DUTY, HONOR, COURAGE, RESILIANCE

Talking Proud: Service & Sacrifice

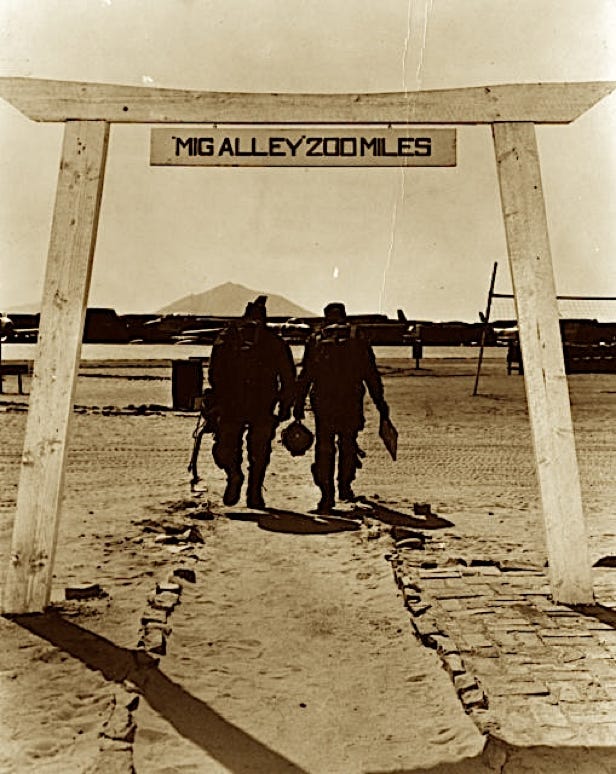

MiG Alley - Part One

INTRODUCTION

As a kid, I recall hearing the Buffalo, NY radio station talk about how many MiG-kills our F-86 Sabre jets achieved every day, maybe even a few times a day. I remember getting a huge charge from hearing how great the F-86 was against the MiG-15. It was the dawn of the jet age.

However, I didn’t know why the F-86s were fighting the MiGs in a place the radio announcer called “MiG Alley.” I didn’t realize where MiG Alley was or why it was there. I did not even know our B-29 bombers and other fighter aircraft were also scoring MiG kills.

Years later, I joined the Air Force. I served one year at Osan Air Base (AB), about 30 miles south of Seoul and 60 miles from the Demilitarized Zone (DMZ). I also served on the staff of the commander-in-chief, Pacific Command (CINCPAC) and traveled to Korea several times with some “high-priced help.” As a result, I was exposed to some heavy hitters on the Korean Peninsula.

On one trip, we visited with General Richard G. Stilwell, USA. His responsibilities at the time were reflected in his title: Commander UN Command (UNC), Commander US Forces Korea (USFK), and Commander 8th US Army. I sat across from General Stilwell, the junior officer in the room. During the conversations, I felt like General Stilwell occasionally stared at me. I could not figure out why.

General Stilwell approached me as the dialogs wound down and said, “Capt. Marek, that’s a Czech name?” I said, “No sir, it’s Polish.” He smiled broadly, “Ah yes, Polish.” I sensed he was slightly disappointed in himself, so I said, “Yes, sir, but in Czech, the name Marek is often used as a boy’s first name, Mark.” He smiled again and said something like, “Of course.” He shook my hand, and we left. I later learned General Stilwell was also from Buffalo, NY, my hometown. I wish I had known that. He might have invited me for dinner!

I have long taken a keen interest in Korea and the Korean War of 1950-1953. MiG Alley has always been on my mind. While stationed at Osan, we knew that modern-day jet aircraft could target us within five minutes of crossing the DMZ. During inspections, USAF F-4s would overfly our site, and our rib cages would rattle from their sounds, the “Sounds of Freedom,” as we called them. The inspector was testing our reactions.

