DUTY, HONOR, COURAGE, RESILIANCE

Talking Proud: Service & Sacrifice

MiG Alley - Part Two

The KPA pulled off a stunning invasion of the ROK on June 25, 1950, sending from 70,000-90,000 troops against an ill-prepared ROK Army (ROKA) at a time when there were no US ground combat forces in the ROK.

The 8th US Army was on occupation duties in Japan following WWII. Its four Army divisions were the closest to Korea but were not combat-ready. The 8th Army commander, Lt. General Walton “Johnny” Walker, sent three of his four divisions to the ROK piecemeal as fast as possible. They started arriving in mid-July.

The Korean peninsula is roughly 500 miles from top to bottom. It is remarkable how fast-moving the Korean War was.

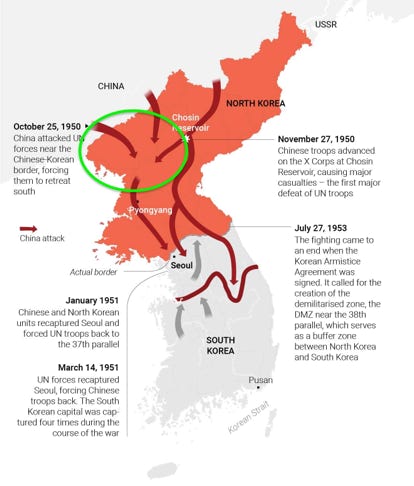

By early August, invading KPA forces pushed the US 8th Army’s three divisions and the remnants of the ROKA to below the Naktong River around Pusan in southeastern ROK, which came to be known as the Pusan Perimeter. The Naktong was a natural barrier, and the Allied forces held for six weeks of fierce fighting. The KPA could not break through.

US forces did an end-run to the northwest and landed at Inchon near Seoul on September 16. Those in the Pusan Perimeter broke out on September 18 and battled across the 38th parallel border into North Korea and to the Yalu River border with China. The 8th Army X Corps withdrew from Inchon and swept around the east side of the peninsula, landed at Wonsan, and moved north toward the Yalu. Allied forces reached the Yalu in the east and within about 40 miles of the Yalu in the west in October.

China started sending its PLA troops into the DPRK in mid-October, launched attacks against Allied positions in late October, and pushed the Allies to positions along the Ch'ongch'on River. They then conducted a frontal assault along the breadth of Allied positions from November 25 to December 2, 1950. This region from the Yalu to the Ch'ongch'on roughly defined MiG Alley. Allied ground forces stalled and fell below the river.

Army History says,

“The battles along the Ch’ongch’on River were a major defeat for the Eighth Army and a mortal blow to the hopes of MacArthur and others for the reunification of Korea by force of arms.”

General Walker ordered the 8th Army to leave North Korea and retreat below the 38th parallel. His forces retreated to below the 37th parallel, conducted a series of offensives, and fought back to the 38th, where a stalemate ensued.

I’ll stop this segment here.

Throughout these ordeals, Allied ground forces needed close air support and interdiction of critical targets to offset the superior numbers of enemy forces. They required that support on their way up the peninsula on offense, on their way down in retreat, and during the stalemate.

Until November 1950, the US had air superiority in the skies of Korea. Stalin promised air support, and he delivered. The secret introduction of the Soviet MiG-15 in China challenged US air superiority, which put Allied ground forces in grave danger.

Many USAF, Navy, and Marine, fighter and bomber aircraft, operated throughout the Korean peninsula, supporting ground troops, interdicting logistics, and transportation lines, and fighting against the MiG-15.

This was the USAF’s first shooting war. The USAF was established in 1947 and was mainly drawn from the Army Air Corps, which fought in WWII.

At the time of the KPA invasion, most USAF combat aircraft were in Japan, Guam, or the US. The Far East Air Forces (FEAF), headquartered in Tokyo, Japan, controlled most of these combat aircraft. General Hoyt Vandenberg, the USAF chief of staff, called FEAF “the shoestring Air Force.” It employed a variety of piston and jet-powered aircraft.

Robert Frank Futrell, a senior historian who wrote “The United States Air Force in Korea 1950-1953,” noted that senior military leaders felt the hodgepodge of fighter and bomber aircraft they had would be enough. To its credit, FEAF was able to patch together operations and aircraft mixes to provide air support to ground forces and maintain air superiority. Therefore, the “shoestring Air Force” in place appeared good enough.

Lt. General George Stratemeyer, USAF, commanded the FEAF in Tokyo. Major General Earle Partridge, USAF, commander, 5th AF, was located at Yokota AB, Japan, near Tokyo. It was subordinate to FEAF. Major General Ralph Stearly commanded the 20th AF in Guam.

On July 8, 1950, FEAF organized FEAF Bomber Command (Provisional) at Yokota. Major General Emmett O’Donnell Jr. commanded the FEAF Bomber Command. The 20th AF was assigned to it.

