DUTY, HONOR, COURAGE, RESILIANCE

Talking Proud: Service & Sacrifice

“Nobody kicks ass without a tanker’s gas - nobody!”

Some years ago, I received an email from Lori T. Davis, whose maiden name was Elwood, “Wood” for short, and who is shown here in an old photo. She was an Inflight Refueling Specialist on the USAF's KC-135 tanker. She was among the first women to get such a job. She remarked that she had plenty of war stories.

Airman First Class (A1C) Lori Wood Davis was a boom operator, a “boomer” for short. She had two stripes, the third lowest enlisted rank, but she was in charge when it came time to refuel another aircraft while in the air.

Lori conveyed some good ol’ USAF refueling jargon, which I’ll pass on,

“Let’s face it… I laid on my belly and passed gas… I stuck the pole in the hole… I was chauffeured to work and back by officers...When I did get out (of the USAF), I married a Boom Operator. Our kids are ‘Baby Boomers.’ Ha!”

The KC-135 is now almost 70 years old. The first production Boeing KC-135A Stratotanker, 55-3118, was named City of Renton and made its first flight on August 31, 1956. There she is to the right, taking off on her maiden flight. The first KC-135A was delivered to Castle AFB, California, in June 1957; the last was delivered in 1965. She has grown up to become the KC-135T, far different from the City of Renton.

The USAF has found replacing it to be a tough nut to crack. In 1981, it tried the KC-10, a variation of the DC-10 airliner known as the Extender. However, it was not the “futuristic tanker” the USAF wanted and was also costly to operate. The KC-10 flew its last mission in late 2023 and was retired.

In 2011, the USAF selected Boeing Co. to deliver the KC-46 Pegasus, a Boeing 767 civilian airliner variation. It plans to buy 179, of which 84 have been delivered. But the aircraft has issues.

The USAF is looking for a tanker “small, stealthy, and capable of accompanying combat aircraft into contested airspace.” This is a complex requirement, given the large amount of aviation fuel it must carry. To my knowledge, such an aircraft has not yet appeared.

However, I will mention that work is being done to employ unmanned aerial refueling aircraft. The USN has done a lot of work on this with the MQ-25 Stingray. It employs only the drogue and probe system which I will address later.

Then US Secretary of the USAF Heather Wilson said this in 2018,

“Aerial refueling will be the biggest shortfall in our Mobility Force.”

These are thorny issues, far above my paid grade.

So, let’s return to the trusty old KC-135. Like the B-52, it will probably have to live another decade, maybe more.

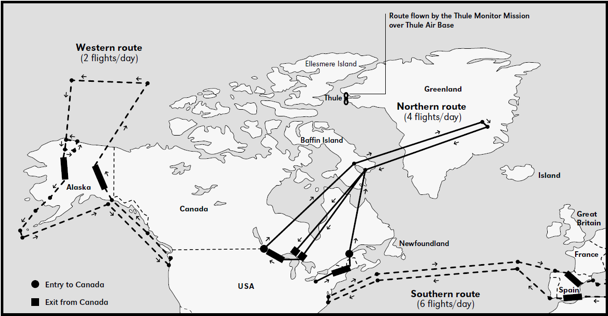

I had my first and only ride in a KC-135 back in 1966. I was an Air Force Reserve Officer Training Cadet (AFROTC). I flew aboard a KC-35 tanker out of Plattsburgh AFB, New York, to broaden my horizons. The mission was to refuel a B-52 over “someplace” at night. I assumed the B-52 was one of those on an “Operation Chrome Dome” mission loaded with nuclear bombs meant for the USSR if required. Back then, B-52s maintained continuous airborne alerts and were ready to attack targets in the Soviet Union. This map provides an overview of those US airborne alert routes. I suspect we refueled the B-52 over Greenland or the Atlantic Ocean.

After arriving at Plattsburgh, the cadets joined their KC-135 crew. The chief NCO on my flight went through emergency procedures, which I paid close attention to as I had flown commercially only once or twice.

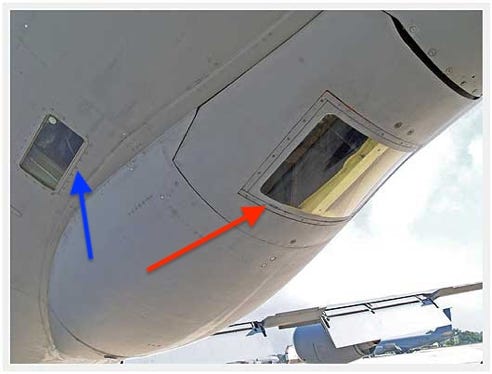

Our bail-out procedure was to exit the aircraft using the aft escape hatch shown by the red arrow on this Plattsburgh-based KC-135.

The NCO showed us how to roll out of the escape exit on the rear side of the aircraft if we got into trouble.