I have researched MiG Alley and learned a lot about it and the Korean War. The ground and air war complexities and the many tradeoffs have stirred me. I have also taken note of the North Korean-Chinese-Soviet interactions that affected the war, as well as the politics of the Truman administration. Finally, I have been astounded by how the American leadership strung together the forces at hand to fight, something like “baling wire and bubblegum,” as we used to say. My heart often pumps with a flutter when I think of the men who fought during this pasted-together war.

President Harry Truman called it a UN Police Action. Hogwash, I say. It was a no-kidding-around war.

Robert Frank Futrell, a senior historian, wrote “The United States Air Force in Korea 1950-1953,” originally published in 1961 and revised in 1983 and 1991. I have drawn from it. I have also drawn from US Army History, which offers a detailed blow-by-blow account of ground operations from start to finish. I will link portions of it that I used. Finally, I wish to tip my hat to Javier Guerrero, who has assembled a chronology of the B-29 campaign in the Korean War. I will draw from it as well.

A lot has been written about MiG Alley. When I started this endeavor, I thought MiG Alley was a story about USAF B-29 bombers, Soviet MiG-15 jet fighters, and USAF F-86 Sabre jet fighters in aerial combat over northwestern North Korean airspace. It was much more than that. Believe it or not, the WWII P-51 Mustang, a propeller-driven fighter, the F-82 Twin Mustang, the F-80C Shooting Star, and the F-84 Thunderjet, the latter two jet aircraft, all went up against the Soviet MiG-15 and their Soviet pilots.

I intended to explore all four years of the war, but this proved too much for me, and I concluded it would be too much for you. So, I have chosen to pass on what I have learned that has intrigued me. That usually translates to points I did not know or did not fully appreciate. They all impact the MiG Alley Story.

The net result is that I have divided the story into two parts. Part One deals with political issues that would impact MiG Alley, and Part Two addresses the military situation and air combat.

I should start by defining MiG Alley. Wikipedia presents a good definition,

“ MiG Alley was the name given by American pilots during the Korean War to the northwestern portion of North Korea, where the Yalu River empties into the Yellow Sea. It was the site of numerous dogfights between American fighter pilots and their opponents from the Soviet Union, and later from North Korea and the People's Republic of China. Soviet-built Mikoyan-Gurevich MiG-15 were the aircraft used during most of the conflict, and the area's nickname was derived from them. It was the site of the first large-scale jet-vs.-jet air battles.”

Several events gave shape to MiG Alley. The dominant element shaping MiG Alley was that the Soviets, Chinese, North Koreans, and Americans wanted to obtain air superiority to command the skies over North Korea and prohibit enemy aircraft from attacking Allied ground forces and logistics lines.

- The Soviets secretly deployed a sizeable number of MiG-15 advanced air superiority jet fighters and Soviet pilots to Antung Air Base (AB), China, located on the western reach of the Yalu River, just above where it empties into Korea Bay. It lies directly opposite Sinuiju, North Korea. The Yalu River marks the boundary between the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea (DPRK), North Korea, and the People’s Republic of China (PRC). At the time of its introduction to the Korean War, it was the most capable air superiority fighter in the theater, arguably in the world.

- Allied ground forces, fighting as part of the UN Command, fought their way into northwestern DPRK and were forced to retreat from this area. They required air superiority so they were not attacked from the air. They also needed close air support while fighting on the ground and air interdiction of North Korean targets, especially logistics and transportation targets.

- North Korean and Chinese logistics lines and main supply lines ran through this region, and the Allies had to sever these lines, especially the Yalu bridges.

- The USAF’s B-29 Superfortress bomber of the kind used in A-bomb attacks in Japan was used throughout the Korean Theater, but especially in this northwest sector of the DPRK. It was a four-engine propeller-driven heavy bomber with a maximum speed of 357 mph, a cruise speed of 220 mph, a service ceiling of 31,850 ft., and a range of 5,600 miles. It carried ten remote-controller 12.7mm Browning Machine Guns, two 0.50 Browning Machine Guns, and one 20mm cannon.

What’s so great about the MiG-15?