The Bomber Command was created for the B-29 Stratofortress heavy bomber, which conducted missions over Korea from Japan and Okinawa. There were two kinds of B-29s. One was assigned to the Strategic Air Command (SAC), earmarked for nuclear attacks against the USSR. This category included most B-29s. The other kind of B-29 was assigned to a numbered air force for use in situations like Korea. The creation of FEAF Bomber Command (Provisional) enabled consolidated tactical control of all B-29s conducting missions in Korea.

The newly formed USAF had about 1,172 aircraft in the Pacific region at the time of the invasion. Let’s briefly look at this “shoestring Air Force.”

During the initial weeks of the war, the F-80C Shooting Star jet fighter mainly flew air superiority missions staging from Itazuke Air Base (AB) on Kyushu, the southernmost island of Japan’s home islands. Itazuke was the closest FEAF airfield to Korea at the outbreak of hostilities.

The F-80C ruled the skies in the early days of the war. It then became a main ground attack fighter, primarily low-level rocket, bomb, and napalm attacks. It later deployed to Suwon AB, ROK, about 20 miles south of Seoul.

The F-51 Mustang piston-powered aircraft was a stalwart fighter in WWII and had good range. The USAF had plenty of F-51Ds in storage and service when the Korean War began, and many were shipped to Korea via aircraft carriers. The USAF and ROK Air Force (ROKAF) flew them. At first, planners thought the F-51 could handle the air-to-air job but quickly switched it to ground attack. They started their combat flying from Japan and could hit targets not within the range of the F-80C. The Royal Australian Air Force and South African Air Force also flew them.

F-82 Twin Mustang fighters were being phased out, but 45 were at Naha AB, Okinawa, Itazuke AB, and Johnson AB, Japan. They were designed for long-range bomber escort and would play a vital role in the early days of the war. The F-82s flew out of Itazuke AB, could fly their missions, loiter over Korea, and return when needed. They scored the first aerial victory for the USAF, shooting down a propeller-driven North Korean Air Force (NKAF) Yak-11.

The B-26 Invaders, about 26 of them, were based at Iwakuni AB, on Honshu, the main island of Japan. They began their missions from there, limiting their time over target, but in 1951, they moved to Kunsan AB and Pusan in the ROK. They bombed marshaling yards captured in the ROK by the KPA on June 28, 1950, three days after the war started, and then on June 29, they bombed Pyongyang, North Korea’s capital. More B-26s were sent to conduct bombing and reconnaissance missions, and they ended up as main night bombers. They were the only aircraft suitable for night bombing at the time. Convoys were their primary targets.

The B-29 Superfortress was the aircraft used to drop the A-bombs on Japan. She was a centerpiece of the MiG Alley fight. The first B-29s were deployed from Guam to Kadena AB, Okinawa, Japan, then to Yokota AB, and Ashiya AB in Kyushu, Japan, striking targets of opportunity such as railroad bridges, tanks, trucks, and concentrations of enemy troops. By July, they were authorized to attack strategic targets in North Korea, such as chemical plants, oil refineries, marshaling yards, docks, and critical bridges.

That was the shoestring Air Force FEAF had to cobble together. Two important “latecomers,” the F-84 Thunderjet and F-86 Sabre, arrived in Japan on November 30, 1950, both jet aircraft. The F-84 flew from Taegu AB in the ROK in December 1950. It excelled as a close air support and daytime interdiction strike aircraft. The F-86 flew from Kimpo Airfield outside Seoul and later from Suwon, about 30 miles south of Seoul. It was an air-to-air superiority fighter. More on these two later.

I should mention the USN F9F Panther was the Navy’s first jet-powered fighter to enter combat. The AD-5 Propeller-driven Skyraider dive bomber was a Navy and Marine standout.

The North Korean Air Force (NKAF) Yak fighters and IL-10 piston-engine attack planes were no match for the “shoestring Air Force.” USAF and USN aircraft ruled the skies until the secret arrival of the Soviet MiG-15 in August 1950, and then the first MiG-15 engagements with US aircraft in November 1950.

Let’s quickly review the situation on the ground through November 1950.

- The KPA invaded on June 25, 1950.

- They captured Seoul on June 29.

- They forced Allied ground forces south to the Pusan Perimeter in southeastern ROK.

- The Allies fought the KPA at the Pusan Perimeter roughly six weeks from August 4 to September 18, 1950.

- The KPA was unable to push the Allies back.

- The Allies did an end run and attacked Inchon near Seoul on September 16.

- Allied forces broke out of the Perimeter on September 18 and started their movement northward.

- The Allies crossed the 38th parallel on October 1 through October 9, 1950.

- The Allies entered Pyongyang, the DPRK capital, on October 19.

