DUTY, HONOR, COURAGE, RESILIANCE

Talking Proud: Service & Sacrifice

Linnie Leckrone, “the heart of a true nurse,” WWI

This story is about Miss Linnie E. Leckrone, Army Nurse Corps (ANC), WWI, at the Battle of Château-Thierry, France, in July 1918. It is also a story about the many heroines of this war, caring for so many soldiers whose daily companions were death, stench, rot, and futility. I can only give you a taste of these horrors and the supreme valor, backbone, and spirit of nurses in that war. I have a special place in my heart for nurses, all nurses.

WWI was a complicated war. It was known as the Great War to end all wars. It was a gruesome war. I have studied it several times and found that the war, especially its cause, is befuddling. It was slaughter and brutality on an unimaginable scale. This report will expose you to that in textual form.

Sir John Desmond Keegan has been known for putting a face on war. He said this about WWI,

"I constantly recall the look of disgust that passed over the face of a highly distinguished curator of one of the greatest collections of arms and armour in the world when I casually remarked to him that a common type of debris removed from the flesh of wounded men by surgeons in the gunpowder age was broken bone and teeth from neighbours in the ranks. He had simply never considered what was the effect of the weapons about which he knew so much, as artifacts, on the bodies of the soldiers who used them.

“Reticence in discussing violence is particularly unfortunate in the case of the Great War, for one important characteristic of this four-and-a-half-year conflict is its unprecedented levels of violence --- among combatants, against prisoners and, last but not least, against civilians."

WWI was one of the deadliest conflicts in history, with nearly 10 million or more worldwide having died as a result, of which about 8.5 million were military people.

Julia Catherine Stimson was the Superintendent of the Army Nurse Corps (ANC) during WWI and attained the rank of major. She has written this about the nurses in this war,

“(Nurses) at the front are having such wonderful times. They are working terribly hard, sleeping with helmets over their faces and enamel basins on their stomachs, washing in the water they had in their hot-water bags because water is so scarce, operating fourteen hours at a stretch, drinking quantities of tea because there is no coffee and nothing else to drink, wearing men’s ordnance socks under their stockings, trying to keep their feet warm in the frosty operating rooms at night, and both seeing and doing such surgical work as they never in their wildest days dreamed of, but all the time unafraid and unconcerned with the whistling, banging shells exploding around them. Oh, they are fine!”

The Allies in WWI included the British Empire, France, and the Russian Empire, which were against the Central Powers of Germany and Austria-Hungary. Italy, the US, and Japan joined the Allies, while the Ottoman Empire and Bulgaria joined the Central Powers.

There were three fronts: Western, Central, and Eastern. I will concentrate on the Western Front.

The war started in 1914. The US remained neutral for over three years, though it supplied war material to the Allies during that time. The US officially entered the war in 1917. Its force was known as the American Expeditionary Force (AEF).

Despite American neutrality, American volunteers began streaming to France in 1914 to care for wounded soldiers and refugees. Shortly after the outbreak of war, staff at the American Hospital of Paris opened a military hospital (also called an “ambulance”) to accommodate a growing number of patients returning from the Front. It was known as American Military Base Hospital No. 1, Paris.

At the outbreak of war, Mary Borden of Chicago set up a hospital unit in Dunkirk, France, in 1914. She nursed in an evacuation hospital unit just behind the front trenches in Belgium, where the staff expected 30% of the men she nursed to die. Borden was proud that the unit’s mortality rate was only 19%.

Beatrice Mary MacDonald went to France in 1915 to volunteer with the ambulance service at the American hospital in Paris. She received the Distinguished Service Cross (DSC), the second-highest military award for her service.

Ellen N. La Motte was one of the first American nurses to serve in a French field hospital during World War I. She volunteered to go in 1914 to work behind the lines. In 1916, she served in a French field hospital a few kilometers away from the front in Belgium and was confronted with the horrors of trench warfare. She saw soldiers suffering and dying for hours, days, and weeks.

The list goes on, and I should say it includes doctors, ambulance drivers, and a host of medical professionals.

