DUTY, HONOR, COURAGE, RESILIANCE

Talking Proud: Service & Sacrifice

Part 2: Ruhnow to Luckenwalde

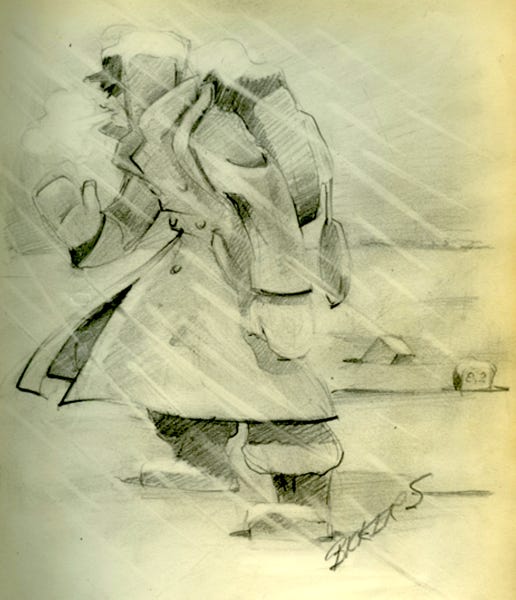

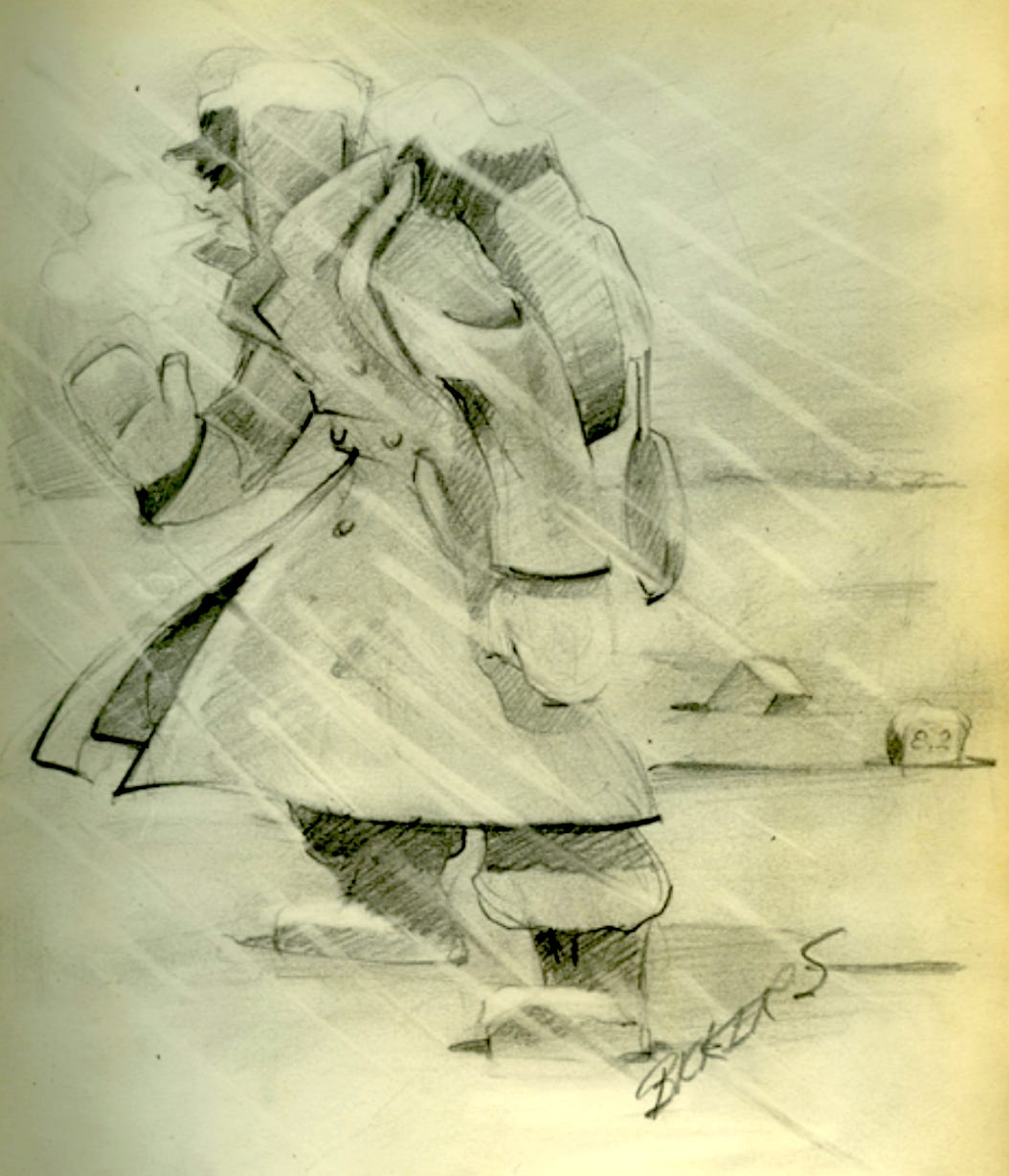

Graphic by Lt. James F. Bickers, USA, POW Oflag 64

It’s now February 5, 1945, and the Oflag 64 column has broken up into at least two sections. One group went to Luckenwalde, south-southwest of Berlin, and the other went to Moosburg in southern Bavaria, close to the border with Austria.

Let’s start with the crew that went to Luckenwalde, Stalag III-A. Oflag 64 men who had marched from Sczubin to Ruhnow and were not marched out from Ruhnow were boarded in railway boxcars at Ruhnow station. Many had pneumonia, infections, and “frozen feet.”

Watts commented on February 5 that “180 men were to leave by train. All bad feet have to leave … About midnight we are loaded into trucks and taken to the Ruhnow station (northwest Poland) and loaded into boxcars. We are 48 and 3 guards in our car and there are four cars. We sit in the yards all night.”

The train finally got going on February 7. Watts said one boxcar had a maintenance problem, so his car had to take on 20 more POWs, ramping up the total in his car to 71. He said, “Everyone must stand … Everyone cannot sit down so we must take turns.”

Lt. Otis “Brad” Bradford, 17th Field Artillery, stayed with the group that marched out, but only for about 10 days. On February 13 he suffered from the “trots … Was able to keep up (with the column) but barely.” By February 14 he was feeling weak, so weak that two comrades had to carry his blanket roll along with their loads.

On February 15, Bradford felt too weak to continue the march. The column left on February 16, and he stayed behind, saying, “Just couldn’t cut it. The boys left in the morning, leaving me under my hayrake. Just couldn’t cut it. The boys left a few supplies. Hated to see them go.”

