the North Africa campaign. He wrote,

“On that Valentine’s Day, the German storm burst upon us like a tidal wave. The great Tiger tanks with their heavy cannons blasted our few tanks like ducks knocked down in a shooting gallery. The swift panzer units with their infantry rained rifle and machinegun fire on (us) mercilessly while the dive-bombing Stukas screamed down from the sky to wreak havoc and death with their bomb loads … Our men … were in shock, most were terrified, men were screaming, men were bleeding and dismembered and dying and dead, and that is war … So swift and devastating was the battle that the Germans occupied our location quickly and I had little time to even offer aid to our wounded before I was taken prisoner by an Afrika Corps officer. Those of us who lived were dazed and bewildered, incredulous that such a calamity could happen.”

Capt. James H. Watts commanded Company A, 81st Chemical Mortar Battalion. He and his men were captured near Distroff, France, east of the Moselle River. He has expressed what he felt like when captured,

“When you are first captured, and particularly when you are surprised to find yourself still alive, you are in a state of shock. We were marched out of the town across an open field. Our artillery was firing a steady barrage around the perimeter of the town to prevent, or slow down, German reinforcements. The seven of us were walked through that barrage. As the shells impacted anywhere near us the German guard would hit the ground. We remained standing and did little more than bow or droop our shoulders and would look down at the guard with a feeling approaching contempt. After all these years, it is hard to make the family realize that you just didn’t care what happened to you so soon after your capture. With the passage of time, you became normally interested in your safety.”

TSgt. Aben S. Caplan, 15th Infantry, captured on the German side of the Rhein River, wrote,

“The thought of becoming a prisoner of war had never crossed my mind. It’s impossible to adequately express how depressed I felt at that time and how concerned I was about the worries I would cause those dear to me. I was marched away with tears in my eyes at my helpless position.”

Lt. Brooks Kleber, 359th Infantry, interviewed by Alexander Cochran, Jr., said he was on a four-man nighttime reconnaissance behind enemy lines three weeks after the Normandy landings. They found a gap in enemy lines, came under fire, and tripped a flare. He said,

“Two of my men were hit, and my carbine was smashed by a German round. Up until that point, I was doing things automatically, just like training. I wasn’t thinking about being captured. There wasn’t any fear, just almost excitement. (After surrendering) I started to tremble, but then I became concerned that the Germans would think this was from cowardice. It was just a natural reaction I guess. We had to carry our two wounded, although both were dying … The Germans put us in a barn by ourselves. At that point, a tremendous sense of depression overwhelmed me … I shouldn’t be proud of it because it represented a breakdown on my part, a severe reaction.”

The Germans captured Lt. Joseph Zelazny, 1278th Combat Engineering, on December 21, 1944, in Martalegne, Belgium. He said they stripped him of everything of value, then lined him up along with Moore, his jeep driver, and Kimbuel, his guard. Once lined up,

“(They heard) the hammers come back on their pistols 25 ft. away … Moore was hit in the right side, Kimbuel in the small of the back (he died next morning in Germany), and myself was hit in the left shoulder … They shot everyone they caught and I counted seven of my men which got shot and I watched out the window and couldn’t help them. Sure a day I will never forget.”

This report addresses the “personal wars” of POWs at Oflag 64, for the most part expressed by them, during the period from January 1945 through liberation in May 1945.

Writing “Life in a Unique Nazi POW Camp,” Duane Schultz, a historian, paints a picture of Oflag 64 as “among the best of all German POW camps.” Perhaps so. The camp had a 3,000-book library; high school and college courses were taught; they had a baseball league, a newspaper, a jazz bank, and an orchestra, and the men performed plays and built sets for those plays. That’s all true. The POWs will tell you they made the best of their situation.

Capt. Thornton V. Sigler, 175th Infantry, wrote this in his journal,

“After reading (my) description of life as a POW in Oflag 64, you may get the impression that it was a vacation for us. Don’t believe it! … The guards stole our Red Cross parcels, we rarely had running water, fuel for the stoves was practically non-existent, we were infested with lice, the goons paid no attention to the Geneva Convention, we were constantly being searched and threatened with death, we got no mail, we were under constant surveillance by guards we called ‘weasels.’ I suppose the way we were treated was a form of brainwashing. Worst of all, though, was the lack of food. I entered captivity at 165 lbs. I came out at 127.

“Unless you’ve been in this situation, there is no way you can fully understand the boredom, frustration, and fear for your life that we lived with 24 hours a day. When you read, try to put what you read in perspective … Prisoners of war are desperate people and will seize upon any activity in order to keep their sanity.”

The POWs were known as “Kriegies.” Kriegies is short for the German word "Kriegesgefangenen," which means prisoner of war.

Toni Reavis's website, “Wandering in a Running World,” said,

“In that bitter winter of 1945, approximately 53 percent of all American POWs in German camps were moved westward …”

The Germans at Oflag 64 marched out about 1,200 POWs and left some 200 sick and wounded behind.

This report is in sections:

Long march out

Last but not least, The “Lone Rangers”

One final note: I frequently quote POWs and those writing on their behalf. I take their quotes as presented, disregarding grammar and spelling. I accept the credibility of their remarks, though some details may conflict with those offered by others. I am conscious of “the fog of war.”

__________

Click to zoom graphic-photo