The Germans were within spitting distance of Paris by September 1914. The French and British forced the Germans to fall back to a line in France west of Belgium. The net result was that both sides dug in and fought hard, back and forth, but fundamentally, the line remained relatively static. This map shows the static line, known as the trench line, running from the North Sea to Switzerland. The trench warfare in WWI lasted about three-and-a-half years, from mid-September 1914 through March 21, 1918. Neufchateau and Chateau Thierry are highlighted because Leckrone was sent to each of them.

By April 1915, American volunteer ambulance drivers had started going closer to the front lines of battle. Some Americans went to fight alongside the French on the ground and in the air as part of the Escadrille Américaine. Many carried munitions and supplies.

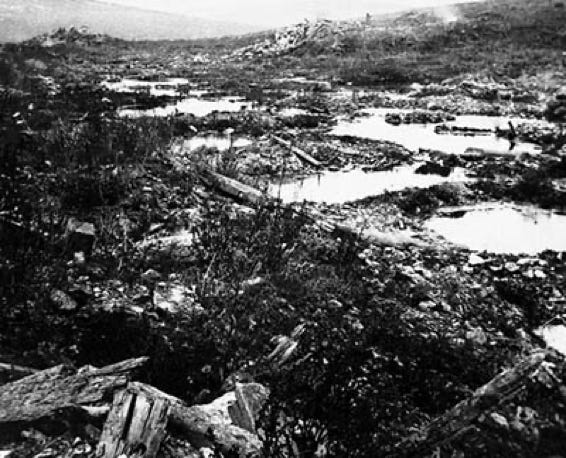

There was always a stretch of land between the two lines known as "No Man's Land," heavily struck by artillery from both sides, well within machine-gun range, and cluttered with barbed wire to impede the rush. Many men fought and died trying to rush the other side or simply falling victim to intense artillery bombardment. Rushing toward the other side was hazardous work.

In wet weather, a mass of mud and large pools of water filled artillery blast sites, making it even more difficult to cross "no-man's land." The trenches were often flooded with water

President Woodrow Wilson asked Congress to declare war against Germany and the Austro-Hungarian Empire on April 2, 1917. The Congress did so on April 6. The US Army, deliberately kept small at about 98,000, now faced an immediate requirement to send an Expeditionary Force to Europe to fight against Germany. All males aged 21 and 30 were required to register for military service.

Linnie Leckrone was born in 1893 in Tonti Township, Marion County, Illinois. I was fortunate to speak to her daughter, Mary Jane Bolles Reed (now deceased). She told me "Linnie" was her mother’s given name. Some sources list her as "Lena" and "Lina." Mary Jane provided me with some good insights.

Linnie attended schools in Salem, Illinois, and then graduated from the Training School for Nurses at Wesley Memorial Hospital in Chicago, part of Northwestern University’s Medical School. Her brothers, Orris, Dwight, and Lyle, also served during the war. This is a photo of her when she was a student nurse. As an aside, Wesley opened in 1888 in Dearborn, Ohio, and moved to Northwestern University-owned land in 1890 and thus became affiliated with its medical school.

While at Wesley, Miss Linnie worked the floors on 12-hour shifts, initially earning about two dollars per month and then raising it to three. She graduated in 1916. Her wages on the floor were undoubtedly low, but working there also helped pay her tuition.

She was very good friends with Irene "Robe" Robar and graduated with her. After graduation, Leckrone and Robar decided to join the war effort and serve in the ANC. Patricia Jernigan, writing for the Summer 2007 edition of The Flagpole, the newsletter of the US Army Women's Foundation, said Leckrone and Robar joined the ANC in May 1917 and were sent to France in January 1918 to serve with Base Hospital No. 66, a hospital to the rear, in Neufchâteau, France.

After reading Linnie's diary of events, her daughter alerted me that the Red Cross called Linnie on June 12, 1917. But Linnie had already joined the Army ANC.

The ANC was established in 1901. When needed in WWI, it was only 17 years old. It was small, with 403 nurses on active duty and 170 in the reserves. However, there were 8,000 nurses in the American Red Cross's nursing service reserves. It took no time for the Army to realize that the American Red Cross was the only means by which it could quickly build a wartime hospitalization system at home and, more importantly, abroad.

By May 1917, the War Department called upon the American Red Cross to mobilize six of its base hospitals for immediate shipment to France to serve with the British Expeditionary Forces and care for their wounded. The next such hospitals to arrive later in the summer of 1917 were assigned to American forces. WWI was a driving force in the rapid development and expansion of the American Red Cross.