Somehow, Lt. Bradford made it to Usedom after “a mercifully short hike.” He met up with nine others he knew. Bradford said about 100 POWs boarded the train at Usedom, just west of Swinemunde and very close to the Baltic Sea.

Lt. Jack Rathbone, who had been captured in North Africa early on, wrote to a fellow POW that he was “the third group to leave the march from Sczubin and be squeezed into a box car.” He ended up in Stalag III-A. I think he was on the same train as Bradford.

Doc Graffagnino has thrown me for a bit of a loop. He wrote that the marching group reached Stettin with some aid from a shuttling truck.” I think he is referring to the Szczecin Lagoon, which is close to Usedom. He wrote,

“We were taken by truck to the rail yards and loaded into two cars, a slatted boxcar for cattle, and an open coal car for which a tarpaulin covering had been provided. The accommodations were crowded and not very luxurious, but it was better than walking. We were headed for Berlin, and although Stettin is less than one hundred miles north of the capital, we were four days reaching the rail yards there—the German rail system was having its problems at that time.”

Graffagnino continued,

“In the Berlin rail yards, our two rail cars sat out three days and nights, back in the almost forgotten sounds of war. There were day bombings and night bombings, and some of the nighttime fireworks were spectacular displays. Miraculously there were no hits or near-misses in the vicinity of our sidetrack. And then one day we were moving again.”

He and his fellow POWs were on the same train as Lt. Bradford.

The net result is that at least two trains are carrying Oflag 64 POWs, one from Ruhnow and the other from Usedom. Both trains went to Stalag III-A at Luckenwalde, south of Berlin.

Capt. Watts said they traveled through Berlin and made it to Luckenwalde on February 10.

