DUTY, HONOR, COURAGE, RESILIANCE

Talking Proud: Service & Sacrifice

Part 1: Sczubin to Ruhnow

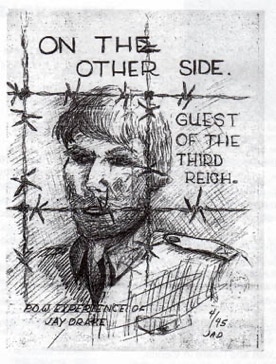

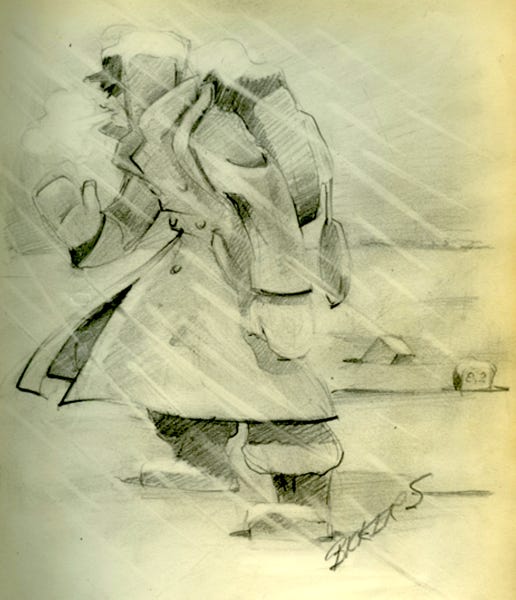

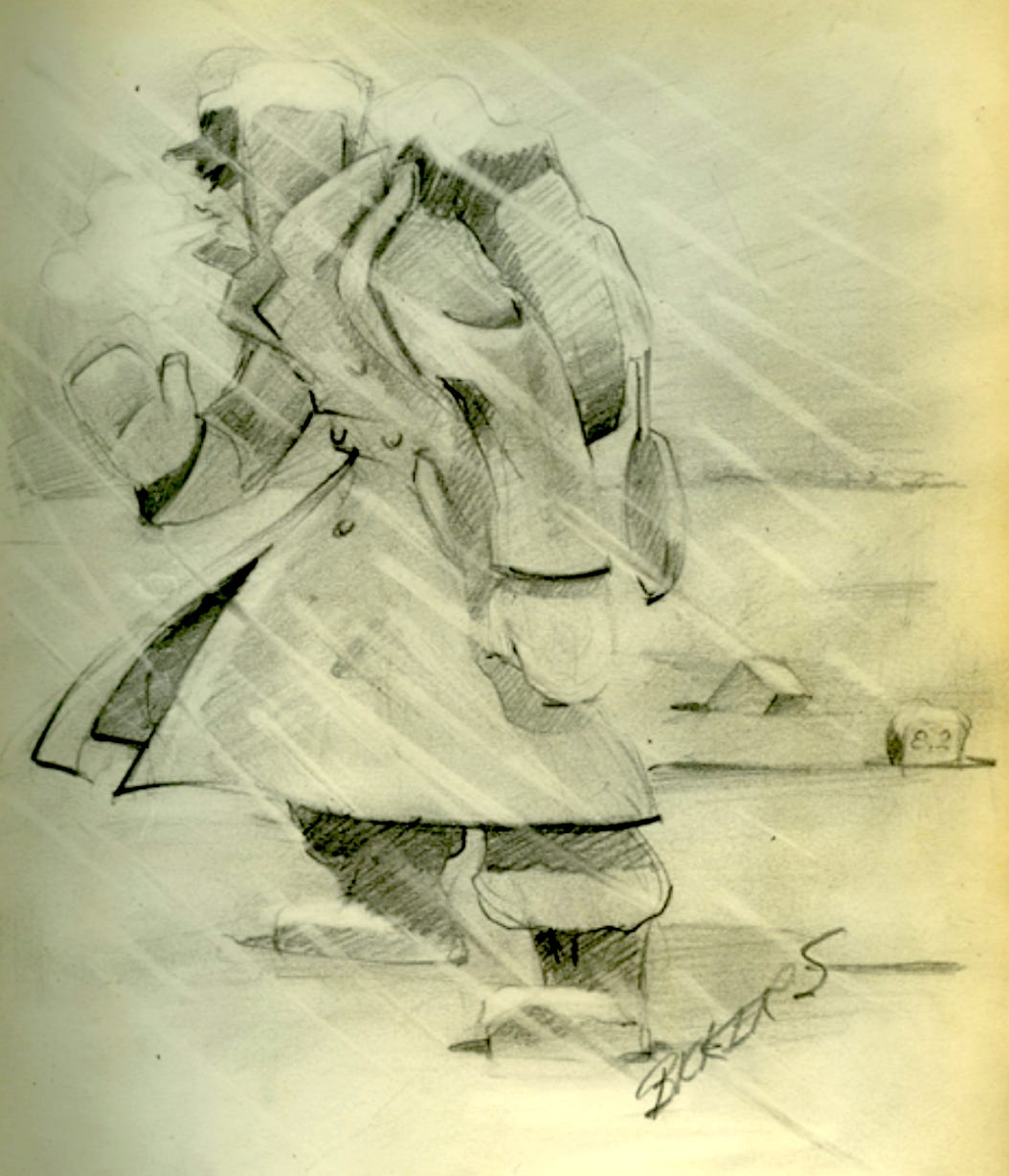

Graphic by Lt. James F. Bickers, USA, POW Oflag 64

Under the pressure of advancing Soviet forces, the Germans marched out about 1,200 POWs from Oflag 64 at Sczubin, Poland, and left some 200 sick and wounded behind, leaving them for the Russians.

An unnamed author wrote,

“The Germans moved more than 100,000 POWs of various nationalities westward away from the advancing Red Army. At least a few thousand perished in the process, some while on the march, some during their escapes. Many suffered serious health problems as a consequence.”

The men who were marched out of Oflag 64, Sczubin, Poland, by German guards were exposed to the brutal Polish winter. Winds whipped through their ragged clothing. They slogged through deep snow on rutted roads amidst fleeing refugees and often under Allied bombs. Their boots froze over. They had precious little to eat or drink. They slept in desolated barns and on packed rail boxcars. Yet, they went on.

The Kriegies at Oflag 64 knew the Russians were coming. They had a secret radio called “The Bird.” They stayed informed about Soviet advances and German defenses. Lt. Victor Kanners, 413th Infantry, would say, “Come on, You Ruskies!” That was a famous phrase in the camp. His

An unnamed author who survived wrote,