The Red Cross Department of Military Relief decided to organize and equip 50 base hospitals, 500 beds each. Experience on the ground once they were deployed to France meant that they would become 1,000-bed hospitals, often rising to 2,500 beds.

The medical teams and base hospitals arrived in Europe before US combat forces. Base Hospital No. 4 was organized at Lakeside Hospital, Cleveland, Ohio. It was the first unit of the Army to reach Europe. On May 25, 1917, it deployed to Rouen, France, about 70 miles northwest of Paris, as part of the overall AEF, even though the AEF combatants had not yet arrived.

General John J. “Blackjack” Pershing, USA, was selected to command the AEF on the Western Front. He arrived in France on June 13, 1917. His first task was to organize his command.

Recall that the US declared war on the German Empire on April 6, 1917, nearly three years after the war started. It’s now June 1917. One of the reasons the troops took that long to get to Europe and took so long to get in the fight was because Pershing insisted they be well trained, and he wanted to build up his forces first. His goal was to be self-sufficient, independent, well-trained, and self-contained. He refused to have his troops used as filler where the French and British were weak and refused to place them under foreign command. Over time, he would have to relax some of these guides.

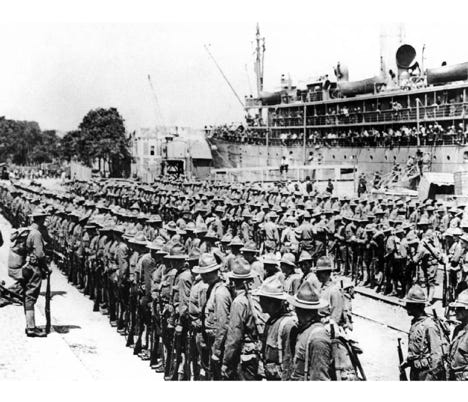

The first American AEF troops, about 14,000 strong, landed at St. Nazaire, France, on June 26, 1917. This photo shows the AEF troops landing at St. Nazaire. The AEF grew to over one million by May 1918. By June 1918 Americans were arriving at the rate of 10,000 per day. The AEF would build to about two million during WWI. The Germans found themselves outnumbered.

On July 25, 1917, Leckrone was notified that she might be called up for duty. Then, on October 31, she was informed that she was going to France. She had been working at Wesley Memorial Hospital in Chicago, but on November 5, she had to leave to pack her bags. She made her way to Union Station in New York on November 8. She and Robar left Union Station on November 9 and hopped a boat to Ellis Island. Linnie noted that they were assigned to a dorm with 24 beds.

Her time at Ellis Island is fascinating. Beginning June 15, 1917, Ellis Island was a nurses' mobilization station.

Ellis Island was originally one island, Island No. 1, shown to the right on the graphic. It was built up, and the buildings received additional floors. This entire area was mainly for receiving and processing immigrants. Using additional landfills, Islands 2 and 3 were built up.

The US Army Department of Medicine has reported that the Bureau of Immigration agreed to allow the Army Medical Department to use certain portions of the island as a nurses’ mobilization center.

Enlisted men on duty at the hospital and 260 patients could use island No. 1, the original island.

Island No. 2 was an administrative area and also had 280 surgical patients. The nurses lived on the third floor.

The officers at the hospital lived in the Island No. 3 buildings.

Note that differentiation was made between officers and nurses. The Army knew it needed thousands of nurses in Europe but did not know how to integrate them into the military rank structure. The general belief was they ought to have officer status, but the Army did not know how to do that and frankly did not have the time, you might even say the desire, to work the problem then. So, the Army, in all its wisdom, decided they would be called “Miss” or “Nurse.” Miss was their rank. Miss Leckrone and Miss Robar received medals for their heroism, and their certificates referred to them as Warrant Officer Three!

As an aside, the Army had similar problems with the doctors, often bestowing Army rank that was technically unofficial.

Not only was rank an issue for the nurses, but so was their clothing. When WWI began, nurses had no uniform. But by 1918, they were starting to fashion one, wearing stripes, service, and gallantry medals on new field uniforms, “badges of honor.” I've seen multiple uniforms: outdoor, indoor ward, operating room, and I suspect others.

