DUTY, HONOR, COURAGE, RESILIANCE

Talking Proud: Service & Sacrifice

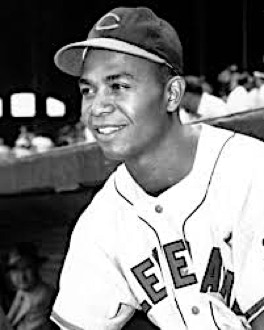

Larry Doby, Nr. 14: Quiet “courage, dignity”

This story is about Larry Doby, a Major League Baseball (MLB) player. You might wonder why I am including it in “Talking Proud.” Larry Doby was, as one person said, “a role model for the ages.” Some people reading this might not know Doby’s place in American history. That’s why!

Have you heard of Hinchliffe Stadium in Paterson, New Jersey? It holds a crowd of about 7,500. It was built in 1932 and was closed in 1996. It fell into disrepair but was reborn. It reopened in 2023 and is home to the New Jersey Jackals professional baseball team. And, sports fans, Larry Doby played center field here in the 1940s for the Newark Eagles of the Negro National League. The New York Black Yankees and the Black Cubans also played here.

You might ask, “So what?”

Bill Veeck, the owner of the Cleveland Indians American League baseball team, told Doby this when he signed his first Major League Baseball contract with the Indians in 1947,

“Lawrence, you are going to be part of history.”

And that’s what Larry Doby was: a part of American history.

Before going to the Indians, Doby played second base for the Newark Eagles. One writer said,

"When Doby was in your infield, the only thing that got through was the wind."

Doby was hired as a second baseman for the Indians, but he had to switch to center field because the Indians were well-equipped in the infield. Tris Speaker, a former Indians Hall of Fame center fielder, trained Doby to make the switch. Speaker was briefly a former Ku Klux Klan member, as were many Americans, but he willingly chose to train Doby and clearly did it well.

While with the Cleveland Indians in the Majors, he batted .283 with 253 home runs and 969 runs batted in (RBI) over 13 years. He hit at least 20 home runs in eight consecutive seasons, leading the league in 1952 and 1954. He won the home run title one year and the RBI title once. He played in six consecutive All-Star games, and his team won two league pennants and a World Series, finishing second behind the famous New York Yankees four times.

The Indians retired his number 14 in 1994. The US Senate passed legislation to honor Doby posthumously with the Congressional Gold Medal in December 2023. Speaker of the House Mike Johnson said,

"Up until Larry took the field for the Indians in 1947, the existence of Black athletes in sports was regarded as an experiment. His ascent to the major leagues was an affirmation that not only do they belong, they make the game much better."

He has been elected to the Cleveland Indians Hall of Fame, the Major League Baseball Hall of Fame, the South Carolina Athletic Hall of Fame, and the New Jersey Hall of Fame. New Jersey Governor Phil Murphy signed a joint resolution declaring that Larry Doby Day will be on July 5 each year. July 5, 1947 was Doby first at-bat for the Indians, against the Chicago White Sox.

Governor Murphy pointed out that baseball was central to American culture and history, and Doby greatly impacted the state’s history. New Jersey Senator Ruiz said,

“(Doby) rose out of the working classes of Paterson to become an American icon and role model.”

The present-day Cleveland Guardians also proclaimed July 5 “Doby Day.” Camden, South Carolina, honored him with four signs along highway U.S. 521 about 300 yards south of I-20. The first sign declares,

"Camden Birthplace of Baseball Hall of Famer Larry Doby."

Doby once remarked,

“Growing up in Camden, we didn't have baseball bats. We'd use a tree here, a tin can there, for bases.”

Larry’s father, David, died when Larry was eight. His mother and Larry left their home in Camden and moved to Paterson, New Jersey, four years after David drowned. Though born in South Carolina, Paterson has claimed Doby as theirs.

In Paterson Eastside High School, Doby was an all-state athlete, earning 11 letters in four sports: football, basketball, baseball, and track. He won a basketball scholarship at Long Island University but switched to Virginia Union College because he intended to become an officer, and it had ROTC. But Uncle Sam grabbed him first, and off to the Navy he went.

John McMurray wrote about his journey into the Navy,

“At the time, Doby had concern about being drafted into the military during World War II. He made the difficult decision to transfer from Long Island University to Virginia Union College, where he would play basketball for coach Henry Hucles. Doby believed he could transfer into an ROTC program there. Yet he was drafted into the Navy at the conclusion of the basketball season.