The MiG-15 was a swept-wing, single-seat air superiority fighter, arguably the best in the world at the time. The swept wings enabled it to be transonic, approaching the speed of sound, about 0.8+ Mach. Its maximum speed was 641 mph at 16,400 ft altitude and 652 mph at sea level. It was able to accelerate rapidly, and it had an excellent rate of turn and rate of climb. Its ceiling was about 51,000 ft. Its range was about 500 miles. Its armament included a 37mm cannon system and two 23mm cannons. It entered service in late December 1948, becoming operational in 1949. In short, it was a world-class jet fighter.

However, it had flaws, most notably during a dive when it lost stability and when it suffered mid-air fuel tank implosions.

The pilots also did not have G-suits, flight suits worn by aviators subject to high acceleration forces known as “Gs.” They prevent a black-out and g-LOC (g-induced loss of consciousness) caused by the blood pooling in the lower part of the body when under acceleration, thus depriving the brain of blood.

A common question is why the Korean Peninsula is divided into the DPRK in the North and the Republic of Korea (ROK) in the South. The short answer is that the US and USSR decided this would be the case. Koreans did not like this decision.

Japan ruled Korea from 1910 to 1945. Before that, it was a protectorate of China and ruled by a succession of dynasties. Historically, outsiders, mainly Chinese and Japanese, occupied the Korean peninsula. Koreans rebelled against the Chinese and the Japanese. One might have thought that the Japanese surrender to end WWII would have offered Koreans their freedom. Not so.

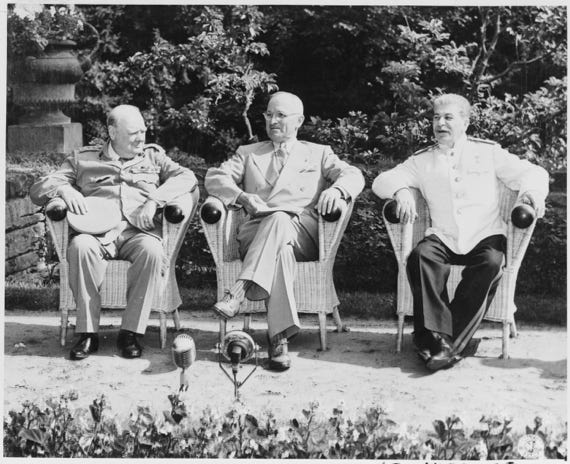

The US, USSR, and British leaders met in February 1945 at the Yalta Conference to discuss the way forward during and after WWII. The war ended in May 1945 in Europe and September 1945 in the Pacific.

James Matray, emeritus professor of history, wrote in the Journal of American-East Asian Relations that US President Roosevelt and Soviet leader Stalin agreed at Yalta to establish a four-power trusteeship for Korea: US, USSR, Britain, and China (the Republic of China-ROC ruled by Generalissimo Chiang Kai-shek). Theoretically, the objective was to pave the way for an independent Korea.

FDR died in April 1945. President Truman and Stalin avoided discussing the future of Korea at the Potsdam Conference of July-August 1945, effectively letting this four-power trusteeship dither.

Stalin entered WWII in the Pacific at the 11th hour, on August 8, 1945, between the US bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. The US did not like this Soviet intrusion because all hands knew the Soviets would seize as much territory as they could when Japan surrendered. That’s what they did in Korea and the Kurile Island chain.

On August 13, 1945, the US Joint Chiefs of Staff (JCS) appointed General Douglas MacArthur, USA, to receive the Japanese surrender.

The plot thickened in mid-August 1945. US officials decided that there would be two zones of occupation of Korea, the US and Soviet, divided at the 38th parallel. Michael Fry said in National Geographic that Colonel Dean Rusk and Colonel Charles “Tic” Bonesteel “were assigned the task of identifying a line of control that both the US and Soviets could agree to.” That was the 38th parallel. It would separate the US and Soviet occupation zones.

The US JCS confirmed that decision, and the Soviets agreed as well. That slammed the door shut on the four-power trusteeship.