The mobilization center for the nurses was a kind of boot camp. They came from the civilian sector and had to be acquainted with Army law and order. The US Army Medical Department has described the nurses’ mobilization center,

"Mobilization as applied to members of the Army Nurse Corps, consisted in assembling the nurse personnel of the units destined for overseas, which were for the most part scattered among several cantonments; equipping these women with uniforms; the preparation of pay accounts, insurance and allotment papers, passports, and identification cards.

“Upon the Office of the Surgeon General devolved the duty of arranging for suitable mobilization stations and of ordering nurses to such stations, but to the chief nurses of these mobilization centers fell the task of the detailed paperwork, keeping track of the large groups of women under their supervision, and the instruction of new chief nurses in regard to Army Regulations, Army customs, and the conduct of all the affairs of these large groups of women who, for the most part, so recently had become a part of the Army Nurse Corps and for whose affairs there naturally existed different business methods.

"Days spent at the mobilization stations were full of interest and intense excitement. Every morning each nurse had to be present at roll call, followed by military drill. After the matter of passports, inoculations, uniform, and equipment had been attended to, there were the rounds of shopping and sightseeing. It should be noted here, however, that nurses were never allowed to stay away from the mobilization station overnight and only for a few hours at a time during the day because it was never known when sailing orders for a unit might arrive."

I believe Leckrone took her oath of allegiance and was sworn into the Army and the ANC while at Wesley. She then went to the Ellis Island Nurses' Mobilization Station for training on "Army life and protocol."

While at the Ellis Island center, she received orders to Hospital No. 66, which was being organized at Camp Merritt, New Jersey, the primary training base for medical personnel. The goal was to train everyone assigned to this hospital at Camp Merritt. While in the US, Hospital No. 66 was much like a package of people who would operate and administer it. They trained together and sailed to France together.

However, Linnie did not go to Camp Merritt. She, Miss Robar, and two other nurses sailed for France on December 11, 1917, aboard Road Mail Ship (RMS) Adriatic, shown here. Linnie and Robar joined Hospital No. 66 near Neufchâteau in northeastern France.

They were housed in the French Rebeval Barracks. Base Hospitals such as this were far behind the lines of combat. Hospital No. 66 was the first base hospital organized from the Regular Army and was designated as a genitourinary hospital, though it never functioned as such. Genitourinary is a word that refers to the urinary and genital organs.

No. 66 took over a 500-bed hospital at the Rebeval Barracks from two hospitals of the 26th Division. It arrived in France on January 13, 1918, and became operational with 500 beds on January 19. Shortly after arriving, its capacity increased to 2,600 beds.

The Rebeval Barracks were typical old French kasernes, unsuitable for hospitalization. The Germans constructed them during their occupation of France following the Franco-Prussian War. They were made from stone, brick, and cement and had stone floors. They had been used as a veterinary hospital for horses since early 1917. When the Base Hospital No. 66 staff arrived, Leckrone and Robar shared the same enclosure.

Base Hospitals were far to the rear, and wounded soldiers, making it this far, had a reasonable chance of survival. They were usually located near the army’s principal bases and would have a rather large staff. For example, one had 32 Medical Officers, three Chaplains, seventy-three female Nurses, and 206 troops acting as orderlies.

The military concept was for the nurses to work in the rear, but that did not last long. Small specialty teams were organized to get closer to the troops, and the female nurses went in close to the battle. This was especially true to care for those wounded by gas and shock from explosives. Hemorrhagic shock from explosives was a considerable threat.

My impression of Miss Leckrone and Miss Robar is that they were real tigers. They did not want to remain at a base hospital in the rear. They wanted to be near the action and care for the wounded immediately after being struck or injured.

Patricia Jernigan wrote for the Summer 2007 edition of The Flagpole, the US Army Women's Foundation newsletter. She wrote,

“In July (1918), an urgent call was received for two nurses to serve on a shock team with Field Hospital No. 127 supporting the 32d Infantry Division at Château-Thierry. Nurses Leckrone and Irene Robar, both good friends, volunteered for this dangerous duty. With thousands of casualties per day streaming through the hospital, the work was extremely intense, and conditions were difficult. The hospital was close to the front, and the staff often worked on the wounded under incoming artillery fire.”