“The mandated racial segregation of the military at the time left a deep impression on him. He was assigned to Camp Robert Smalls, the Black division of the Great Lakes Naval Training Station, outside Chicago.

“Due in large part to his outstanding physical condition, Doby was able to become a physical education instructor there. He kept his baseball and basketball skills sharp by playing in the afternoons.”

He was honorably discharged in 1946.

Doby used his time in the Navy to his advantage. He played baseball and basketball when he could and got to know future NFL Hall of Famer Marion Motley. He began what became a lifelong friendship with Washington Senators star Mickey Vernon. Vernon wrote to Senators owner Clark Griffith, touting Doby’s playing abilities. Doby recalled,

“(Vernon) sent me a gift of some bats when I started the 1946 season with the (Newark) Eagles. It was a gift I’ll never forget.”

As an aside, Billy Goodman was also on the island of Uithi. He, Vernon, and Doby would throw batting practice together.

Playing second base for the Newark Eagles, he teamed with Monte Irvin to form one of the most talented double-play combinations in Negro League history. He batted .354 in 1946, his final season, and led the Eagles to the league championship. That made him the first player to go directly from the Negro Leagues straight to the majors, which he did in 1947.

If the Navy left a deep impression, so did Cleveland and the Cleveland Indians. Jerry Izenberg has written the book Larry Doby in Black and White: The Story of a Baseball Pioneer. Izenberg knew Doby for over 30 years and once commented,

“Cleveland was a segregated town — segregated schools, segregated hospitals, and an amusement park that you didn’t dare set foot in if you were Black. And he was the only Black player in the league in 1947, and oh what he went through…”

Doby told Izenberg about his introduction to the Indians,

“I stuck out my hand. Very few hands came back in return. Most of the ones that did were cold-fish handshakes, along with a look that said, ‘You don’t belong here.’”

Izenberg, writing for The Star-Ledger of Newark, New Jersey, quoted Doby once telling him,

"Now, I couldn't believe how this (cold treatment from the Indians team during his first year) was. I put on my uniform and I went out on the field to warm up, but nobody wanted to warm up with me. I had never been so alone in my life. I stood there alone in front of the dugout for five minutes. Then Joe Gordon, the second baseman, who would become my friend, came up to me and asked, 'Hey, rookie, you gonna just stand there or do you want to throw a little?' I will never forget that man."

His manager, Lou Boudreau, was unenthusiastic about Bill Veeck signing Doby. It was a challenging move for Doby, going directly to the Indians from the Newark Eagles. Everything about the Indians and Major League Baseball (MLB) came to him as a surprise.

Boudreau once told Doby to play first base, knowing he didn’t have a glove. The starting first baseman refused to loan him his glove. It took a secretary to find a first-base glove in the dugout and run it out to him for him to play the position.

A few weeks later, Boudreau sent him in to pinch hit for a batter with no balls and two strikes against him, just one shy of being struck out. Doby was also barred from the front entrances to stadiums in St. Louis and Washington, booed and cursed, and hit by thrown beer bottles and spit, and most of his team and management did not stand up for him or protect him.

In his early days with the Indians, Doby had to eat in separate restaurants and sleep in separate hotels from his teammates.

Otis Livingston wrote about Larry Doby Jr. talking about his dad’s loneliness,

“So the stuff that he had to deal with, even though that was the law of the land, it's just something I can't imagine. He couldn't even stay at the same hotels with his teammates. I remember him saying that that was the loneliest part. When they were playing the game, everybody was together, and they had a common goal and they were all trying to win a game and, you know, it felt like he was part of the team. And then after the shower, you got to go back to a hotel where there's no teammates, you got to go eat where there's no teammates. So those were the lonely times. But I can't imagine it and I'm just glad that it's not like that anymore.”

While at bat, I have read that Doby felt the sting of the loneliness. As a result, he decided to whack that baseball with extra might. Boudreau later commented,

“Larry proved to them (the other players) that he was a major leaguer in handling himself in more ways than one – on the field and off the field.”

This is where we come to Larry Doby, the man. This is why I write about him here on “Talking Proud.”

Doby’s grandmother, Augusta Moore, made him go to church growing up. John McMurray recounts Doby saying,

“I liked what I heard in the Twenty-Third Psalm and the Ten Commandments. Somehow, I got the feeling that the church helped Black people to be themselves. I liked that feeling.”

Doby, by all accounts, was a determined man. He persevered, broke down barriers, was a pioneer, and was consistent. Mel Harder, a Doby teammate, recalled,

“It may have (bothered Doby), but he never complained to the players; when he joined, naturally it was a tough time. But after he was with us a while, he got along pretty good.”

