DUTY, HONOR, COURAGE, RESILIANCE

Talking Proud: Service & Sacrifice

The Lone Rangers

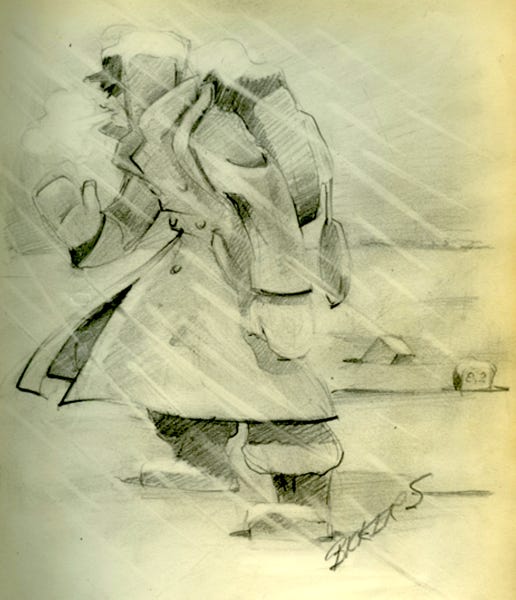

Graphic by Lt. James F. Bickers, USA, POW Oflag 64

Last but not least, the men I call “The Lone Rangers.”

It is hard to determine how many men from Oflag 64 survived the war and made it home.

I want to draw attention to three groups of men from Oflag 64 who were not in the group that marched from Poland to Luckenwald or Moosburg in Germany. For lack of a better title, I call them the “Lone Rangers:”

• Those who were left behind starting on January 21, 1945

• Those who left the long march column and returned to Oflag 64

• Those who left the column and escaped

The stories of these men are striking. They often were on their own or in very small groups. They made their way by whatever means through unfamiliar countries. Most could not speak foreign languages, and they were often without maps. They walked and rode away from the Germans and toward the Soviets, following the sun, not knowing what was ahead.

I convey their stories one by one.

Corporal Thomas Lawson, 30th Infantry, attended an Oflag 64 reunion in 1987. He explained,

“Even though our adventures were similar, each and every man lived it in his own unique way.”

You will see how true that is as you go through the bold adventures of the “Lone Rangers” of Oflag 64.

__________

Dr. Peter Graffagnino said when the main body of prisoners was marched out, they left “about a hundred or so prisoners in the camp, the infirmary patients, some doctors, men who couldn’t walk or feigned illness, and a group of others who hid out.” Lt. Victor Kanners remarked, “men were being left behind in the hospital with one German soldier.”

Col. Paul Goode reported to the War Department that about 71 men were left behind. He said further that 241 men successfully escaped.

Col. Frederick Drury was the SRO for those left behind.

Estimates were that the Russians were only 23 miles away when the Kriegies were marched out on January 21, 1945. The Soviets were so close that Lt. Kanners expressed concern that they might blow up the camp buildings.

__________

On January 19, 1945, while at Oflag 64, Lt Robert L. Cheatham, Jr., 26th Infantry, wrote he “became violently ill. Threw up. Fainted. Prison hospital. High fever. During night hallucinations. Girl bathed my brow. Fever broke. Exhausted. Weak.”

On January 21, Cheatham said a German and American doctor stood at his bed. The American doctor feared he had appendicitis, so he stayed behind.

Cheatham said on January 23,

“Soviet Army arrived. Tartar Infantry-Katusha rocket trucks. Jeeps with Jerry cans for gasoline, some filled with Vodka—Studebaker trucks by the thousands. Russians liked ‘Studebaker,’ which was a code word used to identify us Americans. The next day, a huge bear of a Combat Engineer Captain walked in and said in broken English, ‘Anybody here from Minnesota?’ We talked for hours. Captain Kakkonen’s family had gone from Minnesota to the Soviet Union in the early 30s, responding to Soviet appeals to ethnic Russians overseas.”

On January 28, the Soviets transported Col. Drury’s group, the sick Americans left at Oflag 64 and those who had escaped or left the march and returned to Oflag 64, to Rembertow, Poland, by truck. They arrived there on January 31.

Cheatham said the Russians moved him and others on the Studebaker trucks to a suburb of Warsaw, probably Rembertow, a trip that took several days.