“The German war effort was collapsing, and the eastern front had disintegrated before the Russian advance. The German garrison that was guarding the nearly 2,000 American officers in Oflag 64 was increasingly apprehensive about its own safety since the foremost salient of the Russian push was aimed almost directly at our camp. Worry was evident on the faces of our captors, and their preoccupation resulted in considerable relaxation of camp routine and discipline.”

The Kriegies knew the Soviets would have to pass through Sczubin to get to Berlin, and they were closing in fast. The red dot marks the location of Oflag 64. Anticipating that a march out might be forthcoming, Colonel Goode ordered his fellow prisoners to walk a specific path inside the barbed wire enclosure for one hour every day to be in shape to leave, as told by Lt. Kanners.

Lt. Kanners was a relatively new “kriegie.” He asked a fellow POW who had been there longer why he was so excited, as Kanners was not. The POW said, “I don’t know about you, but I’m getting out of this place.”

You’ll see that getting out was one thing, obtaining freedom quite another.

For days, refugees, young and old, had been flowing to the West. Kanners called it a “procession.”

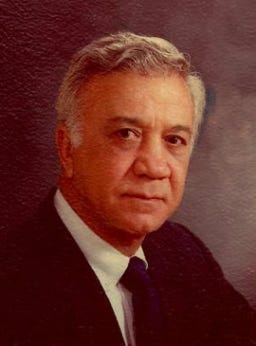

Capt. Amelio Palluconi, 505th Parachute Infantry, reported that the Germans had informed the POWs that they “would be moved back to Germany because of the Russian situation.”