McMurray wrote,

“Doby was more introspective than demonstrative, and his personality could confuse his teammates.”

His son has said of his dad,

"His fire burned within. He was the quiet guy who tried to lead by example, and that's what he did.”

The website JockBio.com quoted Doby,

“(His teammates) got a true picture of me—not a picture of what someone told them. I think that's one of the biggest things that happened in baseball, that we were able to integrate and judge for ourselves what kind of character these people had. You wish that the entire world would be involved in athletics because then you would know what it is to have communication and association.”

Larry Doby publicly demonstrated what a professional he was. He told a college audience:

"I hope that this city and cities across the country will continue to work together to make this a better place for all of us. I think the most important thing, besides being involved in your games, is teaching. Teach your friends, teach your fellow man what it is to love one another."

In 1997, he opened the sixth Larry Doby All-Star Playground, this one in Cleveland's King-Kennedy neighborhood, part of a community rebirth campaign. It was built in 1997 and, with MLB's help, was rejuvenated and opened in 2019. It is now part of the King Kennedy Boys and Girls Club of Cleveland.

This opening of the playground in 1997 was an important event. Bud Selig, the acting commissioner of Major League Baseball, American League President Gene Budig, and Cleveland Mayor White were all there. Cleveland's All-Star catcher, Sandy Alomar, took the first pitch from Doby to get the ceremonies going. Also, a youngster named Darnell Crutchfield from the neighborhood sang the national anthem. Doby made sure to get over to the lad to shake his hand.

Doby felt baseball was an integral part of American culture and American history. He told a college audience:

"I hope that this city and cities across the country will continue to work together to make this a better place for all of us. I think the most important thing, besides being involved in your games, is teaching. Teach your friends, teach your fellow man what it is to love one another."

In his Hall of Fame speech, Doby said,

“You know, it’s a very tough thing to look back about things that were probably negative. You put those things on the back burner. You are proud and happy that you’ve been a part of integrating baseball to show people that we can live together, we can work together and we can be successful together.”

Bob Kendrick, the President of the Negro Leagues Baseball Museum (NLBM) in Kansas City, Missouri, commented,

“Larry Doby was highly educated, he was a true gentleman, and he was a great athlete.”

Bob DiBiasio of the Cleveland Guardians (Indians) has said Larry Doby was one of those,

“Men who through their actions changed the course of baseball. Changed the course of society. And inspired millions.”

Paul Hoynes, writing for The Cleveland Plain Dealer, quoted Detroit’s owner Larry Dolan, who grew up in Cleveland, saying this:

“Larry (broke the color barrier) silently and with dignity. I only met him a couple of times, but even in his mid-70s, he had a graciousness about him."

Joe Morgan knew Doby well, and remarked,

“(He) never focused on the negative. Doby preferred to talk about the positive.”

Todd Dewey has written that Doby often said this to his kids,

“We are stronger together, as a team, as a nation, as a world.”

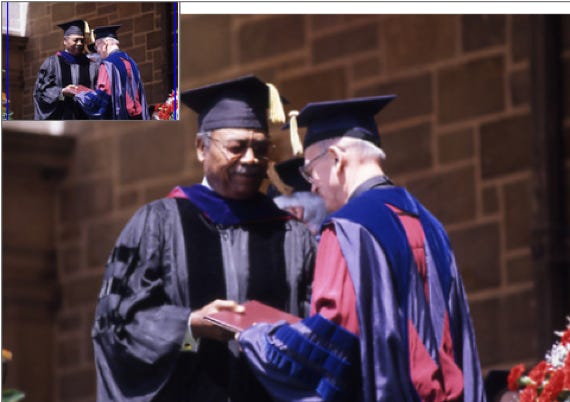

Doby received a Doctorate of Humane Letters from Montclair State College in Montclair, New Jersey, and, according to Dr. Greg Bradsher, he also received honorary doctorate degrees from Long Island University, Princeton University, and Fairfield University.

These traits and achievements are the centerpiece of Larry Doby’s leadership qualities. John P. Kotter, a Professor of Leadership Emeritus at Harvard, has written,

“Leadership is, most fundamentally, about changes. What leaders do is create the systems and organizations that managers need, and, eventually, elevate them up to a whole new level or . . . change in some basic ways to take advantage of new opportunities.”

In short, leadership is a process, a social process. Professionalism is a social quality. Larry Doby had it. He pushed this process along.

One final baseball note, a story that is still being told.