Rembertow is a district on the far northeast side of Warsaw, on the east side of the Vistula River.

Rembertow has a sordid history, the site of a very harsh POW camp in WWI. It was also designated as one of 14 Jewish residential districts under German occupation. The Germans drove out 1,800 Jews from Rembertow, ultimately to death camps. The Germans brought more than 1,000 Jews from the surrounding area to labor camps in Rembertow and killed all of them before the war’s end.

As far as I can tell, the Soviets used Rembertow as a gathering place for Western POWs, a place where they could account for them and ship them off. Some POWs took that route, while some escaped from there and went elsewhere.

K. Karlsbad, a Polish underground warrior, in Pages Torn from my Youth, described Rembertow as,

“A temporary Russian concentration camp (near 'liberated' Warsaw) where thousands of political prisoners were waiting for transport to Siberia."

The Soviets moved Drury's group, which numbered in the hundreds by the time they were moved, to Odesa by train on February 22. They reached the Odesa port on March 1 and were taken home by ship or plane. Some of the sick boarded a British ship to Cairo and on to a US hospital. Others have said they went by ship first to Istanbul, then to Cairo, and then to Naples.

Cheatham made it home in April.

Odesa was in Soviet-occupied Ukraine, on the Black Sea, and was a point of embarkation for many POWs back to the US.

The first Soviets arrived at Oflag 64 on January 23, 1945, just two days after the bulk of Oflag 64 POWs marched out, about 1,200 strong. Keep in mind that the Soviets had Berlin as their target. They were passing through, yet at a top level, they knew the value of the Americans they were about to liberate.

__________

When the Oflag long column started to march out of the camp on January 21, Capt. Frank N. Aten, 701st Tank Destroyer, who had unsuccessfully attempted escape four times, snuck away into the hospital and hid in a stairwell. After he was convinced the Kriegies had marched out, he emerged, cut through the fence, saw the guard towers were not occupied, and “headed towards the East.” He had told his platoon sergeant to take the lead if he did not return. This marked his fifth escape attempt since being captured. Lt. Otis “Brad” Bradford called Aten “our escape artist.”

During his first day, Aten found a barn and hid in it. He commented, “Freedom ‘felt’ good, but my first night as a free man was very cold and restless.”

Capt. Aten decided it would be best for him to return to Oflag 64, which he did, sliding through his hole in the fence and back into the hospital, where he bumped into five other POWs. On January 23, the Russians arrived. He said,

“Kriegies began returning to the Oflag. It became a rallying point because this was the only place where they knew how to get to. Our group included twenty who had been left in the hospital and three who emerged from the tunnel.”

Aten continued,

“Colonel Millett, the Executive Officer, and Jake Winton from New Jersey were among the returnees. They teamed up with Bill Fabian and me to make our travels back to the USA. Bill and I found out that there were many sick and wounded in the local Schubin hospital, in addition to all of the Americans in the Oflag hospital, and they all had one thing in common--supplies and food were in short supply, everywhere, and they all needed help. The answer seemed to be 15 to 20 miles away in a large church. It had been taken over by the Germans and was used as a warehouse. If only we could get the supplies! Bill and I scoured the town for some kind of transport.”

He convinced a farmer to loan them his tractor and trailer. They found a Catholic church and “an enormous inventory of food, clothing, ammunition, and other things. In one corner of the sanctuary, thousands of Red Cross parcels were stacked, almost to the ceiling.”

This discovery angered Aten’s partner, Lt. Bill Fabian, 82nd Airborne, who was angry at the Nazis for depriving them for so long. They convinced the locals that the people in the hospital needed all this stuff, so they agreed to let them take all the parcels their tractor-trailer could carry. After they delivered the parcels, a lot of partying involved the Russians and Poles. A drunken Russian pulled a gun on Lt. Bill Murphy and began kissing him. Murphy was captured in Cape, Italy. Aten grabbed a portable heater and hit the soldier in the head, killing him. They buried him. The next day, they hopped on a ride on a Russian truck bound for Warsaw.

Eventually, Aten made it to Odesa and boarded a British ship to Port Said, Egypt. He met up with some British soldiers who challenged the Americans to a fight. Once the fight began, other British and American soldiers joined in. The Shore Patrol and Military Police (MP) arrived and settled things down. Aten and Lt. Jake Winton boarded a Liberty ship to Naples, and they got on an American ship bound for home. Liberty ships were a class of cargo ships built in the US during WWII under the Emergency Shipbuilding Program. The design was adopted for simple, low-cost construction. They were mass-produced.