During WWII, Kim Koo led a Korean Provisional Government in Chungking, China. Dr. Syngman Rhee was its representative in the US. When Japan surrendered on September 2, 1945, the Provisional Government of Korea (PRK) was organized based on earlier work done during August to establish local committees throughout the peninsula to prepare for Korean independence. The US arranged for the provisional government members to return to Korea in late September 1945.

When the Soviets entered Pyongyang on August 24, 1945, they identified the People’s Committee there and quickly plugged the top positions with those friendly to the Soviet Union. Kim Il Sung became the leader in Pyongyang.

General MacArthur selected Lt. General John R. Hodge, commander of the US Army XXIV Corps, to occupy Korea. This corps participated in the invasion of Okinawa and came to Korea from there. The codename assigned to the US occupation of Korea was “Operation Blacklist Forty.” It involved 45,000 US troops. MacArthur warned Hodge that the Soviets might already be in Seoul; if so, Hodge was to take over Seoul nonetheless.

General Hodge established the US Army Military Government in Korea (USAMGIK) when he arrived. However, the US was not prepared to govern southern Korea. In October 1945, Hodge created the Korean Advisory Council and appointed members favorable to the US.

General MacArthur had his hands full with the American occupation of Japan. He told the Korean people on September 7 that the US was establishing military control over all of Korea south of the 38th Parallel. The proclamation said,

"Having in mind the long enslavement of the people of Korea and the determination that in due course Korea shall become free and independent, the Korean people are assured that the purpose of the occupation is to enforce the Instrument of Surrender (of Japan) and to protect them in their personal and religious rights. In giving effect to these purposes, your active aid and compliance are required.... All persons will obey promptly all my orders and orders issued under my authority. Acts of resistance to the occupying forces or any acts which may disturb public peace and safety will be punished severely."

General Hodge appointed Maj. Gen. Archibald V. Arnold, commander of the U.S. 7th Division, the initial occupation force, as the Military Governor of South Korea on September 12, 1945. The State Department tasked Mr. H. Merrell Benninghoff as General Arnold’s political advisor. On September 15, Benninghoff complained to the State Department that they had no information on US policy toward Korea as it looked divided, and the staff was far too small, with too few competent people.

Thus, the history of foreign occupation of the Korean peninsula continued after WWII. This time, the occupiers were the Soviets in the North and the Americans in the South.

On October 17, 1945, MacArthur received a directive from Washington about US policy toward Korea,

“(The) ultimate objective (was) to foster conditions which will bring about the establishment of a free and independent nation capable of taking her place as a responsible and peaceful member of the family of nations. In all your activities you will bear in mind the policy of the United States in regard to Korea, which contemplates a progressive development from this initial interim period of civil affairs administration by the United States and the U.S.S.R., to a period of trusteeship under the United States, the United Kingdom, China (ROC), and the U.S.S.R., and finally to the eventual independence of Korea with membership in the United Nations organization."

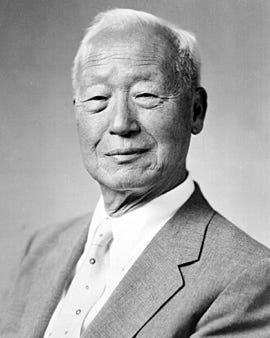

So, the four-power trusteeship was back on the table. But not for long. Messrs. Kim Il-Sung (left) and Syngman Rhee (right) arrived in mid-October 1945.

The Moscow Conference of Foreign Ministers from the US, USSR, and Britain was held in December 1945. It called for a joint US-USSR commission drawn from the commands (I interpret military commands) from the South and the North.

This commission was to “assist in the formation of a provisional Korean government.” The commission was then to present its proposals for setting up that government to the four-power trusteeship. The US and USSR would have to make the “final decision.”

Once the provisional government was formed, the Joint Commission would consult with it and provide its proposals for a four-power trusteeship for Korea for up to five years.

US and Soviet officials met from January 16, 1946, to February 5. The US position was to integrate the two zones, while the Soviets wanted them to stay separate. General Hodge reported that the two zones could not be reunited unless the entire peninsula was communist. The Soviets launched a propaganda campaign asserting the US was preventing Korean unification and independence.