It’s 1948, and the Indians are in the World Series against the Boston Braves, ahead two games to one, best four out of seven. Steve Gromek was pitching for the Indians in game four. The Indians were up against the formidable Boston Braves ace Johnny Sain. The Indians jumped off to a 1-0 lead in the first inning. Doby was in his second season with the Indians. In the third inning, Doby lashed a 410-foot homer to make it 2-0. The Braves scored in the seventh, but the Indians held on to win 2-1. Doby’s third-inning homer won the game. It remains one of Cleveland’s most famous home runs. That home run was decisive and put the Indians in a 3-1 series lead. They ultimately won the series 4-2, their first World Series win since 1920.

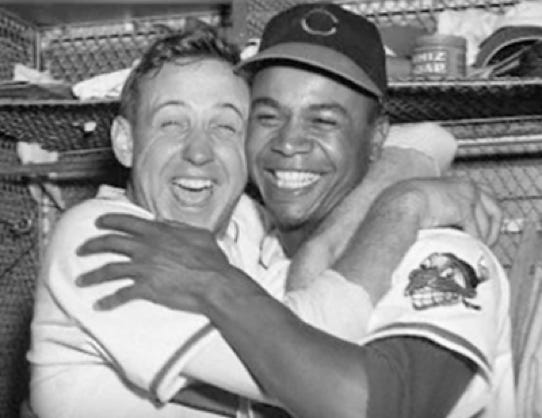

That was the World Series baseball story. The cultural story came after the game.

A news photographer snapped a photo of Gromek after he leaped into Doby’s arms and publicly hugged Doby. It made all the front pages. Jerry Izenberg quoted Doby commenting about that event the day before being inducted into the Hall of Fame:

“It was the first picture of a black and white man embracing at home plate. America needed that picture and I will always be proud that I could help give it to them.”

It should have come as no surprise to anyone that Steve Gromek would publicly embrace Larry Doby for the world to see. Those who knew him saw him as a kind and loving man, intelligent and talented, who never asked more of others than he expected of himself, and who knew no limit when it came to helping family or friends. Younger players would ultimately call him "Pappy," a name that stuck with him until he died in March 2002 at 82.

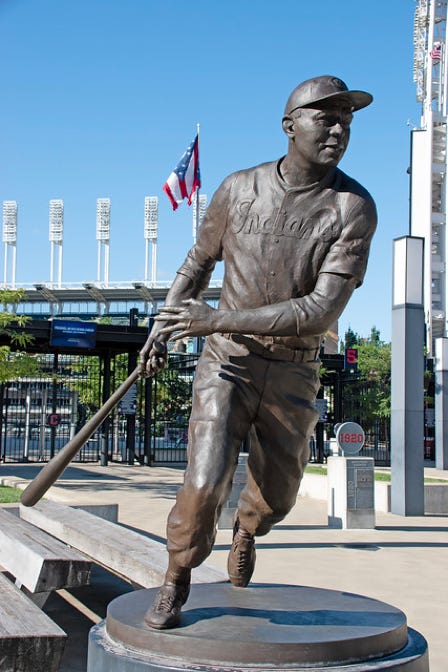

A statue of Larry Doby was added outside the gates of Cleveland’s downtown Progressive Field in 2002. David Deming created the statue. It has been described this way,

“Doby's statue is outside the gates at Progressive Field. His bronze likeness has been captured in the middle of the most exhilarating moment in baseball: right after a home run. Doby's front foot is planted and prepared to launch him around the bases. His eyes are fixed on an imaginary first base, determined and focused. His hands, swung out to his right, are throwing the bat behind him. Doby is leaning forward, full tilt, and his feet are on the furthest edges of the base, ready to spring off at a moment's notice. Though he may be a statue, some people still feel like they're in danger of being knocked over when they're in his path.

“But the trails that Doby blazed weren't always just around the bases, in the record books, or on the stat sheets. Doby blazed the trail for integration on every front when he became the first (Black player) in the American League. In 1948, Doby became the first Black player to ever hit a home run in the World Series.

“It is hard enough to make it to the MLB as is, but to make it and thrive like Doby did in the face of so much resentment, so many obstacles, and such great odds, is truly a feat that no monument could ever conceivably do justice, but Deming's magnificent tribute to one of the most historic players of all time certainly comes close.”

Larry Doby’s outlook was like this,

“I look back and see how far this country has come because of the integration of baseball. I think that if the country itself had progressed as much as baseball has progressed, we wouldn't have a lot of the problems we have.”

Larry Doby’s leadership was a process. He pushed this process along.

Click to zoom graphic-photo