Talking Proud: Service & Sacrifice

Logistics in the Iraq War: “A Herculean feat”

“Good generals study tactics. Great generals study logistics”

“Every truck has a personality!”

Introduction

Two weeks after US and Allied forces crossed the line of departure from Kuwait to Iraq, headed for Baghdad in the Iraq War of 2003, "Operation Iraqi Freedom" (OIF), Lieutenant General John P. Abizaid, USA, Deputy Commander (Forward) of the Combined Forces Command/U.S. Central Command, observed:

“I’m certain that when the history of this campaign is written, people will look at this move that the land forces have made in this amount of time as being not only a great military accomplishment but an incredible logistics accomplishment.”

First Lieutenant Don Gomez was an infantry officer and a rifle platoon leader with the 82nd (ABN) Division in the war. He worried about resupplying his men, who had already exhausted their Meals Ready to Eat (MRE).

Good point. How does it all get there?

The short answer is logistics, an incredible logistics machine I see as a Herculean feat.

That is the focus of this story: the sustainment of troops in combat at war. I will look at the 2003 US-British invasion of Iraq, known as “Operation Iraqi Freedom” (OIF). I will only cover the first few weeks — the complexity of this is mind-boggling. And it wasn’t all rosy.

Eric Schmitt studied logistics problems during OIF and wrote,

"Tank engines sat on warehouse shelves in Kuwait with no truck drivers to take them north. Broken-down trucks were scavenged for usable parts. Artillery units cannibalized parts from captured Iraqi guns to keep their howitzers operating. Army medics foraged medical supplies from combat hospitals.''

There were many loud complaints that troops did not get what they needed.

Of course, those in the fight will always be the hardest critics. They seek perfection. And who can blame them? Their lives and their country's future are at stake.

But the troops had a point. On the one hand, the logistics systems failed on multiple counts. On the other hand, the systems and the people who operated them achieved remarkable results with grit and determination.

OIF was an invasion that had “a need for speed.” Ground forces moved fast, very fast, often at night, many times in small units, and the logistics tail had to catch up.

The men and women providing logistics support had to overcome significant complications and obstructions to keep pace with the fighting force. That's just the way it was.

My purpose here is to get a sense of the enormity of the challenge to sustain a rapidly moving ground force exposed to jaw-dropping dynamism on the battlefield. Keep the “fog of war” in mind: uncertainty, ambiguity, and incomplete information in the heat of battle.

Whatever went wrong with logistics sustainment on the battlefield in Iraq, our forces, combat and support, pressed ahead, innovated, sucked it in, fought and won. That for me is the true testament of the American in uniform — somehow, some way, they get it done. They always have.

Allied forces crossed the line of departure, also known as “the Berm,” on the Kuwait-Iraq border on March 19, 2003, one day early because reports were coming that the Iraqis were sabotaging the oilfields.

Three weeks later, the Iraqi government collapsed under the weight of the US-British invasion.

I will examine just part of the march from Kuwait northward toward Baghdad. I have limited this story to addressing Army logistics support to V Corps, and specifically to the 3rd Infantry Division (3rd ID), during the initial days of the war. The Marines have yet another incredible story that I cannot handle here.

Fundamentally, the Army V Corps reached Baghdad on the west side of the Euphrates River, and the First Marine Expeditionary Force (1st MEF) and the British went up the east side. They both arrived at about the same time.

Lt. General William Wallace, USA, commanded the V Corps, which consisted of four divisions: the 3rd ID, the 101st Airborne (ABN) Division (Air Assault), the 82nd Airborne (ABN) Division, and the 4th ID. However, the 4th ID did not arrive until later because of problems in Turkey, which I will address later.

On March 19, 2003, I estimate 60,000 troops crossed the line of departure from Kuwait into Iraq, though it might have been more.

Major General Buford C. Blount III commanded the 3rd ID. The 3rd ID consisted of five infantry regiments, four armor regiments, four artillery regiments, one cavalry regiment, one aviation brigade, one engineering brigade, a division support command, and a corps support group, on the order of 18,000 troops.