On January 20, the POWs were told they would be moving out within 48 hours. Indeed, they departed the next day at 10 a.m., carrying only their Red Cross box and extra clothes. Col. Goode said he “protested the march and delayed it as much as possible.” But he lost the argument.

Toni Reavis, son of POW Lt. Isham Reavis, 362nd Infantry, reported on his website, “Wandering in a Running World,”

“Col. Paul Goode walked into one of the prison barracks of Oflag 64…at 5 p.m. on the afternoon of January 20, 1945. ‘Listen up,’ began the camp’s ranking American officer. ‘We’re moving out tomorrow. That’s all I know. So dispose of everything you don’t want to carry. Don’t bother to ask anything, this is all I can tell you. Moving west. Good luck to all of you.’”

Lt. Everett Roland Anderson, 15th Infantry, said Col. Goode “convinced the Germans to release captured Polish Army overcoats, jackets, and hats, and issue these items of clothing to the POWs.” They grabbed what they could. Goode told the men to take as much food as they had. Palluconi said he was able to “bribe the German interpreter with cigarettes and a promise of protection if overtaken by the Russians … Because of this bribe we received extra clothing, shoes, underwear, matches, etc. out of a German supply room which had to be broken into.”

Anderson referred to the march as “a march of death.”

Lt. Jay Drake, 378th field artillery, drew this illustration, appropriately reflecting what it must have felt like in the POW camp. But now he was getting out, albeit in sub-zero freezing weather and led by German guards. He commented,

“(I had) a long Polish Army overcoat, socks worn over his hands for mittens.” He said he “used long underwear bottoms for a hat, scarf, and face mask.” Like other POWs at Oflag 64, he said they used a buddy system, where each would select a buddy to help the other on the march. His buddy was Ed Lockert, infantry: “Ed was a good scrounger and a loyal buddy through the long march,” Drake said.

Col. Goode led the march out. The Russians were coming.

Lt. Drake estimated about 1,300 POWs left Oflag 64 with “150 old Latvian guards.” Col. Goode, Lt. Kanners said, "strode out of the gate and down the road with platoons following in numerical order.” Several prisoners mentioned that Col. Goode’s bagpipes led the way. Incredible. They had bagpipes stored away!

About 10 percent of the POWs were left to the Soviets, escaped the marches westward and made it to Soviet lines, or returned to the camp. I’ll discuss them in the “Lone Rangers” section.

The march out began prim and proper, according to Lt. Kanners. The POWs were formed by platoons, “of which there were 27 (50 men per platoon). He said medical men were distributed among the platoons. That would total about 1,350.

POW record-keeping in those days was not accurate. I have found it unproductive to try to get a consensus number.

Lt. Malcolm A. Baldwin, 28th Infantry, said 1,282 officers and 109 enlisted men were in the column.

Lt. Henry W. Haynes, 444th Bomb Group, opined 1,459 officers, two warrant officers, and 136 enlisted men marched out.

Several POWs have said the column was a mile long.

Kanners’ platoon was Platoon 22, Major Ernest M. Cassidy, 49th Engineers, platoon commander. It must have been a sight to see. Kanners described it.

“(He) watched the men file out in a column of fours, sleds, wagons, boxes dragging on the snow, two men carrying a long pole with their belongings tied to the center, every imaginable pack was there.” His platoon spotted “the remains of a horse-drawn wagon … and took possession of it.”

Lt. John Culler, 337th Infantry, criticized the German guards, saying, “Our guards were older and in poorer physical condition than we were. They were too old to be in the army and served to guard us.” Lt. Kanners felt they could overpower the guards if the brass had an escape plan. He thought they should have an escape plan by this time but said that Col. Goode’s instructions were “escape would be up to each man,” indicating that that was the escape plan.