Aten said while on the Liberty ship, he observed some Frenchmen throwing a man overboard, asserting he was a German sympathizer. And then, in Naples, he was asked to witness the hanging of three American soldiers found guilty of murder and rape, all Black. Aten commented,

“I had been a soldier for much of my lifetime, and as such, had witnessed many horrible and disturbing things, but none affected me as deeply as these hangings. Death is so final--whatever the reason.”

I want to insert a note about Aten’s earlier escape attempts, as conveyed by his family. Lt. Aten was captured in Tunisia. A German train was moving him from Capua, Italy, to the Brenner Pass between Italy and Austria. After a short stop, he “balanced himself on the open window, set his feet in motion to match increasing speed of the train, and managed to jump without injury.” He planned to get to Switzerland. Locals recognized him as a potentially dangerous foreigner and reported him to the Carabinieri police.” He was put on another train.

The family noted, “Eventually after multiple escapes, the German hierarchy became aware of his Houdini abilities and tagged him as an ‘escape artist’—not as a compliment but as a reminder that his antics would jeopardize his chances of survival. ‘Stay in the camp. The war will soon be over and you can go home’ they cautioned him. These not-so-disguised threats only encouraged Frank to envision the next escape plan.”

__________

Corporal Thomas E. Lawson, 30th Infantry, started on the long march. His buddy was Eddie Weirzgacz, who was from Chicago and spoke Polish. They decided to hide in the farmhouse complex, feeling they could achieve a better outcome if they went out on their own. They found a section where a concrete box had been constructed inside the barn, about a foot between the concrete wall and its wooden outer wall. They were malnourished and skinny, so they crawled between the concrete and barn wall. The German guards with dogs searched for them, but it was so cold, and the Russians were nearby, so they gave up.

Lawson and Eddie finally emerged and found a fellow POW left behind suffering from frostbite. They wrapped up his feet and started a fire to warm him. They remained in a farmhouse until they spotted a Russian captain on patrol. The captain suggested they head toward the Russian lines, which were not far away.

The next day, they set out to the Russian lines. As they got close, the Russians saw them and opened up with “everything they had.” They scrambled away and went back to the farmhouse. They waited a few more days, came upon another Russian patrol, and again tried to get to the Russian lines. This time, they made it and remained with the Russians for a few days.

Lawson said everyone was getting drunk on vodka, including a Russian captain. The captain took them outside, commandeered a tank, and they headed out. Lawson said the driver was as drunk as the captain. He ran off the road into a snowbank. Lawson and Eddie decided to go back to Oflag 64.

By this time the Russians controlled Oflag 64. Once again, the Russians drank themselves into a tizzy, so Lawson and Eddie decided to leave. They hiked and hitched their way to Warsaw. They got a ride from a Russian soldier. The Russian was about to drive the truck into an icy river. Eddie and Lawson jumped off before the driver and vehicle hit the water.

The two made their way to Minsk, now the capital of Belarus. They met up with other POWs, one of whom reached the US embassy in Moscow. The embassy arranged to get the men in Minsk to Odesa by rail, after which they caught a British ship to Port Said, Egypt, under American control. Lawson said he spent 535 days from the date of capture to American control.

__________

Wright Bryan, an associate editor for the Atlanta Journal, was captured by the Germans and wounded in the leg. He was taken to the Ofag 64 camp. He wrote,

“As (the others marched out), the German officers handed the keys of the camp to Chaplain Stanley Brach … and we were once more under full command of American officers.

“Quickly we painted large Red Cross flags to hang on all sides and the roof of the hospital … The senior American officer remaining in camp assured us we had adequate food and fuel supplies for several weeks and, ‘The Russians will be here either tomorrow or the next day or next week, or next month, we don’t know when, but they will be here.’”

Two days later, “A vehicle stopped between two principal German barracks across the street from the hospital and heavily armed men scattered to search the premises… When officers came to our gate, we saw they were Russians.”