By October, the Soviets withdrew from the Joint Commission, and on October 11, 1946, withdrew their Russian liaison detachment from South Korea. The Soviets then introduced Kim Il Sung, and he assumed control of the Korean Communist Party in North Korea. The Interim (Provisional) People’s Committee was created on February 12, 1946.

The US military government in Tokyo brought Syngman Rhee from the US to Japan following the Japanese surrender on September 2, 1945. The State Department refused to give him a passport. The military government in Tokyo provided him with a passport and brought him back to Korea in mid-October 1945. He assumed top political positions in Seoul, opposed a trusteeship, refused to join the US-Soviet Joint Commission, and refused to negotiate with the North.

In June 1946, Rhee argued for an independent government in South Korea. After much wheeling and dealing, he became the first president of the Republic of Korea (ROK) on August 15, 1946. The North established the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea (DPRK) on September 8, 1946.

The division of Korea was complete. That is, it was complete as far as the US and USSR were concerned. This was a disaster for Koreans who had thought they would be free and independent.

Before the KPA invasion and as the war evolved, there was much wheeling and dealing behind closed doors in Moscow, Beijing, and Pyongyang. Washington also made a few defining decisions. Taken together, these deals enabled the formation of MiG Alley.

United States

Demobilize

Following WWII, the US quickly demobilized its military forces. Military manpower was short. The JCS felt the 45,000 men in Korea “could well be used elsewhere.” In 1947, the JCS saw “little strategic interest in maintaining the present troops and bases in Korea.”

The only concern was that the Soviets might establish a military base in North Korea from which they could attack Japan. The JCS was also worried about the rising disorder in Korea, which might fall on American military forces to solve. The JCS was right to have this concern.

JCS was emphatic, however, saying,

“The United States should not become so irrevocably involved in the Korean situation that any action taken by any faction in Korea or by any other power in Korea could be considered a casus belli for the US.”

The ROK was established on August 15, 1948. Syngman Rhee became its first president. The JCS opined that this meant “the US military government in Korea came to an end.”

The plan was to begin withdrawing US military forces from the ROK on August 15, 1948, and complete the withdrawal by December 15, 1948. But that was delayed. The State Department felt it was too soon after the ROK was established. A new deadline of January 15, 1949, was set.

Communist-inspired rebellions shook the ROK, and revolts occurred in the constabulary. President Rhee asked for further delays.

Major General John B. Coulter, USA, commander of US Army Forces Korea, said he believed an invasion from North Korea was possible in the near future. The Department of State asked for a delay. On November 15, 1948, the Army instructed MacArthur to retain one reinforced regimental combat team of no more than 7,500 men in Korea.

National Security Council (NSC) Paper 8/2, approved by Truman, stipulated that the US would withdraw all troops by June 29, 1949. However, General Omar Bradley, USA, chief of staff of the US Army, was concerned that a complete withdrawal would result in a North Korean invasion. The Army studied the issue. The JCS issued a memorandum that declared Korea was of “little strategic value to the United States.” It further said,

“Any commitment of US military force in Korea would be ill-advised, and that the introduction of an international army under UN sanction would be practicable only if the forces envisioned by Article 43 of the UN Charter were in existence.”

The last elements of US forces in Korea left on June 29, 1949. No UN force was there when the KPA invaded.

The US maintained an advisory mission called the US Military Advisory Group Korea (KMAG). General MacArthur relinquished all responsibility for Korea except for some minor KMAG support requirements.

Soviet forces were said to have withdrawn by the end of 1948.

Contain Soviet Expansionism

President Harry Truman announced what came to be known as the Truman Doctrine in a speech to a joint session of Congress on March 12, 1947. The State Department’s Historian described the doctrine,

“With the Truman Doctrine, President Harry S. Truman established that the United States would provide political, military and economic assistance to all democratic nations under threat from external or internal authoritarian forces. The Truman Doctrine effectively reoriented U.S. foreign policy, away from its usual stance of withdrawal from regional conflicts not directly involving the United States, to one of possible intervention in far away conflicts.”