Lt. Bradford said his train ride was “long, uncomfortable, cold. But at least I was over my trots, which was a mercy.” He estimated they had walked 228 miles before getting on the train.

Bradford’s train arrived at Luckenwalde on February 20. Watts noted that about 100 officers arrived that day from the group that made the long march from Sczubin. I assume this to have been the train carrying Bradford.

Watts added that the word was there were about 450 left in the Sczubin column.

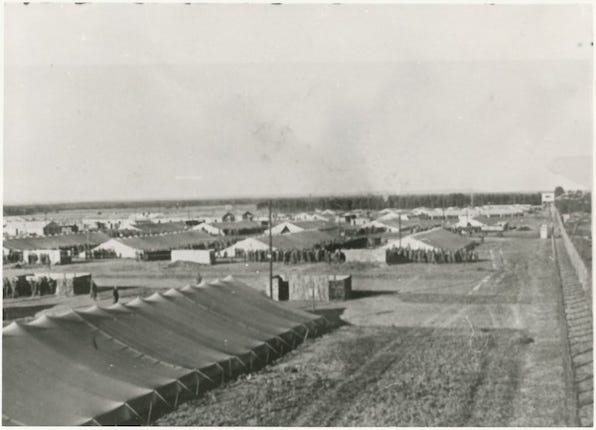

POWs from all over Europe were brought to Stalag III-A at Luckenwalde. POWs from France, the USSR, Serbia, the US, Britain, Italy, Poland, and Romania were there. Watts called it the “League of Nations” camp, meaning POWs from everywhere were there, about 15,000. He commented, “Looks like I did the right thing by sticking it out on the march.”

Lt. Bradford did not have much good to say about Luckenwalde. He called it “the worst permanent camp we’d been in - no Red Cross parcels available, few supplies or even bedding for some of the officers at first.”

He added,

“I remembered most vividly our introduction to IIIA. Our little group was marched up to a low building with overhanging roof, told to strip and pile our belongings in piles on benches outside the ‘shower room.’ After being closed in, we looked at each other, naked as jaybirds, skinny as scarecrows, every bone showing, wondering if this was IT. We’d all heard rumors of the German concentration camps, so we were busily examining the shower heads and drains, which to tell the truth didn’t look too authentic. But after a minute, I suppose, the water did come trickling in and we happily applied the delousing compound and rinsed ourselves. With great relief.”

Graffagnino estimated there were over 17,000 men of all nations at Stalag III-A, with more arriving daily. He said,

“The already overtaxed camp organization was completely overwhelmed. More than 4,000 newly arrived American enlisted men were living on bare ground covered only by soggy straw under six circus-type tents on a mud-and-snow-swept clearing. One large open-pit latrine and one water point served them all. By contrast, as officers, we lived in luxury, sleeping on bunks in barracks and with two aborts (latrine buildings) for our convenience.”

He continued,

“Under such conditions, there was not much we could do but exist. We accumulated sack time, we talked and swapped stories, argued and griped, played cribbage and cards, worked at tinsmithing. When the weather permitted, we walked outside within the limited confines of our barbed wire enclosure; sometimes we just stood on the rise next to one of the latrine buildings and watched in fascination the new, German jet fighters, which occasionally whooshed by overhead. But mostly we planned menus; long, detailed 12-course meals that someday we hoped to eat again.

“Sex was never a topic of conversation. We had discovered long before that it ranked far down the list of man's basic drives; we concluded that Freud had never been cold or really hungry. It was a depressing, monotonous, gray existence.”

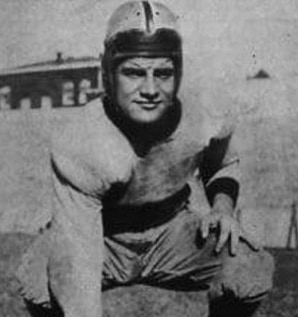

On a lighter note, Lt. Bradford told a story about Lt. Edward “Eddie” Berlinski, captured in North Africa, and Lt. Lynn M. Hunsaker, Light Rangers, captured in Italy. Bradford said Eddie Berlinski was a football player from Rutgers, even after being a POW, still 200-225 pounds. Hunsaker was the smallest guy he could find. Berlinski got hold of a three-foot piece of 2x4 wood. Eddie and Hunsaker screamed and shouted, and Eddie chased Hunsaker around the barracks, with Hunsaker staying a few paces ahead of Eddie. They ran around, upset some tables, jumped into bunks, and out the windows. “The two of them disappeared into the washroom at the far end, kept up shouting and banging for 10 seconds probably, following which they emerged with arms around each other like the good buddies they were … The whole deal was so bizarre and outrageous in its conception and performance that I (Bradford) still get a charge out of retelling it.”