Bryan said Russian troops came to the camp “in large numbers, riding tanks, trucks, jeeps and motorcycles, and in the afternoon the infantrymen came.” He wrote that Polish people from Sczubin town brought fresh bread and helped repair broken facilities at the camp. The men hoisted an American flag, which flew next to those of Russia and Britain. They were free to walk about. He concluded, “We are confident this area is firmly in Russian hands and we know we will be evacuated soon.”

__________

On the day they were to march out, Lt. Col. Tom Riggs hid behind a walk-in ice chest in the mess hall. He then walked to the outskirts of Poznan, about 55 miles southeast of Sczubin, where he met up with the Polish underground. He then joined up with a Russian unit that arrived in the city. The Russian colonel said Riggs could come with them to Berlin, so Riggs fought with them for 10 days and was put on a train in Warsaw that took him to Odesa.

John Hanlon, writing “Lt. Col. Tom Riggs’ Remarkable WWII Odyssey” for the Providence Journal, said,

“There (Odesa) (Lt. Col. Riggs) talked his way onto a British tanker for the 500-mile lift to Istanbul, Turkey. The tanker captain passed him onto a British freighter bound for Port Said in Egypt, some 1,000 miles away and considerably off Rigg’s course. It turned out well enough, though, because at Port Said, with the help of the Red Cross, he caught a ride on the troopship Mauritania, heading some 1,800 miles to Naples, Italy. There, for the first time in nearly three months, Riggs checked in with the American military.”

Incredibly, Riggs wanted to get back to his outfit, the 81st Engineers, and by hook and crook, he made it. He said when he “walked into the 81st Headquarters … everyone was astonished to see me.”

__________

Lt. William Cory, 805th Tank Destroyer, was one of those who hid in the tunnel until Col. Drury said they could safely come out. He stayed in the tunnel for about a day after the men marched out and then remained in the camp for about five days.

Cory debriefed that there were about 140 Americans at Oflag 64 at the time, including those who marched out and returned. He noted that many French refugees and escaped British POWs had made their way to Oflag 64, and the Russians evacuated them as well.

Cory said a Russian officer who could speak English arrived and arranged for the evacuation of all the Americans to Rembertow.

Lt. Cory and a few others left Rembertow looking for an airfield and aircraft that would take them to Moscow. They ended up in Lviv, then in Poland. The Russians jailed them as possible German spies. They worked their way out of that jam and made it to Miami in February 1945 via Teheran, Cairo, Casablanca, the Azores, and Bermuda.

__________

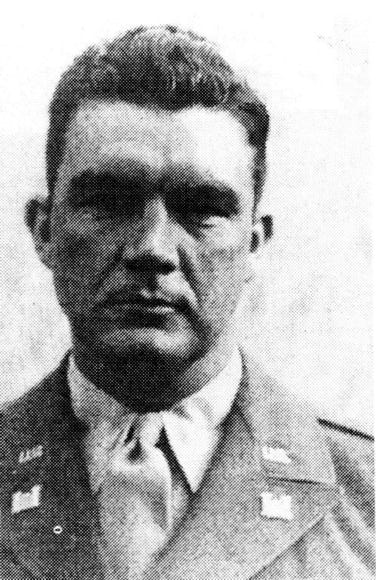

On the second day of the march, January 22, 1945, Lt. Herbert L. Garris, 377th Parachute Field Artillery, shown here, Lt. Carl G. Bedient, 506th Parachute Infantry, and Lt. Clarence Brown, captured in France, hid in a hay storage area. He said all the guards except for three left the camp with the column. As a result, the three stayed under the hay for another day. Garris remarked, “January in Poland is cold at best, but in a hay loft, it is hell!”

Garris and the others emerged from hiding in the hay loft at the dairy farm on January 23 and spotted other American officers in the farm’s courtyard. They then moved to the house to get warm and eat whatever they had or could find. He said there were “85 officers who had been left sick or had escaped along the road. Colonel Edgar A. Gans,” 3rd Armor, assumed command.

Russian elements arrived. A Russian tank lieutenant spoke to Col. Gans and assigned a Russian lieutenant and four soldiers to escort the group. Garris and the others became restless and decided to leave for Moscow. In a group of 29, they made their way by train and truck to Rembertow. They then grabbed a freight train to Brest on the Russian (now Belarus)-Polish border.