According to Kanners, the Germans took a head count before marching out. He said at least ten were not in the ranks. There was a secret tunnel, and some were hiding there. Capt. Frank N. Aten, 701st Tank Destroyer, said the guards determined three POWs were missing. He did not understand how they could be three short when he and three others were in the tunnel. After six or more searches, Aten said the German Hauptmann (Captain) came to Col. Goode and said, “You have hidden the three men very well. We cannot find them, so we will have to leave without them.”

I’ll talk about Lt. Aten again in the Lone Rangers section. He became known to his fellow POWs and the Germans as “an escape artist.”

Lt. William R. Cory, 805th Tank Destroyer, was one of three or four to seal themselves in the tunnel they and others had built. It was about 25 ft. underground. Cory said Col. Drury was in the hospital but opined they had enough food and water to last two weeks and were approved to seal themselves in the tunnel. They remained in the tunnel for about 20 hours until “Col. Drury … came down and brought them out … telling them that all the German guards had left.” Drury told them they were free to leave at any time. They stayed for about five days.

Oberst (Colonel) Schneider, the German camp commandant, came along. Schneider began the festivities by talking to the POWs. The POWs made light of Oberst Schneider because he delighted in making formal announcements.

Lt. Kanners said, “The gist of Schneider’s announcement was that we were officers and he expected us to act like officers. I guess he wanted us to be good little boys.”

Lt. Peter Graffagnino, 157th Infantry, a medical doctor, described Schneider as a “portly, officious commandant” who “sped off in their small battered car, scooting and skidding past the marchers to reach the head of the column.”

Capt. Aten, who was facing a firing squad for having tried to escape four times, had choice words for Oberst Schneider: “Inflated Nazi Army officer, filled with his own ego … Mousy character.”

Drake said the Kriegies “were mingled with the rest of the refugees. There was some assemblage of order for a while, but as the day continued, the stronger men made their way to the head of the column. As long as you kept moving, you could keep from freezing.”

The weather on the day of departure was frigid, and the prisoners estimated it to be between 16 and 20 degrees below zero. The countryside was “blanketed under deep snow.” Lt. Haynes said the morning was cold, and the afternoon was very cold. Lt. Kanners estimated the snow depth to be two inches.

Lt. Graffagnino, commented,

“We were bundled up in all of the clothing we owned, layer on layer and countless variety, to the limit of what could possibly be worn, and, in addition, blanket rolls containing other possessions were slung over a neck or shoulder. … POWs are like pack rats, and everything we ever saved, accumulated, scrounged or made from scraps and empty food tins was draped on our coats or dangled from some pocket, belt or button … We were a ragged, attenuated horde straggling and shuffling along like an endless procession of decrepit refugees.”

Thus far, the picture is a large group of 1200-1300 POWs marching out of Oflag 64 in structured military formation. Lt. Kanners said that did not last very long. He said, “It was impossible to maintain a column of fours.” The road was rutted, the refugees walked in the center of the formation, the horses and wagons would stop, the men had to walk around them, it was very slippery, men stopped to adjust their packs, and sleds were tipping over. He reflected, “Before long, the column was no longer a unit marching by platoons. It became a three-to-four-mile-long line of men strung out here and bunched up there.” Some POW accounts would say it got to five miles long.

Writing about Lt. Anderson’s experiences, Norley Hall said the “countryside was in utter chaos.” Anderson said, “Refugees crowded the roads. The Germans were poorly organized and in a hurry to get away before the Russians could catch them. Train travel was entirely disrupted with nothing moving on schedule and very little moving at all.” There was a great temptation to escape, but they knew they would be hunted down by dogs and shot when found.

Throughout this march, intense cold and hunger hung over the POWs every minute of every day. Toni Reavis noted,

“As the days of marching wore on and their strength ebbed, the prisoners from Oflag 64 realized they were covering less distance with each passing day, as well seeing comrades begin to die. Food and water were in short supply, and since they were marching through open countryside, they often slept without shelter, as well.”