Eddie Berlinski was a North Carolina State University Wolfpack football player, “the best halfback of his era … also a flashy guard for … the basketball squad and a speedy center fielder for … the baseball team.” I’ll get more into Eddie’s escapades with Lt. Herbert L. Garris in the Lone Ranger section, but Berlinski and Garris escaped from Oflag 64.

Lt. Bradford talked about the bombing in Berlin,

“I remember the loose wooden doors of the (Luckenwalde) barracks right by our cubicle. The almost nightly bombing of Berlin would make them rattle as if someone were standing outside them and beating on them with fists.”

Capt. Watts reported,

“This constant hunger is hard on the nerves as well as the constitution. Hunger seems to be like a progressive disease. I hurt more each day … By this time we are suffering from hunger and have experienced significant weight loss. When this happens everyone is focused on food to the exclusion of almost anything else.”

Watts later noted that the “Place is alive with rumors and 90% revolve around food.” Throughout this period, the men scrounged for food and made all manner of trades to get what they wanted and give what the others wanted. On March 16, he said he got food, the first he had to chew.

On March 17, Watts noted that “the rest of the column is at Hammelburg,” about 120 miles southwest of Luckenwalde. All the POWs could do was scrounge for food, trade whatever they had to trade, and stay posted on the Allied advances.

Watts said on April 11, 1945,

“The camp is rife with rumors. Your spirits were to the sky one moment at some supposed war breakthrough and dashed to the depths within a short time when the rumor was found to be false … My solution was to form a rumor service with a Lt. Ellis from the 82nd Airborne. People would bring us a rumor, and we would run it down. Usually, we find that wishful thinking had created the rumor.”

The Germans reported President Franklin D. Roosevelt dead on April 13. The first Soviet units entered Berlin on April 21.

On April 21, 1945, the POWs took control of Stalag III-A at Luckenwalde. The German guard company left. Watts said, “The place is a madhouse right now.” Norwegian General Otto Ruga (Ruge) took command of the POWs as the SRO.

General Ruge took command of Norwegian military forces on April 10, 1940, one day after the Germans invaded Norway. His predecessor, General Kristian Laake, resigned after urging the government to negotiate. General Ruge urged the government to resist, and he led the resistance. The Norwegian government capitulated on June 10, 1940, and Ruge became a POW. Hitler insisted he be transferred to Germany. He was transferred to a German POW camp in Poland in late 1943. The Germans evacuated him to Luckenwalde as the Soviet forces advanced in the winter of 1944-1945. He remained as a POW for the duration of the war.

Lt. Bradford commented,

“German garrison drifted away today quietly. We took control of the camp before they were hardly away. Russian POWs going wild - poor devils - they’re surely entitled to it. German units remain in vicinity of lager (camp). Increased artillery fire on all sides. Raining.”

Capt. Watts boasted, “We now have several German prisoners in the guardhouse, men who stayed behind for that purpose and ones who gave in to our patrols.”

Lt. Rathbone gloated a bit himself,

“When the Germans pulled out of the camp on April 21st they were astonished and upset to see an allied guard detail, complete with armbands, moving out to set up guard posts around the camp. Such was the internal organization that had been developed under their noses. The Russians blew in the next day.”

Watts observed that Russian armored cars entered the camp on April 22, and Russian aircraft were overflying the camp. The Russians took over the camp and flew General Ruge to Moscow.

As a historical point, General Ruge reportedly negotiated an agreement with the Soviets wherein Norwegian POWs could be liberated to Norway through Denmark rather than through Murmansk, USSR.

Lt. C.A. Williamson, 143rd Infantry, was a bit annoyed,

“I was … there when the Russians arrived on April 22nd, 1945. Twice the Americans sent convoys to evacuate us and both times the Soviets refused to let us go. Most American Kriegies ‘escaped.’ We were guarded only loosely and they didn’t seem to care if we walked off on our own. They wanted to exchange us for Russian PWs liberated by the Allies and who didn’t want to return to Mother Russia.”