Garris said, “We reached Brest and became an integral part of one of the largest crowds I was ever a part of. There were thousands of refugees from Germany and wounded soldiers of every conceivable nationality heading for Lublin, Minsk, Smolensk, Moscow, and Leningrad.” Again, they made it to Odesa on the Black Sea by train. They worked their way onto a Liberty ship. They sailed to Istanbul.

From Istanbul, Garris traveled to Naples, where they were to embark on a ship to the US. However, he and a small group were granted permission to return to their respective units in Dusseldorf, Germany. He took a C-47 transport aircraft to Marseille and joined the 101st Airborne Division, which was on Rest and Recuperation (R&R). He was able to return to North Carolina with the 82nd Airborne Division.

__________

Lt. Richard B. Parker, 422nd Infantry, shown here, marched out, but on the morning of January 22, he said, “We were quite startled to learn that all of us too sick to march would be left behind. (Lt. James) Hesse (423rd Infantry) and I were both in misery as a result of our bowels and feet; we didn’t march. There were about 200 of us who didn’t.”

Parker said a Russian driver came down the road in a Sherman tank. The Russian promised to send trucks to take them to Moscow. After three weeks of waiting and no Russians, Hesse, Parker, and a Polish-speaking boy from Detroit set off for Warsaw. They then went to Rembertow and caught a train that got them to Odesa in early March. They waited a week and boarded a ship, and out they went.

__________

Lt. Thomas M. Holt, captured in Tunisia, said, “Approximately 75 to 100 POWs … decided that this march back into Germany was not for us, so the 75 POWs hid out in every conceivable place in camp. The German guards blew their whistles and lined up approximately 1500 to 2000 POWs who were left; out the main gate, they walked in a blinding snowstorm. The German guards had made no attempt at calling rolls.”

He said that after about 24 hours, the Russians rolled in. Those in the camp “broke up into smaller groups of twos, threes, even sixes, and out the gate we went, never stopping to look back.” Lt. Holt’s group consisted of five POWs, including Lt. Victor Danylik, who was captured in Italy. Danylik spoke Polish and Russian.

Lt. Holt said they walked to the northeast. In the span of about two months, to the end of March 1945, they walked to Odesa. They occasionally took the train or rode on a truck, but most of the journey was walking.

__________

Lt. Charles G. Eberle, 34th Infantry, escaped the first night of the long march at a large farm. He said he was going out to get some milk and was told to “Halt.” He initially thought that the guards were German, but they were not. They were Russians, “big tall guys.” A Russian major gave him a ride in his jeep and dropped them off in Warsaw. Eberle had an American flag. He said the Poles were welcoming, fed them, and enabled them to stay for a few days. He got on a train and spent seven to nine days in a boxcar to Odesa for the trip to Port Said.

Eberle said his ship out of Odesa was the last one the Russians would permit. He said, “No other ship was allowed by the Russkies to pick up POWs. The Russians took others and off to the cold country with them.” He believes the Russians kept them. He would later say, “We all said we’re going to be fighting these sonofabitches next, the Russians, because they had no regard for you at all.”

__________

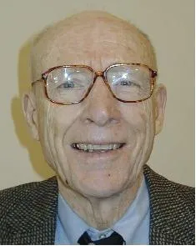

Like others, Lt. Mays W. Anderson, 750th Tank Battalion, marched out the first day. He said they arrived at their first destination in a “very weakened condition.” He said the weather was “as low as -50 degrees.” He slept between two cows to stay warm. When he awoke, he said Capt. Dr. Vincent Di Francesco, shown here, “approached me and said, ‘Do you want to go on like this or shall we try to escape.’ I answered that ‘we might as well be dead as go on like we were.’”

Writing a story about Anderson, Norley Hall said they hid in a haystack. The Germans were in a hurry and did not do a good check on the POWs. Once they felt they were in the clear, they emerged to find they were among 25 other POWs.

Hall remarked that the German guards had given the sick a certificate vouching for their status. As a result, Lt. Col. Gaines J. Barron, 142nd Regimental Combat Team, told Anderson and the others they had to leave by daylight so they would not endanger those left behind because they were sick. Most of the 25 POWs left, but Anderson and Di Francisco stayed another night. The next day, they went into town and found a Polish family willing to take them in. Anderson said, “We were happy, for now no one was guarding us. No damned German to shout and scream at us and probe us with guns.”