Joshua S. Goldstein, writing War and Gender: How gender shapes the war system and vice versa, wrote,

"Army efforts to keep women to the rear proved difficult. 'Women kept ignoring orders to leave the troops they were looking after, and bobbing up again after they had been sent to the rear.' Some of the US women became 'horrifyingly bloodthirsty' in response to atrocity stories and exposure to the effects of combat."

Leckrone and Robar were now assigned to a shock team at a field hospital. Leckrone said the place was almost destroyed. The walls were shattered. Both nurses were the first women at No. 127. Leckrone described conditions as "primitive," filled with hardships.

Leckrone's daughter told me Linnie said it was always raining at Nr. 127. One time, when she walked at night from the hospital area to her tent, she fell into a water-filled shell hole. She said she was so tired that she just sat there and cried and then pressed on. This was nothing like Hospital No. 66, where lights were kept on all night instead of using candlelight, and they got to enjoy ice cream three times a day.

Let’s first address the field hospital and then the shock team.

Military Medicine publication 173, 5:493 of 2008 said this about field hospitals:

“In the schema of medical care during World War I, field hospitals were intended to be closest to the front line. Although nurses were initially not assigned duty in a field hospital, an unknown number of them were temporarily attached as members of specialty teams that augmented hospitals in times of need. The categories of common specialty teams included shock, splint or orthopedic, and surgical or operating teams.”

Field Hospitals in WWI usually followed advancing and retreating troops in combat. They were placed close to the action, and when combat was heavy, they moved frequently. Volunteer ambulances transported the wounded from the front to the field hospital.

Nurse Ellen N. La Motte, one of the first American nurses to serve in France at a field hospital, wrote,

“It is pretty much always like this in a field hospital. Just ambulances rolling in, and dirty, dying men, and the guns off there in the distance! Very monotonous, and the same, day after day, till one gets so tired and bored. Big things may be going on over there, on the other side of the captive balloons that we can see from a distance, but we are always here, on this side of them, and here, on this side of them, it is always the same. The weariness of it—the sameness of it! The same ambulances, and dirty men, and groans, or silence. The same hot operating rooms and beds, always full, in the wards. This is war. But it goes on and on, over and over, day after day, till it seems like life.”

In their paper, “The Overlooked Heroines: three Silver Star Nurses of World War I,” Lt. Colonel Richard M. Prior and William Sanders Marble provide some insights into Field Hospital 127,

"Little is known about the activities of Field 127 Hospital on July 29, 1918, in support of the Aisne-Marne Offensive or the exact circumstances under which Leckrone and Robar would be awarded the Citation Star. From June 25 to July 20, Field 127 was executing its mission at Massevaux, Alsace. With the crisis in front of Paris, the division was moved to the Marne sector and Field 127 moved 450 kilometers to the Ecole Jean Mace at Chateau-Thierry where they operated a 500-bed hospital for the seriously wounded from July 28 to August 3. The hospital occupied the second floor of the large, old school located 22 kilometers behind the front line of the 32nd Division, close enough for regular shellfire and occasional bombing raids since the city was a communications hub (the first floor was occupied by Field 166 of the 42nd Division.) During the same period, Field 127 received 113 wounded patients and operated on 21 of them."

In the “Report of the Surgeon-General, United States Army to the Secretary of War, Vil. II, 1919," the authors commented on Field Hospital 127:

"On July 28, Field Hospitals No. 126 and 127 were established at Ecole Jean Mace at Château-Thierry, one for gas and one for non-transportable wounded."

Later in this report, the Surgeon-General said Field Hospital No. 127 was mainly used for triage and advanced surgery. This is most interesting. Miss Leckrone's daughter, Mary Jane, told me that Miss Leckrone arrived at Ecole Jean Mace at Château-Thierry on July 28, 1918, which is the exact day it was set up, and the day before it was hit with artillery. Linnie and Miss Robar worked with their patients despite the artillery shells booming in.

Let’s switch to the shock team part of Field Hospital 127. Shock Team No. 134, consisting of two nurses and two corpsmen, was attached to Field Hospital No. 127. Leckrone and Robar were the two nurses.

Leckrone would write,

“I felt lucky to have been picked. Our work was with shock cases, the ones who lost so much blood. We lost more than half of them.”

Much of the time, Leckrone's first action was to treat hypotension or low blood pressure. In the case of WWI, it was the result of excessive bleeding, primarily from Hemorrhagic shock from explosives and massive wounds from machine-gun fire.