- Chinese forces People’s Liberation Army (PLA) began crossing the Yalu River to enter the DPRK in mid-October.

- The PLA launched its First Phase Offensive on October 25.

- On November 1, 1950, the Allies retreated to an area around the Chongchon River where an intense battle would ensue.

When thinking of the B-29 in Korea, it will serve you well to imagine how the ground war proceeded.

• The KPA pushed Allied ground forces to the south of Korea.

• The Allies fought all the way north to the Yalu.

• The Chinese invaded and forced Allied ground forces southward.

The B-29 interdicted key strategic targets in the DPRK, provided direct air support to ground forces in the fight, and, in a few instances, shot down attacking enemy aircraft.

Robert Frank Futrell, a senior historian writing “The United States Air Force in Korea 1950-1953,” provides an in-depth look at USAF air operations throughout the Korean War. I will draw from it. I also will draw from Robert Dorr’s book, B-29 Superfortress Units of the Korean War.

To start, air operations were to support and assist in the defense of the ROK. Later, the objective was to reunify the Korean peninsula under a government favorable to the US.

The HistoryNet noted,

“As the ground situation worsened for the retreating South Korean forces, Truman authorized MacArthur to expand airstrikes north of the 38th parallel against North Korean supply depots, railyards and supporting strategic targets.”

At the time, there was only one bombardment group (BG) in the world whose B-29s were not assigned to SAC and were stationed overseas. That was the 19th BG of the 20th AF in Guam. Guam’s B-29s were also closest to Korea.

Bud Farrell has written,

“That the 19th (BG) was not in SAC made it special … a Ragamuffin outfit on the far end and outside of the SAC supply chain, with apparent low priority for access to anything, particularly uniforms and flight gear such as flight Jackets, flying fatigues (those cool suits with all the zippered pockets), and aircraft maintenance equipment and spare parts … the Sad Sack Orphans of the FEAF (Far East Air Force), the 19th took a special pride in being an ‘odd man out’!”

The 19th BG was the first B-29 group to arrive and the last to leave the war.

The 19th BG promptly began bombing on June 28 against targets such as bridges, roads, railroads, and troop concentrations when they could be found. The initial job was to provide defensive protection for Allied ground forces retreating to the south and to cover the evacuation of Americans from Seoul.

Dorr wrote that Truman “distrusted airmen,” seeing them as “glamour boys” flying needlessly expensive aircraft. The USAF had plenty of “glamour boys” perhaps, but the USAF was the only service that could put iron on the target right away.

Javier Guerrero has assembled a chronology of the B-29 campaign in the Korean War. I will draw from it.

On June 29, 1950, the Joint Chiefs of Staff (JCS) issued orders to MacArthur,

“You are authorized to extend your operations into Northern Korea against air bases, depots, tank farms, troop columns and other such purely military targets, if and when, in your judgment, this becomes essential for the performance of your missions.”

However, the JCS issued a note of caution,

“The decision to commit United States … does not constitute a decision to engage in war with the Soviet Union if Soviet forces intervene in Korea … If Soviet forces actively oppose our operations in Korea, your forces should defend themselves, should take no action to aggravate the situation, and you should report the situation to Washington.”

Truman also authorized American ground forces on this date, agreeing to deploy one Regimental Combat Team and two Army divisions drawn from troops on occupation duty in Japan.

On July 6, 1950, nine B-29s from the 19th BG bombed an “oil refinery in Wonson and a chemical plant in Hungnam, both located in North Korea … They targeted North Korean units in Wonju, Pyongtaek, and Chunchon (in South Korea), achieving favorable results.”

On July 12, a Yak jumped a 19th BG B-29 from behind, damaged it, and it crashed in the Yellow Sea. One crew was taken prisoner while the rest were rescued.

In the first two months, the 19th BG flew more than six hundred sorties, supporting UN ground forces by bombing enemy troops, vehicles, and such communications points as the Han River bridges.

Four more bomb groups came to Japan. Each one had belonged to SAC but was detached temporarily to fly for the Far East Air Forces Bomber Command (Provisional).

The 92nd BG deployed to Yokota AB in July 1950 and immediately began bombing the Wonson Marshalling Yards. It fell under the 20th AF but returned to the US in late October and November 1950.

The 22nd Bomb Group also arrived from SAC in July 1950 and was assigned to Kadena AB under the 20th AF. Wikipedia says, “On 13 July, the group flew its first mission against the marshaling yards and oil refinery at Wonsan, North Korea.”

The 98th BG followed in August 1950 and deployed to Yokota AB. It immediately started bombing marshaling yards at Pyongyang, quickly becoming an important part of the interdiction effort. It had previously fallen under SAC’s command.

The 307th BG then arrived at Kadena AB from McDill AFB, Florida, in August. From August through September 1950, the 307th bombed strategic targets in North Korea. Once again, these were drawn from SAC.