Truman directed his remarks at the Soviet Union and against communist expansionism and totalitarianism into independent nations. He promoted the idea of containing Soviet expansionism, the Containment Policy. It was focused on Western Europe, Japan, and the United States. Blocking Soviet expansionism remained a central feature of US foreign policy through the Cold War.

There was a feeling that the Soviet Union was seeking world domination. Truman increased defense spending as a result. NSC 68 of April 1950 called for a significant buildup of conventional and nuclear arms that would enable the US to protect itself and its allies. It was secret until 1975. The budget was not a secret. It was there for all to see, along with the supporting justification.

In January 1950, before the KPA invasion, Truman did not discriminate between vital and peripheral national interests. This was one critique of Truman’s containment policy. The Truman administration, however, announced two important peripheral interests.

Truman announced that the US would not become involved in disputes over the Formosa Strait and would not intervene if the Chinese Communists attacked Formosa. He viewed the problem as a Chinese civil problem and did not want to get involved.

Secretary of State Dean Acheson announced in January 1950 that Korea was outside the US defense perimeter. He said the American “defensive perimeter runs along the Aleutians to Japan and then goes to the Ryukyus (south of Japan) and the Philippines. Acheson continued,

“So far as the military security of other areas in the Pacific is concerned, it must be clear that no person can guarantee these areas against military attack. But it must also be clear that such a guarantee is hardly sensible or necessary within the realm of practical relationship.

“Should such an attack occur… the initial reliance must be on the people attacked to resist it, and then upon the commitments of the entire civilized world under the Charter of the United Nations.”

North Korea, USSR, and China Join Hands

Kim Il-Sung became the leader of the DPRK in 1948. Hao Yufan and Zhai Zhihai offer insights into what was happening inside the DPRK before the outbreak of the Korean War.

Kim Il-Sung visited Joseph Stalin, the leader of the USSR, several times in 1949 and 1950 to discuss his plan to invade the ROK and unify the peninsula under his communist rule. His last visit was in April 1950. At that meeting, he provided Stalin with the details of his plan. Kim interpreted Stalin’s reluctant agreement as a green light.

Stalin was torn on what to do with Kim Il-Sung’s plan. Stalin did not want war with the US. That was an underlying source of his apprehension. The question loomed whether the US would intervene if the DPRK invaded.

Shin Bok-ryong, writing “The Origins of the Korean War,” said Stalin was worried the US and Japan would intervene if Kim invaded. Kim himself was worried about this.

“Stalin asked Kim to be prudent in opening the war and asked to keep himself away from a military clash on the 38th Parallel.

“Despite this, J. Stalin believed Kim’s opinion that because the U.S. had withdrawn its army from Korea, they were not obliged to obey the regulation on the 38th Parallel. Furthermore, that if they could take victory on the first strike, the U.S. would have no time to intervene, ensuring Stalin and Kim would win the game.

“Stalin did not know whether Kim Il-Sung would march southward (of Seoul) or stop … In our (Stalin’s) opinion, the attack absolutely must continue, and the sooner South Korea is liberated, the less chance there is for intervention.”

According to Stephen Tootle, “(Stalin) was convinced the United States would not defend South Korea,” in part because “U.S. Secretary of State Dean Acheson had announced publicly in January 1950 that South Korea was outside the American defense perimeter,” also in part due to the US not intervening when the Communists evicted the Nationalists from mainland China to Formosa.

Of note is that Shin Bok-ryong contended that Stalin did not want any Soviet-supplied arms to fall into the hands of the Americans. Stalin ordered that “the Americans should not know that Russians had been involved in this war.”

I’ll switch quickly to Mao Zedong, the new Chinese Communist leader. Kim also told Mao of his concepts but did not provide details.

Yufan and Zhihai contend the KPA invasion of the ROK surprised China as much as it did the US. The Chinese, like the US, had demobilized. Furthermore, like Stalin, Mao feared another world war, this time with the US.