She told her daughter on one occasion about holding a young, badly wounded soldier in her arms,

“He was just a boy, no more than 16 years old. He called me 'Mom.' He died the next morning.”

Once again, borrowing from Lt. Col. Prior and William Marble,

“The primary function of shock teams was the resuscitation of wounded soldiers who were hypotensive secondary to blood loss, usually as a result of a femur fracture or multiple trauma, and therefore too ill to survive immediate surgery. Those soldiers suffering from significant hypotension were placed in a segregated area known as the shock ward. Typically, a patient with a blood pressure below 100 systolic was triaged to the shock ward where a team of specially trained physicians, nurses, and enlisted men attempted to stabilize them. The therapies used were primarily warming and intravenous fluids, which included either citrated blood or use of 'gum' solution, a plasma expander. Their efforts predated the type and cross-match of blood products. Occasionally, a patient who deteriorated while undergoing surgery had to be removed from the operating room and transferred to the shock ward to be stabilized before the surgery could resume.”

John Campell, writing “WWI: Medicine on the battlefield,” wrote there were four kinds of cases that had to be sorted out: gas injuries, shell shock, diseases, and wounds. He wrote,

“World War I was the first conflict to see the use of deadly gases as a weapon. Gas burned skin and irritated noses, throats, and lungs. It could cause death or paralysis within minutes, killing by asphyxiation."

Marek Pruszewicz wrote,

"Mustard gas, could kill by blistering the lungs and throat if inhaled in large quantities. Its effect on masked soldiers, however, was to produce terrible blisters all over the body as it soaked into their woollen uniforms. Contaminated uniforms had to be stripped off as fast as possible and washed - not exactly easy for men under attack on the front line."

John Campbell commented,

“Some injuries were not physical. Most soldiers got used to living in muddy areas filled with rats, rotting corpses, and exploding shells, but others could not. As the war progressed, a mental illness caused by these conditions became known as shell shock. Sufferers could be hysterical, disoriented, paralyzed, and unable to obey orders.

“Soldiers lived and fought in trenches that were little more than swamp-like holes in the ground—a perfect breeding ground for disease. Doctors and nurses could do little to help soldiers with influenza and intestinal flu, and these diseases killed more men than machine gun bullets.”

One of the dominant maladies the shock teams had to deal with was Hemorrhagic shock from explosives.

Hemorrhagic shock is a life-threatening condition that results when one loses more than 20 percent (one-fifth) of his body's blood or fluid supply. This severe fluid loss makes it impossible for the heart to pump sufficient blood to the body. Speaking in general, explosions, especially high-energy explosions, are a primary cause of hemorrhagic shock because of the impact of over-pressurization waves hitting the body’s surfaces.

In WWI, artillery bombardments were the most common cause of high-energy explosions. Soldiers first feel the concussive force of the explosion, often referred to as overpressure. They feel like the air is sucked out of them. Very shortly after the overpressure strikes and radiates outward, shock waves create a vacuum; oxygen is pushed out, sucked back in, and immediately pushed out again. Among other things, blood is forced out of organs and arteries upwards toward the brain, hemorrhaging. The nurses, of course, had to be “Jacks of all trades.” I have read that one of those trades for Leckrone at the front was triage.

During WWI, triage meant medical people rated patients with a color code. A red tag meant Priority 1. The patient’s life is in immediate danger and requires immediate medical treatment. The yellow tag was used for patients whose lives were not in immediate danger. These require urgent care but not immediate care. The green tag meant the patient had minor injuries and would eventually need treatment. And finally, the black tag. The patient was either dead or had such extensive injuries that they could not be saved with the limited resources available.

The History of American Red Cross Nursing addressed the experience of nurses at Château-Thierry, which is where Miss Leckrone served,

"American troops went into action at Château-Thierry and the wards of all American sanitary formations were crowded with wounded men. Nurses, surgeons and orderlies … worked until they could work no more. Discouraged by apparently futile efforts to improve conditions, exhausted by the herculean labor demanded of them, in many cases harried by constant bombardments and bewildered by the sight and suffering of the disfigured men, the nurses were sobered and numbed by fatigue and horror into silence and disillusionment. War no longer appeared to be a fine, a brave, a heroic thing."