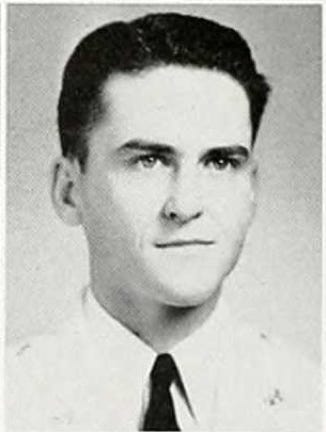

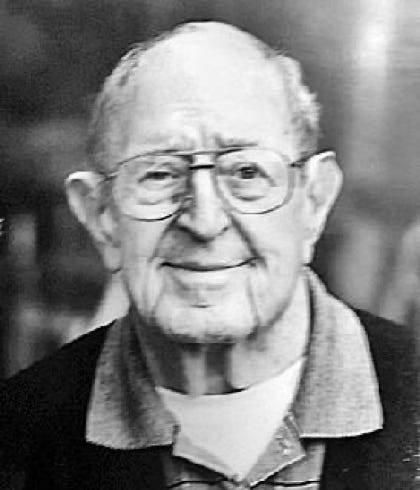

Lt. Herbert L. Garris, 377th Field Artillery, marched out (left photo). He called it a “miserable tortuous march.”

Lt. Richard H. Kellahan, 335th Infantry (right photo), said, “This forced march was the most challenging and horrible part of our POW experience because the temperature went down to minus 20 degrees in blizzard conditions, preventing any escape.”

Kellahan continued,

“The Russians were so close. All the refugees were apparently trying to get ahead of the Russians. The roads were clogged. The wagons – three of ours – people were walking by them, just getting away from the Russians, I guess. In that part of the world, the only way you could tell where the highway was by the line of trees that followed the road. Everything else was snow. And you could see these civilians headed away from the Russians. So we were traveling along with them …

“I had on two pairs of long underwear, and I had my fatigues, a field

jacket, two overcoats, two pair of long underwear, two blankets which when left camp – I brought two blankets. I had a glove and a little ribbed cap like you wear under a helmet … They wouldn’t let you keep your helmet. They just took your helmet, but you could keep your helmet liner … Thank goodness I had that …

“One pair of socks. When we’d stop at night, we would take your boots … And you take your socks off and put them under your armpits so they wouldn’t freeze. And you’d put your boots outside of you on the stall, and you’d take your blanket and your overcoat and stuff, and cover yourself up and sleep. In the mornings, of course, you could get your socks on because they had not frozen. But your shoes would be frozen and it would take a couple of hours or so of walking to get them thawed out, and they’d rarely be soft. So that’s how we operated.

“The hay barns – a lot of the guys in the morning they wouldn’t come out. They’d stay in there trying to escape, and some of them did. But the Germans caught on to that, so they would empty the straw barns and then bring in machine guns and just riddle the hay barn with the machine gun to try to discourage people from trying to bury themselves in there to get away. So that put a pretty good stop to that, and there was no getting away.”

Reavis talked about how the Kriegies would buddy up to help each other on the long march. He said,

“Nobody lays down tonight. Honest, lay down here you will never get back up again. You’ll die. That’s all there is to it. So we’ll just take turns. I’ll hold you so you can sleep. And when I can’t hold you any longer, you’ll hold me.”

On the first day, the column stopped at a “large Polish dairy farm operated … by Baron von Rosen, an Oberst (Colonel) in the Wehrmacht (German Army).

The POWs who remained with the group marched about 15-17 miles to Eschfield (Eichfelde or Polanowo), arriving on January 22. The Poles generally did their best to help the POWs with bread and cheese and, on occasion, more.

The ranks of the Kriegies on the march thinned by January 22. Lt. John P. Sanford, 333rd Infantry, noted dead horses were lying along the road, the guards did a lot of yelling, and he heard small arms fire nearby. The Russians were coming.

Lt. Drake felt the same: “My buddy and I, as well as the majority of the POWs, stayed as a main group, thinking it would be safer when we met the Russians.”

