Talking Proud: Service & Sacrifice

Logistics in the Iraq War: “A Herculean feat”

“Good generals study tactics. Great generals study logistics”

The Saga of the 4th Infantry Division

The lieutenant had a plan, and then there was Turkey

Thus far, the thrust of the Operation Iraqi Freedom (OIF) invasion has featured the 3rd Infantry Division (ID), which came from the south, from Kuwait. The US also planned to invade Iraq from the north, from Turkey. The US wanted a two-front invasion, one from the north and one from the south, but Turkey’s parliament put the kibosh on that.

The 4th Infantry Division (4th ID), a highly mechanized, computerized heavy armor division, was selected to enter Iraq from Turkey. The deployment order was issued on January 4, 2003. It would be known as Task Force (TF) Ironhorse.

Placing a strong combat force such as the 4th ID in northern Iraq developed into an intense deployment and logistics challenge. As I always say, “Hang on, Sloopy.”

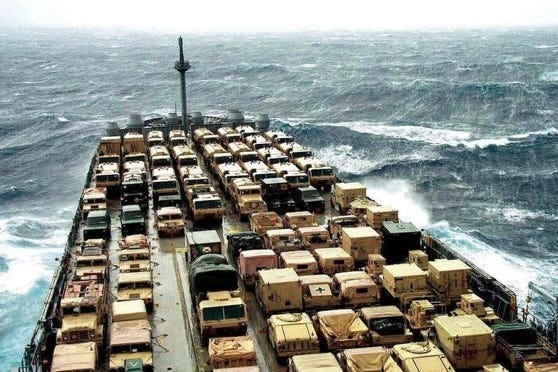

The 4th ID’s equipment, which included tanks and aircraft, was loaded onto 37 ships, maybe a few more, bound for Turkey. The ships left the US and arrived in Turkish waters. A paper published in the Army University Press said, “ Each ship was loaded with self-sustaining or partially sustaining force packages that would build operational combat power almost immediately upon arrival.”

The 4th sent a planning team to Turkey to plan for receiving the equipment. Iskenderun, just west of Syria, was to be the main port of entry in Turkey. Marines and ammunition were to be brought through Tasucu port across the Mediterranean from Cyprus. Mersin Port, a bit northeast of Tasucu, was to be used for overflow cargo. Movement Control Teams (MCT) were sent to Incirlik AB in southeast Turkey.

The Turkish Parliament voted in secret to permit the 4th ID to enter Turkey. The vote was 264-250 in favor, but it was short of an absolute majority. This vote was taken on March 1, 2003, eighteen days before the V Corps and I MEF crossed the line of departure from Kuwait. Furthermore, Turkey would not allow any combat forces to fly through its airspace into Iraq. However, it did allow logistics flights to transit its airspace and use ground routes through Turkey.

The Congressional Research Service (CRS) said Turkish public opinion opposed the 4th ID using Turkey to invade Iraq, adding that the Turkish military did not actively support it, and the president, Ahmet Necdet Sezer, said it would be unconstitutional.

The ships holding the 4th ID’s equipment sat offshore for several weeks. General Franks held the ships in place to keep Iraq focused on the 4th ID’s movements and arrival in Iraq. Anthony Cordesman said Franks "created a deception plan that helped pin down most of the 13 divisions that had deployed north of Baghdad." The 14th Movement Control Battalion (MCB) said, “The 14th MCB remained in Turkey for three months moving supplies eastward for what they thought was no reason, but what had been the plan for an attack from northern Iraq turned into a diversion to hold Iraq divisions in the north.”

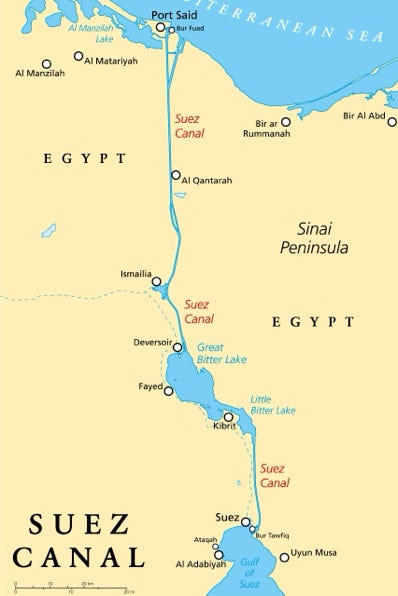

An alternate plan had been developed in case the Turkish government refused entry to US forces for the Iraq invasion. The net result was that the equipment had to sail through the Suez Canal, Arabian Sea, and Persian Gulf to Kuwait.