Guerrero summed up the B-29’s missions in the early days of the war,

“During the month of August, the B-29 Superfortresses launched bombing missions against marshaling yards and industrial sites in North Korea, as well as port facilities and bridges in both North and South Korea, with a particular emphasis on those in the vicinity of Seoul. Additionally, they carried out massive carpet-bombing raids close to the front line …

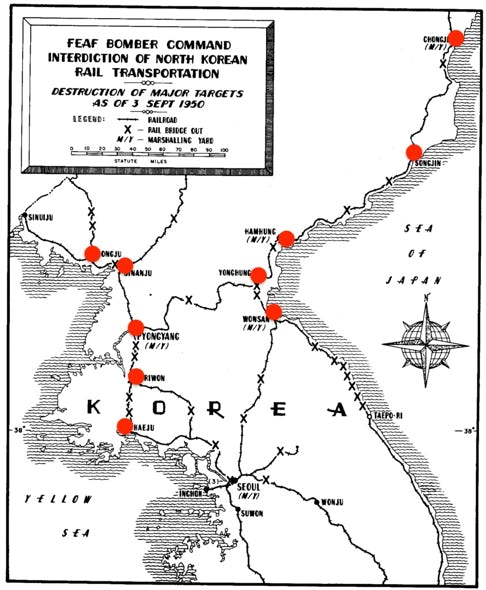

“(In September 1950, a) major B-29 bombing campaign (was conducted) targeting industrial facilities and troop training centers in cities like Wonsan, Hungnam, Hamhung, Pyongyang, Songjin, and Chongjin in North Korea. Additionally, B-29s conducted bombing missions on marshaling yards and railroad junctions in North Korea and provided close air support to the Eighth Army in South Korea.”

Several of these bomb runs came close to China and the USSR.

By September 15, 1950, the B-29s had destroyed nearly all 18 strategic targets in North Korea.

Anti-aircraft guns on the Chinese side of the Yalu River attacked an RB-29 conducting reconnaissance along the border. This may have been a significant warning shot of warfare to come.

On September 1, MacArthur instructed General Stratemeyer to support the troops fighting in the Pusan Perimeter. Many missions were launched to attack KPA targets assaulting Allied forces in the Perimeter. On September 18, forty-two B-29s conducted saturation bombing to clear a path for the 8th Army Pusan breakout.

After six weeks of heart-wrenching, fierce combat, Allied forces in the Perimeter did an end run and attacked Inchon close to Seoul and then broke out of the Perimeter to head northward.

Having destroyed most strategic targets in the DPRK, the 22nd and 92nd BGs were recalled to the US in October. The remaining B-29s focused on tactical targets supporting forces on the ground. The B-29 missions also started attacking the bridges across the Yalu River.

Between June and November 1950, the B-29s bombed where they pleased virtually at will. Some called the flights “milk runs.” The B-29s did not encounter significant enemy fighter opposition, though many encountered technical problems, and some crashed.

I’ll pause the discussion of the B-29s here. Their lives were about to get more complicated.

The shape of MiG Alley started to form when the Soviets sent a detachment of the 50th IAD to Antung Airfield on the western Yalu River in August 1950. The 50th IAD MiG-15s came with experienced Soviet pilots. The Soviets did this in secret under strict Soviet control. The Soviets set up a three-nation (USSR-DPRK-PRC) command center at Antung, and the Soviets were in charge. North Koreans and Chinese were there to learn and provide cover for the Soviets.

John T. Correll, the editor of Air Force Magazine, wrote:

“In August 1950, a Soviet air division with 122 MiG-15 jet fighters arrived in northeastern China and were based at Antung (Dadong) on the Yalu River, the dividing line between Chinese Manchuria and North Korea.”

Ralph Wetterhahn has written,

“What U.S. pilots didn’t know was that every MiG flown in North Korea between November 1950 and December 1951 had a Soviet pilot at the controls.”

Mitch Williamson, a technical writer interested in military affairs, writing “Korea 1950 Soviet Pilots Enter the Fighting,” has said at first the Soviet role was to,

“Defend critical targets in the PDRK (DPRK) … First and foremost, the 151st IAD was to protect the strategically important bridge across the Yalu not far from Andong (Antung), as well as Andong itself, in which there were supplies and CPV (PLA) units, which were using this bridge to move into North Korea.”

Writing for history.com, David Roos said Joseph Stalin “had promised Soviet air support to Mao (Zedong) as part of their alliance. (Samuel) Wells says that Stalin dragged his feet but eventually committed a dozen regiments of Soviet MiG-15 fighter jets to defend the Chinese-Korean border.”

Recall how squeamish Stalin was about getting into a war with the US. The Soviet introduction of the MiG-15 at Antung was done in secret. Using Soviet pilots to fly them was also in secret.