I canvassed for a few stories from or about WWI nurses to underscore what they experienced.

"Imagine a ward full of men with their brains oozing out of bad head wounds … They come in lying on stretchers in pools of blood all soaked through to the skin... also plastered head to foot in mud … The mortuary was full up, the dead Tommies had been piled up there each in a blanket with their bare feet sticking out.” Nurse Violet Gossett, Britain

“Amputations are being done almost every day. Yesterday I went down to the Theater Hut to see how our nurses were going to handle a very bad case...Our people at home would marvel to see what fine work can be done when all the water used has to be heated on top of a small oil stove and all the instruments boiled the same way … "...what with the steam, the ether, and the filthy clothes of the men...the odor in the operating room was so terrible that it was all any of them could do to keep from being sick...no mere handling of instruments and sponges, but sewing and tying up and putting in drains while the doctor takes the next piece of shell out of another place. Then after fourteen hours of this with freezing feet, to a meal of tea and bread and jam, then off to rest if you can, in a wet bell tent in a damp bed without sheets, after a wash with a cupful of water...one need never tell me that I women can't do as much, stand as much, and be as brave as men." Miss Julia Stimson, USA

"Convoy arrived, about 400 – no equipment whatever – just laid the men on the ground and gave them a drink. Very many badly shattered ... All we can do is feed them and dress their wounds. The heat and the flies are terrible here (Greece)." Matron Grace Wilson, Australia

"After arriving on the Western Front (Miss Helen) Fairchild was sent to Casualty Clearing Station No. 4 at Passchendaele on 22nd July, 1917. Exposed to mustard gas during November 1917, Fairchild began suffering from severe abdominal pains. Fairchild continued to work and it was not until just before Christmas that a Barium meal X-Ray revealed that a large gastric ulcer was obstructing her pylorus. Doctors suggested that this had probably been worse by the poisonous gases used against the Allies. Fairchild underwent a gastro-enterostomy operation on 13th January 1918. Initially Helen Fairchild did well but on the third day she began to deteriorate and after going into a coma she died on 18th January 1918." Spartacus International

"I am sure you will understand why when I tell you that we are surrounded by sadness and sorrow all the time ... do you know, Muriel, that as many as 72 operations have been performed in one day in our hospital alone ... you could not imagine how dirty the poor beggars are, never able to get a wash, mud and dirt ground in and nearly all of them alive with vermin. They feel ashamed being so dirty, we always tell them that if they came down any cleaner we would not think they had been in it at all." Matron Gertrude Doherty, Australia

"(It's) July 17, four hundred eleven patients arrived, many gassed with phosgene, mustard and chlorine gas. Many acute surgical cases that had to be operated on. These patients came directly from the Chateau Thierry Front & were among the early casualties of the 2nd Battle of Chateau Thierry. The mustard gas causes horrible body burns. A patient was brought in one day wrapped in a blanket, no clothing his body burned black & literally raw, face black, eyes completely swollen shut & he was suffering agonies. This was a case of mustard gas burns. Another patient, gasping & coughing, blue in the face, intense pain in his chest on every respiration. This, of course was a case of phosgene gas poisoning. The wounds are caused mostly by high explosives, machine gun bullets & shrapnel. A Kansas farmer boy was brought in half of his abdomen was shot away & intestines protruding. Bishop Israel gave him the last sacrificial rites before he was rushed to the Operating Room. He had been driving a soup kitchen, next thing he know both horses had been shot away, while he was still sitting with the reins in his hand then he discovered he had been wounded.

“All day long from morning until night I went from bed side to bed side doing dressings. I had an orderly to assist me. ….strenuous days. These patients were rushed directly from the front. I always dreaded removing bandages for fear of hemorrhage. I never knew what I was going to find, there were many missing limbs, horrible deep wounds.” Emma Elizabeth Weaver, USA