The 3rd ID was a Mechanized Division, which meant that it employed armored vehicles for combat. I’ll just give you a flavor of their equipment.

The armor regiments employed M1A1 Abrams tanks, armored personnel carriers, and infantry fighting vehicles. You can click on the photos to enlarge each sample. The artillery regiments utilized 155-mm self-propelled howitzers. The aviation brigade operated Apache attack and utility helicopters. The cavalry regiment utilized M1A1 Abrams tanks, cavalry fighting vehicles like the Hum-Vee, Stryker, and Bradley fighting vehicles, along with OH-58D Kiowa helicopters.

The point I wish to make is that the US sent a lot of men and a lot of equipment into battle. That demanded significant planning and preparation.

It is hard to pin down exactly when military planners began to prepare for an invasion of Iraq. They had already been exposed to combat preparation and execution with “Operation Desert Shield” (1990-1991), the military buildup in Saudi Arabia in response to Iraq’s invasion of Kuwait, and “Operation Desert Storm,” which was the campaign to liberate Kuwait.

Embryonic planning for Operation Iraqi Freedom (OIF) began in 1992, shortly after Desert Storm 1990-1991, when George H.W. Bush was President. A buildup of prepositioned equipment began around then. The goal was to reduce the time required to deploy and equip soldiers on the battlefield. For example, the Army maintained a heavy brigade combat team’s set of equipment in Kuwait for 12 years before OIF. "Why?" The short answer was to prepare for another war with Iraq.

In 1992, the military began conducting a series of military exercises in Kuwait involving four US Army divisions and Special Operations Forces (SOF). By 2002, when George W. Bush was President, there was no question among the troops that they were preparing for war.

One important objective of these exercises was to build a database of what might be needed to conduct warfare in this region again. Bombs and bullets were of special concern, as was fuel, arguably the dominant worry.

Jason Tangi, assigned to the 3rd ID, was told he was going on a 30-day training mission in Kuwait. He shipped out in January 2003. By mid-February, he and his colleagues figured out the training would last longer than 30 days. It then became clear this was more than a "routine training mission." While sitting on a truck telling war stories, Tangi saw this:

"All of a sudden we see headlights – and I mean miles of headlights. Suddenly we see (semi-trailer trucks) filled with ammunition, rockets, Bradley fighting vehicles and TOWs (anti-tank guided missiles) as far as the eye can see … The next day we woke up and we combat loaded. The Bradleys were stocked with enough ammo for four days of constant battle … You could see on the faces of the senior (non-commissioned officers), they had never had this kind of training before."

Then, during the first week of March 2003, his commander ordered his unit to "sit on the Iraqi border." On March 18, the commander called his unit together and Tangi remarked:

"Finally somebody asked, ‘Are we going to war?’ I’ll never forget the captain’s response, ‘Please don’t make me have to actually say it, here is the Iraqi border and here is where we are going – do you understand.” Nobody had any further questions.”

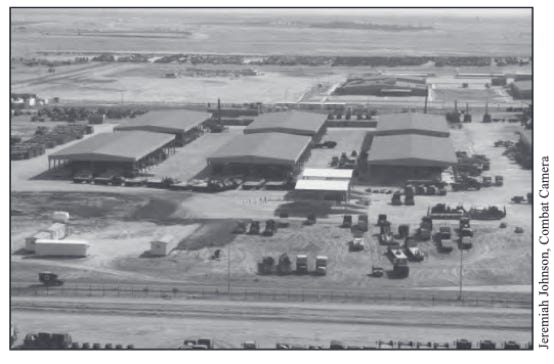

A decision was made to position three sets of equipment in the Southwest Asia Theater (SWA): Qatar, on the Persian Gulf; Camp Doha Kuwait (near the city) and Arifjan, Kuwait, on Iraq's southern border, shown here. Work began on the Qatar facility in 1995. Furthermore, equipment was prepositioned on ships, keeping the ships at sea close to potential threat areas.

On September 13, 2001, Lt. General Paul Mikolashek, commander 3rd US Army, was instructed to sketch a plan to invade Iraq’s southern oilfields and hold them. The idea was to seize everything from Umm Qasr and Basra to Nasiriyah on the Euphrates River.