Recall that Stalin felt he could provide the Chinese with equipment but left the fighting to the Chinese. He was quite apprehensive about the Soviets facing US forces in combat. In the case of Korea, Stalin cloaked the MiG-15s, and Soviet pilots were sent to Antung as either North Koreans or Chinese. The National Museum of the USAF has said this,

“The Soviets tried to hide their nationality and denied they had pilots in direct combat. Their MiG-15s had North Korean or Chinese markings. Soviet pilots received orders to only speak Korean phrases over the radio (although F-86 pilots heard them speaking Russian over the radio in the heat of combat). Despite these precautions, USAF pilots reported seeing non-Asian pilots flying the MiGs. Sabre pilots also noticed the difference in experience when less-skilled North Korean and Chinese pilots also began flying MiG-15s against them -- they nicknamed the more-capable Soviet pilots ‘Honchos’ (Japanese for ‘boss’). The fact that Soviet pilots were flying the MiGs became an open secret.

“Antung, just across the Yalu River border in Manchuria, was the main MiG-15 base. The communists built additional MiG bases in the area, which together with the original base became known as the ‘Antung Complex.’ Since it was in China, the rules of engagement prevented UN forces from bombing it.

“The secondary MiG-15 bases in Anshan, Liaoyang, Mukden and other areas in China provided places to rotate MiG-15 units out of combat, and after a rest, allowed them to be sent back quickly to Antung.”

The Soviets and Chinese referred to these bases in China as “in the rear.” This will become an issue later, so keep it in mind.

The shape of MiG Alley took even more form as Allied ground forces moved northward after the Pusan breakout. This ground force movement began in mid-September 1950 and extended through mid-October 1950 when they started approaching the Yalu River and the Chinese border.

In some respects, we have a real cloak-and-dagger effort here among the Soviets, Chinese Communists, and North Koreans.

Between August and November, the Soviets trained and conducted area familiarization with their MiG-15s.

Samuel J. Cox, Director of Naval History and Heritage Command, has written,

“On 30 September 1950, an F-4U-4B Corsair pilot of Fighter Squadron VF-113 off Philippine Sea (CV-47) sighted a MiG-15 swept-wing jet fighter northwest of Seoul.”

Robert F. Dorr, in his book B-29 Superfortress Units of the Korean War, wrote,

“An RB-29 reconnaissance crew of the 31st Strategic Reconnaissance Squadron (SRS) peered across the Yalu River and counted more than 75 fighters parked in neat rows at Antung airfield. We know today that these were MiG-15s belonging to a Soviet fighter regiment. The fighters were gone the following day, and General Stratmeyer concluded that the enemy had merely displayed the aircraft as ‘window dressing.’”

Stratmeyer was wrong.

Dorr reported on Gene Fisher, a 30th Bomb Squadron (BS) gunner from the 19th BG. Fisher’s comments went like this:

“The first time I spotted a MiG-15 was on the 23 October 1950 mission, a seven-and-a-half-hour marathon to the bridges along the Yalu River. We could see the Manchurian air bases on the other side of the border (Yalu River). We could see the MiGs taking off. When they made passes at us, I could see their noses lighting up.”

Other crews also saw the MiG-15s. One airman reported watching a MiG-15 limping across the Yalu with trailing smoke. Still, the US leadership seemed unconvinced about the MiGs and their threat.

John Correll, in his article “MiG Alley,” wrote,

“The Fifth Air Force quickly realized that the MiG pilots were not Chinese or Koreans. They were Russians. The Americans caught sight of some of them. Ground-air communications exposed the Soviet’s Achilles heel. The Soviets insisted on using ground-controlled authorities (GCA) to direct the MiG-15s by radio. US intelligence overheard these radio transmissions. The Russians attempted to communicate, as ordered, in Chinese or Korean but reverted to Russian in the heat of battle.”

Samuel J. Cox said on October 31, 1950, a USAF F-80 sighted “silver, arrow-shaped jets over Antung airfield.”

USAF and USN fighter and bomber aircraft operated in northwestern DPRK to support Allied ground forces moving into and away from this area and attack supply routes running through the area.

The MiGs cross over and engage

The situation for Allied ground forces in November and December 1950 following the Chinese invasion was grim. The challenge to US air superiority reared its head with the introduction of the MiG-15 and its seasoned Soviet pilots.

The MiG-15’s mission was to destroy B-29s since the B-29 presented a nuclear bombing threat to the Soviet Union. The MiG-15 was among the best air superiority aircraft in the world at the time, if not the best. The Korean War offered the Soviets the chance to test their MiG-15 against the B-29 in an environment less than an all-out war with the US. The B-29 carried eight .50-cal. Machine guns in remote-controlled turrets plus two .50-cal. machine guns and one 20mm cannon in the tail.