“And then there is Hilley. His hip was shattered by an explosive bullet when he was crossing a river, and he would have drowned if his chum hadn’t come back to him and carried him out on his back. There is more to it, but I’m not sure I’ve ever got it straight. Anyway, Hilley’s chum got the Victoria Cross for it. But Hilley, as he says, got nothing but a bum leg. He is an Irish Guardsman, and everyone in the hospital knows him. Long and thin, with a fine, keenly intelligent face which is proudly decorated with a neat black mustache, he has lain for nine months tied to a Balkan frame, and he is the heart and soul of A 1. He bucks the boys up no end. Always singing, or joking, or wrangling about something. He never complains, though he is tortured daily. We have always been great friends. We have old jokes that we cherish, and certain formulas of greeting and leave-taking. Hilley, long ago, started the boys saying “good night” to me, all in one voice. They think it is a great joke, but it’s a lot more than that to me.” Helen Dore Boylston, USA

Miss Leckrone and Miss Robar came home after the war. Linnie worked one year as a school and county nurse in Colorado, met her husband, Ralph B. Bolles, and married him in 1922 at age 29. They settled on a farm and raised a family of four, two boys and two girls. While retiring officially from nursing, she continued nursing in her community. She would walk to farms and visit patients. There were always accidents and illnesses in the community for her to tend to. That was in addition to working on the farm and raising four children. Furthermore, her in-laws moved in with children, and she cared for them as well.

Her daughter described her as conscientious, calm, patient, skillful, and creative. She cooked what the farm produced, including rabbits caught or shot. Mary Jane said her mother was an industrious, hard worker. She would wash the clothes and hang them outside to dry, scrub the windows and walls, and tell her children to go outside and play—"I'll take care of this." She was also resourceful, repairing hand-me-down clothes for the children and making dresses for the girls.

In addition, Linnie Bolles managed a cucumber and pickle receiving station on the farm every summer. Mary Jane commented that Linnie knew how to charm the farmers, who would get irate over the money they were paid for the loads of cucumbers. She was assertive, tough, and persuasive — one guy said she was the "boss." Mary Jane said Linnie rarely complained and failed to realize when perhaps she was being manipulated. She enjoyed having fun, played a lot of canasta, and was a gracious and hospitable hostess and entertainer, a cheerful woman.

At the end of the day, Linnie Leckrone Bolles was a nurse all her life, courageous and unflappable.

On the light side, Mary Jane asked her mother if she had met any men in France and if she had dated. Linnie replied, "I had no time to flirt!"

Linnie died in 1989 and was buried at the Hillcrest Cemetery in Rocky Ford, Colorado.

Three Army nurses received the Distinguished Service Cross (DSC), the second-highest military award for a member of the United States Army. All three continued working under heavy German shelling and bombing.

Miss Beatrice MacDonald (McDonald) (left) was hit by shrapnel and lost an eye.

Miss Isabelle Stambaugh (center) was working with a surgical team and was wounded by shell fire from an air raid.

Miss Helen Grace McClelland (right), a tent mate of Beatrice MacDonald, continued work and further tended to stop the hemorrhage from MacDonald’s wounds. Also, Miss MacDonald received the Royal Red Cross First Class from Britain.

During WWI, commanders down to the company level could cite individuals for “Gallantry in Action.” A general officer would have to sign a citation published in orders authorizing an individual to wear the 3/16 in. silver Citation Star on their Victory Ribbon, shown here.

Miss Linnie Leckrone received this award. The official date of award is November 27, 1919, a year after the war had ended and Leckrone had returned to the US,

"Miss Linnie E. Leckrone, Army Nurse Corps, for distinguished and exceptional gallantry at Château-Thierry on 29 July 1918 in operations of the American Expeditionary Forces in testimony thereof, and as an expression of appreciation of her valor, I award her this Citation.

"Awarded on 27 November 1919, John J. Pershing, Commander-In-Chief."

The Silver Star, shown to the right, replaced this citation in 1932. It is the military's third-highest decoration for valor in combat.

Leckrone and others received their Silver Stars years after the end of WWI. Those individuals who had received the Citation Star had to contact the War Department to request the Silver Star medal.

Miss Leckrone never knew she had received it. In a footnote to First World War Nursing: New Perspectives, Alison S. Fell and Christine E. Hallet said it was also likely she did not know she received the Citation Star since it was not affixed to her Victory Medal.

On July 31, 2007, Major General Gale S. Pollock (left), acting Army surgeon general and chief of the Army Nurse Corps, presented the Silver Star (posthumous) in lieu of the Citation Star to Mary Jane Bolles Reed (right), Leckrone’s daughter.

Click to zoom graphic-photo