I should also mention that Saudi Arabia was not willing to allow the US to use its air bases and ports. This complicated the downloading of equipment in Kuwait and forced the US to establish a command and control center in Qatar instead of using the one at Sultan AB near Riyadh. Jordan also had objections.

Some 37 cargo ships carrying the 4th ID’s equipment were ordered to the Ash Shu’ayjah port in southeast Kuwait. These ships had to sail through the eastern Mediterranean Sea, the Suez Canal for the length of the Red Sea, the Gulf of Aden, the Arabian Sea, the Gulf of Oman, and the Persian Gulf. The photo shows 4 ID equipment moving by ship through the Suez Canal on March 25, 2003.

This route raised security concerns. The Suez Canal is fairly narrow and has an even narrower navigable channel. There was little room for error, and the ships were large targets if struck from land. The ships had security force protection teams on board.

The ships had to be sequenced based on the speed of each ship so the division’s equipment could move in a continuous flow. They arrived at multiple ports in Kuwait, so the download teams had to be arranged accordingly. Planning was required to ensure the troops and their equipment could fill in where and when V Corps needed them after they arrived.

The 4th ID’s troops were still in the US in three brigades: infantry, armor, field artillery, cavalry, air defense artillery, engineering, and support. The US Army Transportation Corps said, “The plan called for the deployment of over 80,000 troops through Turkey.”

Instead, the troops flew from the US to Kuwait City International Airport by air. I believe the 4th ID's strength totaled about 17,000. The USAF's Air Mobility Command (AMC) was assigned this mission. Those flights began in early April 2003. I estimate 50-60 flights by C-5/C-17/Contract Air would be needed to carry the troops to Kuwait, maybe more. The ships also arrived in early April.

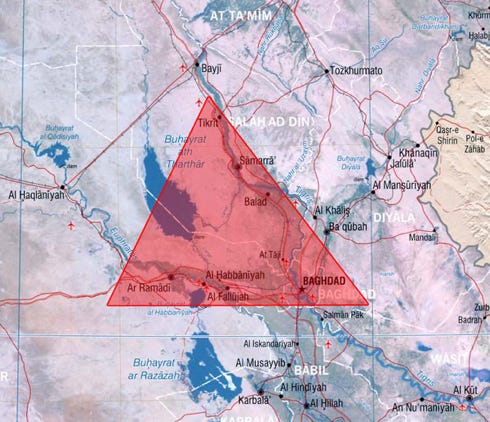

The troops moved to positions around Baghdad and then to the Sunni Triangle. This triangle was marked by Tikrit in the north, southwest to Ramadi and southeast to Baghdad. It is the most densely populated region of Iraq.

The refusal of Turkey to let the 4th ID travel through Turkey was a curve ball for the 4th ID, but also for war planning in northern Iraq. There was now an urgent requirement to open the second front in the north. Absent the 4th ID, northern Iraq had no significant friendly forces to take that task.

The 173rd Airborne Brigade was sent from Italy to northern Iraq. The plan had always been for the 173rd to join the 4th ID, but this situation differed. The 173rd BDE was airdropped into northern Iraq and the 4th ID was not there.

This decision caused a cascade of events. I divide them into two sets of events:

- Get a credible combat force into northern Iraq to hold down and defeat Iraq divisions posted there.

- Move the 4th ID into northern Iraq

Credible force into northern Iraq

The 10th Special Forces Group (Airborne) (SFG) was tasked with preparing the battlefield for the 173rd’s arrival. The Special Operations Force (SOF) force would work with Kurdish Peshmerga fighters operating inside Iraq. Bashur airfield in northeast Iraq was selected as a landing zone for the 10th SFG and the 173rd's drop zone.

Some SOF, Army, and USAF infiltrated by ground to set up infrared landing markings.

On March 21, six MC-130 special operations transports flew a battalion of the 10th SFG from Romania to a regional staging base. They were not allowed to fly through Turkish airspace. On March 22, they flew into the Bashur airfield in northeast Iraq from their staging base. The MC-130 is specially configured for SOF.

This was a perilous flight through heavy Iraqi air defenses. The MC-130s flew in at 100 ft. AGL (above ground level) and maximum speed. The lead aircraft skated through in good shape, but the Iraqis adjusted their aim when the following aircraft came through, fired just about everything they had, and several aircraft were riddled with gunfire and shrapnel holes.