Lt. William Haynes said the POWs broke up into three groups: Go ahead, think they can go ahead, stay behind.

At this point, it becomes difficult to tell the story of the Kriegies of Oflag 64. A large group left the camp, leaving a small group behind. Already on Day 2, the large group starts to whittle away, the number of escapes grows, some return to Oflag 64, and the tales of dealing with the Russians and getting home get more complex. I will cover escapes in the “Lone Rangers” section.

A big day for the march occurred on January 23, the third day. The Kriegies woke up to find the German guards had gone. They immediately thought they were free. They felt they had been liberated. The senior officers told the POWs to handle the guard posts. They heard small arms and artillery fire in the distance. Local Poles whipped a ham soup over a fire after slaughtering some hogs and brought in cherry preserves. The Kriegies and Poles were singing.

Capt. Watts said the German guards left at 0400 hours. He said, “Efficiency is here again now that the Americans are in charge.”

Lt. Drake mentioned that only a German lieutenant colonel was left “for the protection of the POWs.” The others were “ordered to the rear to fight a delaying action.” Lt. Corbin said the German officer was left “in case we were accosted by German soldiers.”

Some of the POWs escaped during the absence of guards. Snipers in white garb chased after some of them by truck. Kanners and two of his buddies decided to hide, wait for the column to leave, and then high-tail it to the east. His two buddies decided hiding was a bad idea. Kanners could not win the debate, and together, all three ran after the column and re-joined it in the rear.

In his book Roads to Liberation from Oflag 64, Lt. Clarence Meltesen, 3rd Ranger, said a large group of POWs escaped from the column in Wegheim, by my calculation, about 20 miles northwest of Sczubin.

However, Lt. Frank Corbin, 3rd Ranger, said about 500 POWs escaped,. I do not know how many of them survived. Corbin reflected,

“There was no one to keep us from it. I could have taken off too but I chose to stay together because I felt that a thousand American prisoners of war would be a lot safer than walking around the countryside in Poland where I didn’t speak the language, where I didn’t know what was going to happen to me and therefore I opted to stay. My buddy, Lt. (Erin R.) Kaufman (334th Infantry) did take off and leave.”

Lt. Drake continued,

“The Germans came back about noon from the side road (and an SS company) had surrounded the area before we knew what was happening … Some of the men tried to flee to the trees and were shot in the open. Maybe five or six were lost before the inevitable was accepted.”

The POWs had about 10 hours of freedom.

As an interesting note, Kanners said someone had an American flag hidden with his stuff. The plan was to unveil it once they spotted the Russians.

It appears that Oberst Schneider tried to escape with his men back to the West, thinking the POWs were slowing him down. The SS Latvian troops, who were motorized, caught them and forced them to return to the POWs and continue the march. One SS officer went with them. The SS confiscated Schneider's car, and he was now forced to walk like everyone else.

Lt. Joseph Zelazny, 1278th Combat Engineers, commented on Schneider, saying, “Capt. Minver and Oberst Schneider tried to give up to the SAO Col. Goode before they were taken by the Russians.” Goode refused.

I’ll mention here that the first Soviets arrived at Oflag 64 in Sczubin on this date, January 23, 1945, just two days after the POWs were forced to march out. Recall that some men, as many as 200, were left behind because of illnesses and weakness. I’ll discuss them in the Lone Ranger section.

Doc. Graffagnino said the temperature was about 30 degrees below zero, adding, "We were isolated in a vast expanse of winter wasteland in the middle of nowhere."

Graffagnino said that the brief taste of freedom caused some POWs to pick fights with the guards, and the feeling was they could overpower them. However, the consensus was that the end was near; they had come a long distance and needed to hold together. Some of the POWs would not listen, and the next day, they had to leave a handful of wounded and some dead (shot) POWs behind.

On Day 4, the Germans finally gave them something to eat, some pea soup. The weather remained cold, and the ground was covered with snow. They marched to Lobsens (Lobzenica), where Poles, ignoring a Gestapo presence, provided them bread and cheese.