The MiG-15's swept wing enabled it to achieve historic speeds. Its maximum speed was 641 mph at 16,400 ft altitude and 652 mph at sea level. The cruising speed for a B-29 was about 220 mph, with a maximum speed of 357 mph. And, of course, it was a big, lumbering, propeller-driven aircraft. Nonetheless, the B-29 crews were able to put up some defense.

The Soviets brought their MiG-15s out of hiding on November 1, 1950, to challenge US aircraft flying in northwestern DPRK. My view is they created MiG Alley. There was a lot of action in the Alley as the Soviet MiGs piloted by Soviets came out to challenge the US. It was a full day.

According to Robert F. Futrell, in the morning of November 1, 1950, three Yak fighters, I assume Sinuiji Yak-11s, attacked a Mosquito forward air control (FAC) T-6 aircraft and a B-26 Marauder about 15 miles south of Sinuiji. He said the B-26 shot down one Yak. Two F-51s arrived and shot down the other two Yaks.

Futrell highlights an interesting fact: Yak aircraft staged out of Sinuiji airfield and were parked in revetments that opened toward the Yalu. That would make it more difficult to attack them in their revetments. To line up for a jet fighter attack on the enemy aircraft in the revetment would risk overflying China and expose the F-80C to hostile AAA fire from the Chinese side of the Yalu.

Eight MiG-15s attacked fifteen F-51 Mustangs and a Mosquito T-6 operating against Sinuiju on November 1, 1950. Futrell said that this encounter was without result. A Mosquito T-6 reported once he got to his base, which at the time was Pyongyang, the DPRK capital, that it was a MiG-15 that attacked.

However, Mitch Williamson, a technical writer interested in military affairs, has said,

“Six MiG-15s spotted and attacked four F-51s (in the morning), but with a sharp maneuver the Mustangs evaded the attack and departed the area at tree-top level. In essence there was no combat, because the enemy declined it.”

Williamson then wrote that five MiGs patrolling the Antung area in the afternoon spotted three F-51s in the area of Naamsi-dong, opened fire, and damaged one, after which the F-51 fled the scene, possibly leaving two F-51s still in the area. He then said a different pair of MiGs attacked these two F-51s and shot one down.

The website Pacific Wrecks said a MiG-15 did shoot down an F-51 flown by Lt. Aaron Abercombrie, USAF. The American Battle Monuments Commission reported only that Lt. Abercombrie went MIA. The website HonorStates said Lt. Abercrombie was on temporary duty with a tactical control party on the ground near the Chosin Reservoir when he was ambushed and killed.

I think the latter report is true, and there is a mixup, perhaps over-reliance on Soviet reports.

In another air battle on November 1, Williamson reported three MiGs on their way back to Antung spotted 10 F-80Cs and attacked a flight of four. The Russians maintain they shot one down. The Americans reported losing an F-80C to enemy AAA fire on this date.

Again, Pacific Wrecks said the F-80C “piloted by Frank Van Sickle” was shot down by a MiG-15. The Defense POW/MIA Accounting Agency said an F-80C piloted by Major Frank Louis Van Sickle, Jr. was attacking the Sinuiju airfield, was damaged by AAA fire, and crashed, most likely killing the pilot.

The net result from my perspective is that the Soviets say their MiGs shot down two USAF aircraft, an F-51 and F-80C, both operating in the same general area in northwest DPRK on November 1. The USAF has said it lost only one F-80C to AAA fire from the ground.

It was a busy day.

General Stratemeyer, the FEAF commander, had long suspected Soviets might be involved at the Antung, China base, though he could not be sure. In a previous section, I said an RB-29 crew counted more than 75 fighters parked in neat rows at Antung Airfield on October 18, 1950. Robert F. Dorr, in his book B-29 Superfortress Units of the Korean War, wrote, “The fighters were gone the following day, and General Stratmeyer concluded that the enemy had merely displayed the aircraft as ‘window dressing.’”

On November 8, 1950 FEAF Bomber Command sent seventy B-29s against Sinuiju and the Yalu River bridges. F-80C and F-51s attacked AAA positions prior to the B-29s arrival. MiG-15s crossed over and attacked these American fighters. Lt. Russell Brown, flying a F-80C Shooting Star jet, was in this fight and knocked down one MiG near the Yalu, the first jet fighter to be shot down by a jet fighter.

Lt. Brown said,

“We had just completed a strafing run on Sinuiju antiaircraft positions and were climbing when we got word that enemy jets were in the area. Then we saw them across the Yalu, doing acrobatics. Suddenly they came over at about 400 miles an hour. We were doing about 300. They broke formation right in front of us at about 18,000 or 20,000 feet. They were good-looking planes—shiny and brand, spanking new.”