Despite all the obstacles, they reached Bashur without casualties or injuries. They landed at the abandoned airfield, which the SOF secured along with the surrounding terrain. This was the longest low-level combat infiltration by US SOF since WWII.

With the SOF force in place at Bashur, on March 26, 2003, fifteen C-17 transports flying from Italy airdropped 954 troops and equipment from the 173rd BDE into an area near Bashur airfield during the night. The C-17s were permitted to fly through Turkish airspace.

John A. Tirpak reported that the first five C-17s dropped equipment and the remaining 10 dropped airborne troops. Major Andrew Robinson, USA, reported that the C-17s descended from 30,000 ft. to 1,000 ft. for the drop. The airdrop took about 25 minutes. Over the next few nights, C-17s brought in 1,200 more troops.

On March 28, two days later, C-17s brought in the 501st Forward Support Company and the 173rd’s Supply Support Activity (SSA).

The 173rd BDE, SOF, and Kurdish Peshmerga militia were now responsible for opening the second front in northern Iraq, without the 4th ID.

However, the US was concerned that the 173rd, 10th SFG, and Peshmerga would not be enough to handle Iraqi armored forces in the region. As a result, the decision was made to send the 1st BN 63rd Armor Regiment, labeled Task Force (TF) 1-63, to Bashur.

On April 7, C-17s flew troops from the 1-63rd Armor Regiment into the airfield. On April 8, C-17s brought in five Abrams tanks, five Bradley fighting vehicles, 15 armored personnel carriers, and 41 Humvees, along with other equipment. This task required 27 round-trips between Ramstein AB, Germany, and Bashur.

Altogether, SOF, 173rd BDE, 1-63 Armor, and Kurdish Peshmerga formed TF 1-63. It defeated the organized Iraqi resistance in northern Iraq by April 10.

As you might suspect, these events placed high demands on the logistics systems. The 1-63 Armor required 10,000 gallons of fuel per day. Germany's US European Command (EUCOM) handled the logistics task. Commercial carriers were hired to bring in fuel supplies. USAF Europe (USASFE) then started providing TF 1-63 sustainment stocks. Some 150 C-17 sorties and 30 C-130 sorties flew into Iraq to support TF 1-63 through May 2003.

Move the 4th ID into northern Iraq

The situation now in early April 2003 is TF 1-63 is fighting in the north, and the 4th has landed troops and equipment in Kuwait. The next challenge was to get it into position up north.

Heavy Equipment Transporters (HETs) were needed to move the division from Kuwait to Baghdad. An Army University Press paper said, “the (4th ID) staff calculated that the division needed more than 1,200 HET movements to accomplish this task.”

The 180th Transportation Battalion was tasked with commanding and controlling the movement of 4th ID equipment to its positions. HETs transported tanks and other heavy vehicles to Baghdad, then returned to the appropriate port in Kuwait, picked up another load, and returned to Baghdad. Covering the flanks was a top priority.

The 180th Transportation Battalion, "King of the Road," received the warning order to move the TF Ironhorse. It deployed to Kuwait in March 2003. Such a HET move of this magnitude had never been done before. Approximately 1,500 tracked combat vehicles and other outsized engineering equipment in the task force had to be moved. The 180th had two days to devise a plan—dynamics on the battlefield beyond imagination! Iraq’s rail infrastructure could not handle the job, so everything had to be moved by vehicle.

The 180th employed nine transportation companies, including five HET companies, two Light/Medium Truck companies, one Medium Truck Company, and one Palletized Load System (PLS) company, to move the 4th ID into position. This was the first HET battalion to be used in Iraq.

For example, on April 12, the 287th HET Company loaded M1 Abrams tanks and delivered them to Objective SAINTS outside Baghdad. Its convoy covered a 700-mile roundtrip in 72 hours. Then, it moved two armored regiments to Objective RIFLES near Fallujah in central Iraq, and the beat continued.

Once an HET was uploaded, it was put into the flow without regard for unit integrity. The vehicles first went through a maintenance “pit stop" to be checked out and given fuel, and then off they went, starting on a multi-lane highway and then going down to a single-lane road. Each HET had 40 tires, which became the biggest challenge, as more than 100 tires were needed daily. It was still early in the war, so the flow of spare parts into the theater had not matured.

Instead of being an invasion force, the 4th ID was now an occupation force, and an occupation force that met stiff Iraqi resistance over the months to come.

Sealift: The lion’s share of cargo

Click to zoom graphic-photo