Lt. Kanners said the “column literally dissolved into the alleys, doorways, and stairways. The townspeople gave us most all that they had in the way of a fast bite to eat, and everyone enjoyed a brief interlude of genuine hospitality.” He also commented that when they prepared to sack out for the night, they could start fires for the first time to keep themselves warm.

The SS in the town strutted around, flaunting their "power," and tried to hold back the locals. The old guards from Sczubin rejoined the group, and 17 POWs who had earlier tried to escape were caught and returned. Kanners mentioned that he and some others met up with Oberst Schneider, who had the gall to scold them for trying to escape and for not behaving like officers, even after he, Schneider, had tried to flee his post.

On Day 5, now January 25, the Germans got more generous and provided the POWs with some bread, margarine, cheese, and hot oatmeal. That said, the Germans checked possible POW hideouts in the barns by shooting them up with their machine guns. It was on Day 5 that they would enter Germany, as the borders were then drawn, following a march of about 13 miles to the town of Flatow (Zlotow). Gun and artillery fire could still be heard in the east. The group saw Russian and British POWs in a nearby barn.

The Kriegies were now heading in a northwesterly direction toward the Baltic Sea. Lt. Sanford estimated they had marched about 48 miles.

Day 6, January 26, was their first day of rest. The Germans informed the prisoners that the Soviets had declared war against the US and Britain. Kanners said that Schneider told them that Russia had recalled her ambassadors from London and Washington. This is worth noting. The Germans were trying to set the stage for the Americans to believe that the Soviets were their enemies. The Germans would later ask the Americans to help them fight the Soviets. Kanners said the POWs weren't much involved in the US-Russia-UK issue but instead focused on getting food.

On Day 7, now January 27, they marched 12 miles to Jastrow (Jastrowie). The map shows that they had crossed into Germany and were headed northwest toward the Baltic Sea—the green dot on the lower right marks Warsaw. The Soviets moved against Warsaw in mid-January 1945.

On Day 7, the Kriegies encountered large columns of English, French, and Russian POWs. The Yanks slipped them some cigarettes as they passed by the resting Allied columns. For several days, Sandford described the marching column as better organized, perhaps because the men were finally getting some food.

The weather became a significant issue on Day 8, January 28. Most prisoners' shoes were frozen, and they faced deep snow drifts and windy plains. Sandford described the land as "snow-swept tundra." They covered 11-12 miles that day and slept in a schoolhouse at Zeppenow (Sypniewo). Fortunately, the schoolhouse had a wood-burning stove, and they found enough wood to dry out their shoes and socks. Sandford said he slept in a church. Kanners said many had to stand out in the cold for over an hour until they found places to sleep.

Kanners remarked while describing his being in Zeppenow,

“There was no prior planning or coordination for this trip, and if there had been, the swift changing situation would have thrown it out of balance anyhow. As a result, we were being housed on a catch as catch can basis, and fed the same way.”

In reading the recollections of the POWs, one point becomes patently clear. The POWs had to fend for themselves and take care of themselves despite the fact they were under German guard. It is remarkable how they came up with food, such as it was, even coffee, and how they interacted with local citizens.

I learned a new word: “Ersatz.” Merriam-Webster defines Ersatz as a "substitute.” The word was frequently applied as “an adjective to modify terms like coffee (made from acorns) and flour (made from potatoes)—ersatz products necessitated by the privations of war.” The POWs frequently referred to ersatz tea and ersatz coffee.

The National Library of Medicine addresses ersatz during WWII,

“Ersatz concoctions were developed to stretch or replace rations when coffee was scarce, including the boiling of the taproots of chicory, soybeans, barley, and grains as a potable dark liquid. Some soldiers mixed roasted grains (such as barley or acorns) with molasses, and if available, chicory and dried fruits.”