Brown added,

“As a matter of fact, they were doing loops and barrel rolls! I thought to myself that this has got to be a crazy war when the enemy can practice stunt flying right in front of you! Suddenly, all hell broke loose. Lt Col Stephens shouted for me to break left. An instant later two flashing silver aircraft dove at me out of the sun. As they swept by, I opened the throttle and tacked onto the tail of one of them, trying to manoeuvre into a firing position. As I tried to close on the enemy fighter, my F-80 started buffeting badly because I was exceeding 0.80 Mach. These were definitely MiGs, and I got a clear look at the communist jet as we bottomed out and it started a very fast climb back up into the sun. The aircraft had no distinguishing markings — just polished aluminum, swept wings and plenty fast!

“When the MiG ahead of me broke to the left, he made a fatal mistake. There was little doubt that he could climb faster than me, but when he turned, I cut him off and got in four good short bursts with my guns. It was difficult to tell if I had hit him for he just rolled over and headed for the deck in a steep dive. I racked my F-80 around and followed him down. My airspeed was indicating over 600 mph, but I could not close the gap! At this time, he was about 1000 ft away when I gave him another four bursts. Black smoke poured from the right side of his fuselage. I knew it was now or never, so I squeezed off one long burst. Orange flames licked back over his fuselage and, suddenly, the entire MiG exploded in mid-air. After that I don’t remember what happened, as I was too busy trying to pull out of my high-speed dive.”

The B-29s arrived after receiving heavy AAA fire from the Chinese side of the Yalu which American fighters could not attack and neutralize. The B-29s dropped their loads, burned out most of the Sinuiju area, and damaged the approaches to the bridges but did not destroy the spans. No USAF aircraft were hit.

On November 9, Lieutenant Commander William Amen, USN shot down a MiG-15 with his F9F-2B Panther jet fighter while escorting Douglas A1-D Skyraiders attacking the Yalu River bridges.

The first MiG-15 attack was against a B-29 was against the reconnaissance version, an RB-29 flying in the Sinuiju, escorted by eight F-80s on November 9, 1950. Two MiGs attacked the RB-29, hit it, and it crash-landed at Johnson AB in Japan. Five aircrew were killed in the landing.

On November 10, a flight of seven B-29s flew near the Yalu River and a MiG-15 shot down one. The crew bailed out but was captured.

Life in northwest DPRK started to change dramatically on November 1.

The Chinese invaded in October 1950. Now come the MiGs. The PLA's First and Second Phase Offensives eased Stalin’s mind. He promised to provide Soviet air cover for the Chinese forces. He did that. Soviet pilots and aircraft were already in China, at Antung. They now crossed the Rubicon and flew from Chinese air bases against USAF B-29 bombers and fighter aircraft over North Korea.

A new kind of air war was in train: the jet age. The MiG-15 was an air defense and air superiority fighter aircraft. American air superiority over Korea was now at risk.

On November 1, 1950, eight MiG-15s from Antung AB, China, crossed the Yalu into North Korea and intercepted about 15 USAF P-51 Mustangs. A Soviet-piloted MiG shot down one. Then, on that same day, another Soviet-piloted MiG-15 shot down an F-80C, a jet fighter designed for air superiority.

On November 9, two MiG-15s jumped an RB-29 while it was photographing Yalu River bridges. Eight F-80 Shooting Star fighters escorted it. Sgt. Harry Lavene, a B-29 tail-gunner, shot down one MiG-15 near Sinuiju. However, a MiG hit Lavene’s B-29 during this flight and shot out two engines on the port side. The crew made it back to Japan. However, on the final approach, the left wing stalled, and the aircraft went in, killing everyone in the forward compartment except Lavene. Lavene was the first enlisted MiG killer. This photo shows the aft section of his RB-29.

SSgt. Richard W. Fischer, a Central Fire Controller on a 307th Bombardment Wing (BW) shot down one MiG-15 near Sinuiju on November 14, 1950. Many more B-29 MiG-15 kills occurred in 1951. SMSgt. Randy R. Diboll wrote a paper, “USAF Enlisted Aerial Victories in the Korean War.” Following these two kills, Diboll said,

“Unfortunately, these losses didn’t do much to slow down the MiG attacks against the bombers. B-29s continued to return from missions against the (Yalu) bridges heavily damaged. There were even occasions when the B-29s were shot down by the MiG interceptors. No more MiGs were shot down by Americans until the F-86 Sabre was introduced in the middle of December (1950) to escort the bombers on their raids.”

William F. (Bill) Welch, an RB-29 photo reconnaissance crewmember, commented on a mission up to the Yalu to take photos of Antung airfield. He said,

“We would go up to the Yalu and shoot pictures across the river at Antung airfield where the MiGs were based. At briefing, we were told: ‘No sweat, you’re going to have a fighter escort when you get up there.’ We met our escort just north of Seoul: Three P-51s!