On April 23, Capt. Watts mentioned that “the Russians are way beyond us with their spearheads and are at Potsdam (outside Berlin). Only isolated pockets of goons are left around here and they are being liquidated. Our positions are now secure.”

He reported further that the Russians took over the camp on April 23 and sent in several cattle, pigs, and butter. A Russian repatriation group of 13 officers, 20 women and 200 men, arrived on April 28. The Russian group started interviewing the POWs and wanted their names. The POWs mistrusted them.

General Ruge returned to the camp on April 25. Some POWs went into Luckenwalde town and took radios. The BBC reported that the Russians had made it to the Elbe to link up with the Americans. By April 28, a Russian mayor was installed in Luckenwalde.

Bradford said, “GI trucks in today with bread and K rations. 22 ambulances evacuated the lazarette (those in isolation because of illness).”

Watts noted on May 6 that the Russians were maintaining control,

“(The) Russians stop all movement with armed guards and send trucks back empty. Within two hours they had manned the guard towers and were shooting just in front of people trying to flee the camp for the nearby woods. You could cut the gloom with a knife.”

Bradford underscored this point, saying,

“Started out late this AM (May 5) with Takacs (Lt. Zoltan Takacs captured in North Africa) and 13 GIs with a wagon with 2 horse teams to take off, but gave it up. Russian patrols were turning everyone back.

“The Russians really got serious at this point and put armed guards on the perimeter of the camp, particularly where the wire had been breached. They had no intention of letting anyone out without orders from Moscow, evidently. A lot of rumors floating; everyone very antsy.”

Lt. Rathbone reported that the POWs began heading to American lines until the Russians realized the camp population was decreasing. He said the Russians “went out and recaptured us and herded us back to the camp so they could make a big show of turning us over to the American forces on May 21st.

Bradford said on May 6, “Evacuation (only partial) done against Russian wishes. Had to sneak out of camp, evade the armed sentries and walk 2 km to trucks. (Lt.) Takacs and I made it on the third try.”

On May 8 Watts, Lt. George Ellis, and Lt. Col. Orton got up early and boarded trucks that took them to the west. Watts said on May 8,

“Ellis, got an order signed by a drunken Russian Field Marshal who was visiting a forward division CP. Our pass clears us through the MPs (military police) who were keeping the main road clear for repatriation of thousands of Russian POWs coming back from the American zone … We reach the Elbe at Magdeburg … get the attention of the Americans on the other bank and await them sending boats across to us … We cross the river at 2130 to the 1st Bn, 117th Infantry of the 30th Division. It was quite a fight to get here, brother it was sure worth it! Fed and bedded down in Magdeburg. Had a shot of cognac.”

On May 9, Watts attended church services in Magdeburg and commented, “It is a real pleasure to see American efficiency after the goons and Russians.” On May 12, Watts flew to Le Havre and then traveled by truck to Camp Lucky Strike.

Lts. Bradford and Takacs made it to American lines, got a ride on an American truck, and by truck and train made it to Camp Lucky Strike.

A note on Camp Lucky Strike. It was one of several camps at the Le Havre Port of Entry near Normandy, France. The National Museum of WWII described it this way,

“As the war in Europe came to a close, staging camps previously used for replacements coming into the European theater did an about-face. In the summer of 1945, Camp Lucky Strike in St. Valery, France, 45 miles from the port of Le Havre, became a massive tent city for American troops preparing to embark on the voyage home. Demobilization in Western Europe was carried out primarily through Camp Lucky Strike and nine other camps, eight in France and one in Belgium. These holding areas took their code names from brands of popular cigarettes, hence they became known as the ‘cigarette camps.’ Camp Lucky Strike was the largest cigarette camp, with a capacity of 58,000 troops awaiting transportation back to the United States. Camp Lucky Strike was designated ‘RAMP Camp No. 1’ and was the chief assembly point for newly-liberated American prisoners of war, or RAMPs (Recovered American Military Personnel.)”

__________

Go to Oflag 64 “Long March Out:” Part 3, Ruhnow to Moosburg

Click to zoom graphic-photo

Table of Contents

Table of Contents