On Day 9, January 29, Dr. Graffagnino said the column of POWs was down to 800. They walked through weather and terrain similar to what they had faced the previous days, through the Westhofen German barracks, which seemed half deserted. They stayed at Oflag II-D at Grossborn in Pomerania, also known as Camp Rederitz-Westfalenhof (Nadazyce), as shown here. The Germans had just evacuated their captive Polish officers from this camp. They covered only six miles that day.

Once again, the Kriegies found coal to keep themselves warm. Sandford noted on this day that only 766 men were left out of the nearly 1500 that started, not much different from Graffagnino's report. This means they had lost 40-50 percent by this time. Some escaped. Some were left behind ill, and others were dead, either from disease or German guns. Thus far, they had walked about 75 miles in terrible weather conditions with limited rest and food.

The German colonel said the Russians had just captured Jastrow, and they would have to move out. Jastrow was about 15 miles east of Oflaf II-D. This meant the Soviets had crossed the border, as then drawn, and were now inside Germany. That was true. By the end of the month, the Soviets had reached the Oder River (the traditional border between Poland and Germany), and advanced units had started crossing into Germany proper. To some POWs, this meant it would get more challenging to escape. Many wondered where the Germans would set up their defensive lines and what would happen once they did.

Sandford said the Germans were scared to death of being taken by the Russians. Many reports had reached them of life for German POWs in Soviet camps. They had good reason to fear the Soviets; plus, they knew what the Germans had done to the Soviets during their invasion of the USSR. They knew the Soviets would seek revenge.

Oberst Schneider said fresh German forces had been brought in to thwart the Soviet advance and offered the prisoners the "opportunity" to fight against the Russians. They refused. After eating, they marched seven to nine miles, mostly at night, making it to Machlin (Machliny) on January 30.

While the Kriegies on the march ostensibly refused to fight with the Soviets, some who had escaped agreed to do just that, which I will address in the Lone Ranger section.

After being fed on January 31, Day 11, they marched toward Templeburg (Czaplinek). Rumors started flying that they would catch a train there. That was a rumor, and they stayed in barns near the town. A German farmer fed them milk, noodles, and potatoes. In Templeburg, the Kriegies were housed in groups of about 100 over a three-mile area.

Capt. Watts said he was housed in a barn near the town. His feet were in bad shape. He said, “My ankles are swollen so badly that I cannot bend them in the normal walking movement. I can only lace my boots in every second or third hole.” They got a five-minute break every two hours of walking. He said his group was “down to 700-800 men out of the 1,400 that left originally.”

It's a bit hard to synchronize the POWs’ stories, but right about now, on February 5, 1945, the column broke up into at least two sections. As far as I can tell, one group went to Luckenwald, south-southwest of Berlin, and the other went to Hammelburg, east of Frankfurt but in northern Bavaria.

I’ll first discuss the group that went to Luckenwald. Templeburg (Czaplinek) was about 30 miles east of Ruhnow, which had a train station. As you will see, the Luckenwald group was taken by truck to the Ruhnow station.

Thus far, the Oflag 64 long march had covered about 130 miles northwest toward the Baltic Sea. The column started with about 1,200 POWs and was now at about 800. Some escaped, some were left behind from illness and weakness, hopefully liberated by the Soviets; some tried to escape and were killed, and some escaped to Allied lines.

The Soviets were hot on their heels. However, viewed broadly, the Soviets stopped their advance on January 31, 1945, to regroup, reorganize, and resupply. Furthermore, the Yalta Conference between US President Roosevelt, British Prime Minister Churchill, and Soviet Premier Stalin was held in Crimea from February 4 through February 11, 1945. The Allied leaders knew an Allied victory in Europe was inevitable and made important decisions regarding the future progress of the war and the postwar world.

__________

Go to Oflag 64 “Long March Out:” Part 2, Ruhnow to Luckenwald

Click to zoom graphic-photo

Table of Contents

- Overview

- Part 1: Sczubin to Ruhnow

- Part 2: Ruhnow to Luckenwald

- Part 3: Sczubin to Moosburg

Table of Contents

Table of Contents

Table of Contents