Mao had just finished a long and bloody civil war with the nationalists after having fought the Japanese. That said, Mao agreed with Stalin that the US would not intervene. Nonetheless, Shin Bok-ryong wrote that Mao had doubts about Kim’s plan, saying,

“Mao, at first, expressed considerable skepticism when Kim told him that Stalin had reassessed the North’s potential for a successful assault on the South.”

On the other hand, Bok-ryong said, “From May 13 through May 16, especially, Kim relied upon the commitment to support North Korea from Mao Tse-tung, who, in a change from his previous mindset, believed the war in Korea a fait accompli.”

Steven J. Zalaga, a writer focused mainly on the Soviet military, has said,

“(Stalin) once promised Mao that the USSR would handle the air war … (and) he offered to give China more MiG-15s and to provide limited direct air support … The Chinese Air Force … hoped to win sufficient control of the air to permit bomber and attack regiments of the CPVAF (Chinese People’s Volunteer Air Force) to conduct close air support missions for Chinese forces during its spring offensive.”

Zhang Xiaoming, an Associate Professor of History at Texas A&M International

University has written about the Chinese Air Plan and its relationship to the Soviets. He maintains that Stalin failed to provide direct ground support to Chinese forces on the ground during their October 1950 invasion. The Chinese leadership noted, however, that the PLA invasion proceeded well without such support.

Before the KPA invasion, Truman announced that the US would not become involved in disputes over the Formosa Strait and would not intervene if the CHICOMs attacked Formosa. He viewed the problem as a Chinese civil problem and did not want to get involved. Secretary of State Acheson had also announced that Korea was outside the US defense perimeter. As a result, Mao was willing to take some chances on Korea.

Truman throws the communists a curveball.

President Truman met with his security advisors on the evening of June 25 (Washington time), 1950, the day of the KPA invasion. Despite all previous American foreign policy pronouncements, he directed a few actions in response.

Truman declared the Formosa Strait neutral and sent the US 7th Fleet there to prevent any outbreak of hostilities in Korea, in effect putting Formosa under US protection. Preventing China from invading Formosa was a worry, but the US was also worried that Chinese Nationalist leader Chiang Kai-shek might invade the mainland. The US intended to prevent that.

With regard to Korea, Truman ordered the use of air power to cover the evacuation of US citizens and destroy KPA tanks if necessary. He would soon authorize the introduction of US combat forces.

Truman voiced his concerns about Korea escalating to a war with the USSR. James I. Matray quoted Truman saying to his advisors,

“We must be damn careful. We must not say that we are anticipating a war with the Soviet Union. We want to take any steps we have to push the North Koreans behind the line … but I don’t want to get us over-committed to a whole lot of other things that could mean war.”

Matray also noted that Truman agreed with Secretary of State Acheson’s “opinion that Moscow did not want a direct military clash with the United States in Korea, stating prophetically that ‘the Russians are going to let the Chinese do the fighting for them.’”

On the evening of June 29, the JCS authorized General MacArthur to employ “such army combat and service forces to insure the retention of a port and air base in the general area of Pusan-Chinhae.” On June 30, Truman approved MacArthur’s request to deploy one Regimental Combat Team and two divisions to Korea.

Truman insisted the Korean War be seen as a UN, not a US war. General MacArthur was to be viewed as a UN commander, and his command was to be known as the UN Command, UNC. Truman did this to reduce the risk that it would evolve into a US vs. China-Soviet WWIII.

That said, by June 30, 1950, President Truman had authorized the use of air forces against the KPA, the use of the US 7th Fleet against the DPRK, and the deployment of significant ground forces to Korea. The UN Security Council did not approve the creation of a UN Command and appointment of a US military officer to lead that command until July 7, 1950. Truman had acted on his own.

Furthermore, the direction for the war’s conduct came from Washington and MacArthur himself, who often acted alone. General MacArthur ordered the execution of military operations. There was precious little UN command and control involvement.

At this point, Truman, Stalin, and Mao all wanted to avoid war with the other. Stalin and Mao felt the US would not intervene. Within hours of the KPA invasion, the US intervened.

Click to zoom graphic-photo