“When we got to high altitude and started leaving contrails, the contrails totally obscured the view-finder in the rear compartment. I couldn’t see a thing. We had never left contrails on any of our practice flights so were not aware of the problem. With some good guesswork by Sgt Franks in the bomb bay to set the interval and some superb flying by Lt. Ambrose, we got the pictures just before being jumped by MiG-15s (The left scanner had watched them with binoculars all the way from take-off).”

Welch said the P-51s went at the MiGs “head-on and kept them busy while we peeled off headed for the Yellow Sea.” Incredibly, Lt. Ambrose, the RB-29’s skipper, did a high-speed dive as an evasive action and got away with it. He would be kidded for being a frustrated fighter pilot, but he got them out.

Javier Guerrero summarized B-29 losses in November 1950.

On November 10, MiGs attacked a formation of seven B-29s near Kusong and shot down two B-29s. Crew from one of the bombers bailed out but were captured.

On November 12, thirty-two MiGs attacked F-80 escorts for B-29s attacking a Yalu River railway bridge. One B-29 was damaged and made an emergency landing at Kimpo Airfield.

Two more B-29s were heavily damaged on November 14 when fifteen MiGs attacked 18 B-29s near Sinuiju, forcing one B-29 to make an emergency landing at Kimpo.

Futrell noted that by December 1950, MiGs were all over the skies, engaging the B-29s in the Sinuiju and Sananju areas of northwest DPRK. Nonetheless, the B-29s would continue to fly their missions up in MiG Alley.

Bomber crews reported great frustration when they went up to the Yalu. They could see the MiG-15s lined up “at parade rest” on the Antung parking ramps, “basking in the sun,” as one pilot commented, yet they were not permitted to bomb Antung because it was in China.

President Truman discussed this issue with General MacArthur. MacArthur wanted to send his troops across the Yalu and wanted his aircraft to attack targets in China.

Truman rejected the idea because the Chinese and Russians had a security pact, and attacking China, Truman feared, would cause the Russians to enter the Korean War and create a world war.

Guerrero also mentioned problems when the B-29s tried to attack the Yalu River bridges,

“(B-29) bombing of enemy ports and bridges along the Yalu River was ineffective in halting the influx of Chinese troops. Even if the FEAF bombers managed to demolish all of the permanent bridges across the Yalu, the Chinese could have used pontoon bridges or crossed where the river was frozen. Since they couldn’t fly over Manchuria, the B-29s targeted the bridges by following the river’s route. Escort fighters could only fly on the Korean side of the bombers, making the Superfortresses vulnerable to enemy fighters and antiaircraft guns stationed in China. This resulted in FEAF limiting the flights in the area.”

Anti-aircraft artillery (AAA) forced the B-29s to fly above 18,000 ft. The MiG-15 could operate as high as 50,000 ft. They would then fly above the B-29s and pick the best time to attack from their rear.

By my count, in November 1950, the first month of the MiG attacks, the MiGs shot down two B-29s and seriously damaged two more, causing one to crash land in Japan and two to make an emergency landing at Kimpo Airfield.

Futrell wrote,

“The Soviet fighter’s performance rendered obsolete every American plane in the Far East … In level flight the MiG was fully 100 miles per hour faster than the F-80C and it could climb away from the old Shooting Star as if it were anchored in the sky … Low wing loading and a 5,000-pound thrust engine resulted in a plane with spectacular maneuverability and a level speed of 660 miles per hour.”

Futrell note,

“For the most part, the MiG pilots hugged the Yalu and preferred to make their attacks from high and to the rear of American planes. Seldom, if ever, did a MiG flight make more than two passes before streaking away to break off combat at the border … The MiGs took a toll of the FEAF Bomber Command’s B-29s and RB-29s.”

Recall that Stalin was adamant about not allowing Soviet equipment to fall into Allied hands, and he was determined to keep it secret that Soviet pilots were flying against the Americans. He did not want to go to war against the US.

Steven Zalaga said, “China committed the Chinese People’s Volunteer Air Force (CPVAF) to the Korean battle, eventually sending two of its new MiG-15 fighter divisions. The first Chinese combat patrols went out on December 26 (1950).” Earlier, I said Soviet pilots flew the MiG-15 against the US until December 1951. Chinese piloted MiGs might go out on combat patrol, but they were not ready to engage the US this early.

I latched on to Zalaga's statement that the CPVAF (PLAAF) had hoped to achieve air superiority to enable its bombers and fighters to attack Allied ground forces. I’m reading the tea leaves, but I suspect that China, knowing the Allies had nothing to match the MiG-15, thought they could kick Allied ground forces while they were down and retreating. I’ll address this in Part Three of this report.

I will also address the call for help from FEAF: It needed advanced fighters to contend with the MiG-15s.

Click to zoom graphic-photo