The Soviets approached the town the next day, and they hopped onto a Russian tank. As the tank drove down the road, the two POWs saw enormous death and destruction, much of it caused by the Russians. The tank commander offered to take them to Berlin, but they declined. They were interrogated and beaten as the Russians thought they were Germans. They finally convinced them they were Americans, and the Russians turned them out. They walked and made their way to Rembertow. At Rembertow, they slept with the refugees.

Dr. Di Francesco determined that Anderson had a clot on the brain and made him lie still on his back for 10 days. The clot dissolved. Anderson said on Saturdays, the Russians “staged hangings of collaborators.” He went to one hanging ceremony and was invited to “participate in a gang rape of a Polish girl.” He declined.

In March, Anderson and the doc traveled by truck with about 350 American officers and 800 enlisted men to Odesa. The British there traded them for a group of Russians forced to fight for the Germans.

__________

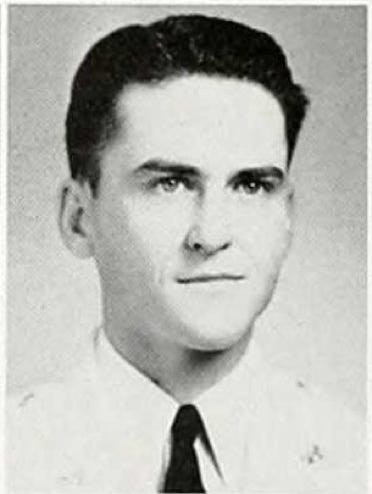

Lt. Richard Kellehan, 335th Infantry, shown here, was on the long march. But he said, “After walking 175 kilometers (108 miles), my CO (commanding officer) and I pretended to be sick and joined 40 other POWs in a boxcar. We traveled in this closed boxcar for a week without food or water in terribly unsanitary conditions.” They stopped at the Luckenwalde POW camp outside Potsdam. He added, “The Russians came up from Dresden on April 21, 1945.”

Kellehan and about 25 others were able to get on a truck, which took them to an airbase near Wittenberg. They got on a plane to the coast of France, “where people were cheering in the streets on May 7, 1945, because the war ended.”

Lt. Kellehan noted, “While we waited to be shipped back home, trucks with pitifully emaciated enlisted men came to the camp. We realize their experiences in the POW work camps must have been much more terrible than ours had been. And, of course, since our return to the States, we have learned how much longer and more severely others had suffered for our country.”

__________

In writing about Lt. William “Bill” Korber’s diary, Jerry Miller reflected a similar thought. Miller said, “There was actually some guilt for being captives, and the priest once said of those still in the fight, ‘They are really fighting our battle for us.’” On some level, the POWs must have known that the men on the battlefield were having it worse.

__________

In March 1945, when those who were on the long march arrived at Hammelburg, Stalag XIII-B, Lt. James Cockrell, shown here, and a fellow lieutenant nicknamed “Lummy,” were “separated from the main group in the confusion somewhere near Hammelburg … Lummy and I and about a dozen prisoners under about the same number of German guards continued our march. The morning of March 15, I was not able to stand. My feet were cut by the ice and swollen by the cold and I could not stand … I recovered in a few days and could walk slowly. The situation was chaotic.”

Cockrell, captured in North Africa, continued to say he and Lummy went out to look for food and “came upon a German Volkswagen by the side of the road. Lummy was somewhat of a mechanic and wired around the ignition lock. He found that a 20-millimeter shell was lodged in the transmission. We got a couple of German boys to push us, and the darned thing started.”

Cockrell said they could only go 20 mph because the transmission was locked in second gear. They came upon a river and saw that it had risen enough to cover the end of the pontoon bridge. They didn’t know what to do. An American tank arrived, and after some quibbling where Cockrell had to pull rank, the tank took Cockrell and Lummy back to the American camp, and they were home free.

__________

Click to zoom graphic-photo

Table of Contents

Table of Contents

Table of Contents

- Overview

- Part 1: Sczubin to Ruhnow

- Part 2: Ruhnow to Luckenwalde

- Part 3: Sczubin to Moosburg

Table of Contents

- Overview

- Part 1: Sczubin to Ruhnow

- Part 2: Ruhnow to Luckenwalde

- Part 3: Sczubin to Moosburg