In late November, 2001, Secretary of Defense (SecDef) Donald Rumsfeld ordered CENTCOM to develop a new estimate for invading Iraq and removing Saddam from power. Rumsfeld told General Tommy Franks, USA, the CENTCOM commander, he wanted surprise, speed, shock, and an early decapitation of the Iraq regime. There was quite a bit of debate, often heated. Rumsfeld insisted that the military wanted to use too many forces, and the military kept insisting that such was the need. Franks’s plan ended up with 148,000 Americans, and Rumsfeld approved that, though Franks would end up with far more, I believe around 200,000 or perhaps more. The numbers rose as the forces got closer and closer to invading.

It was clear that an armored blitzkrieg was the centerpiece of the plan. There would be a need for tactical surprise and speed. Everyone knew there was so much open conversation in the US about a pending invasion that there would be no strategic surprise, so the emphasis was placed on tactical surprise. The tactical surprise here would be a rapid set of maneuvers calculated to get to Baghdad as quickly as possible. Speed was the underlying theme.

The drive to Baghdad at a breakneck pace drove logistics planning.

Unlike Desert Storm, which evicted Iraqi forces from Kuwait, OIF would cover a lot of ground, about 400 miles. The V Corps advance was to be rapid, very rapid, avoiding cities and towns to avoid getting bogged down in fighting. The objective was Baghdad and the removal of the Iraqi government.

Planning started to firm up by mid-2002. On July 9, 2002, the chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff (CJCS) issued a planning order for possible military action against Iraq. On August 29, 2002, President G.W. Bush approved the overthrow of Saddam Hussein. CENTCOM held a war-game from October 4-5, 2002 for the overthrow of the Iraq regime.

The Military Sealift Command (MSC) maintains sea-based ships around the world loaded with prepositioned military equipment. In the summer of 2002, MSC began offloading prepositioning ships in Kuwait for Army exercises. Much of that equipment was retained in the theater for future use. Sealift began seriously in November 2002 and surged through the beginning of the war. I’ll talk more about MSC later.

Assuring there was enough fuel available to propel the advancement of forces was arguably the highest logistics priority.

In September 2002, reserve component fuel truck companies were alerted for deployment. They arrived between January and March 2003. Fuel farms were set up in northern Kuwait, and prepositioned stocks were moved from Qatar to Kuwait. The 49th Quartermaster Group (Petroleum and Water) was responsible for fuel. I’ll also address this later.

President Bush warned Saddam on March 6, 2003, that his time was running out to accept the UN process for Weapons of Mass Destruction (WMD), and he issued his final ultimatum on March 17, 2003.

The Congressional Research Service (CRS) has said about 200,000 military members were in Iraq and the surrounding area, of which about 160,000 were within the Iraq borders following the invasion. A study produced at the Army War College said after two months of fighting, about 200,000 troops were operating in Iraq.

I’ll give you a number that should draw your attention, a number you can think about when you are in your next traffic jam.

There was a six-mile wide obstacle belt at the Kuwait-Iraq border known as “the Berm.” It was built to defend Kuwait’s border and consisted of tank ditches, concertina wire, electrified fencing, and dirt berms. It was actually more than a single berm. It consisted of all that, a second berm, tank ditch, and then a third berm. The challenge was to stage and coordinate the movement of 10,000 vehicles through the berm along with many other vehicles brought by the Marine Corps. They had to breach the berm and get up to Baghdad.

A study produced at the Army War College said,

“The importance of the detailed planning of the movement through the berm cannot be overstated. This initial uncoiling would set the tone for the entire operation.”

The 3rd ID force crossed the line of departure from Kuwait into Iraq two days later, on March 19, 2003. They captured Baghdad three weeks after traveling and fighting for over 400 miles.

This report is not meant to glorify war but rather to convey a taste of what our military forces endured and achieved in the Iraq War of 2003 from a logistics perspective. It covers only the first weeks of the war, a war that lasted until 2011, some eight years. The US military lost more than 4,000 killed and 32,000 wounded.

Click to zoom graphic-photo