Here, you see Chief Master Sgt Samuel Davies, a boom operator on the KC-135R, shutting the side hatch before takeoff. I believe it is the aft escape hatch.

Try to envision his directions. He told us to do the following:

- Put on your parachute.

- Open the aft hatch. Stand facing it. Cross your arms, left arm over the right arm, and hold on to the side of the hatch with each hand.

- Cross your feet, again putting the left foot over the right foot.

- Twist your body so that you go out back first.

After I practiced this maneuver several times, he dropped the punch lines. He said the likelihood was high that the rear horizontal stabilizer would cut us to pieces once we left the aircraft! And, he muttered, no one bails out of a KC-135. He then told us he hoped a circumstance requiring us to bail out would not happen until after we had refueled our target aircraft. That was because there was a lot of fuel beneath the deck on which we were standing.

My heart was palpitating by this time! The Chief got his chuckles.

I’ll now walk you through the KC-135 mission I was on. For me, it was memorable.

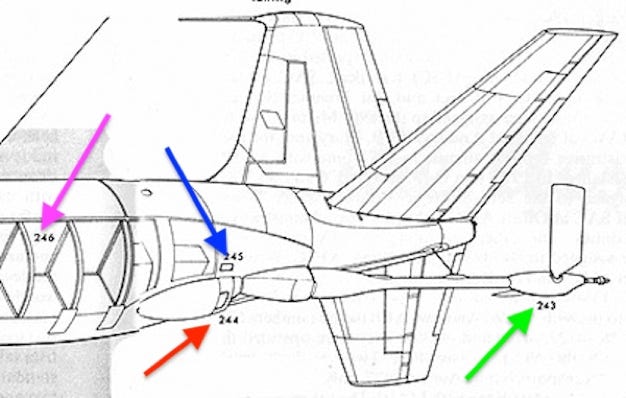

This is an excellent graphic view of the rear of the KC-135. The photos that follow are keyed to the graphic and show the points of interest presented by AirPigZ

The red arrow points to Nr. 244 to mark the boomer’s window through which to observe the receiving aircraft

The blue arrow points to Nr. 245, which is a side window that the boomer uses mainly to watch the receiving aircraft depart the area after disconnect, or the boomer can look at the receiver aircraft that has been waiting off the KC-135’s wing maneuvering into position for his turn to refuel.

The green arrow points to Nr. 243, which shows the boom in its stowed position. At the end of that boom, you can see the section tip that will telescope into the receiver aircraft and unload the fuel. Also, note a small wing from the boom on each side. These wings help the boomer fly his boom into position.

Last, note the pink arrow pointing to Nr. 246 to the far left of the graphic. It marks one of five underfloor aft fuel tanks. Four more underfloor forward fuel tanks are under the large cargo hatch between the cockpit and the wings. Altogether, these tanks can hold 200,000 lbs. of fuel, which equates to about 24,000 gallons US.

Above the floor is a substantial amount of cargo space that can be configured to carry passengers, cargo, or both.

The boom operator was prone to the far rear of the aircraft, operating the refueling probe, connecting to the target aircraft, loading it with fuel, and disconnecting in close coordination with the B-52 and KC-135 pilots to ensure a clean breakaway.

I was fortunate to lie on a mat next to the boom operator when we refueled the B-52, much like the guest flying on a mission. With some butterflies in my stomach, I was thrilled to have this view of the refueling process.

The boom operator is an enlisted member of the USAF trained for this job. The pilot, co-pilot, and navigator are all officers.

This is a photo of the boomer’s station. The large handle grip to the left is what the boomer uses to telescope the boom refueling probe into the receiver’s fuel receptacle.

My adrenalin was flowing. The first thing that stood out was that we were refueling a B-52 that was part of the 24-7 cycle of nuclear-loaded B-52s, ready to go in at a moment’s notice. Our mission was not a training mission. It was the real “McCoy.” Second, it was a nighttime mission. We were out over “someplace.” There was nothing out there that I could see.

Suddenly, seemingly out of nowhere, we spotted a B-52 nuclear bomber approaching. I was amazed at how the two aircraft found each other. It was remarkable that such a large aircraft came out of nowhere and eased on up to our KC-135. The B-52 looked small, and I could see its pilot and co-pilot.

I have Photoshopped a daylight photo here to make it look like night. I remember that it was far darker than this, almost pitch black. The B-52 had blinking lights on its wing tips, and there were, I believe, lights surrounding its receptacle.

I did not know it then, but there were lights under the boomer on the belly of the KC-135 that signaled to the receiving pilots which way to move to stay in the refueling envelope. If they were beginning to move out of the envelope, the lights shone yellow; if they were at the limits, they shone red.

They used predesignated refueling tracks, and of course, both crews planned their missions and communicated.

The boom operator did his thing with incredible professionalism, guiding his pilot and the B-52 pilot as he put the probe spot-on into the receptacle of the B-52 and then refueled him. I don’t remember how much fuel he gave him, but it was a lot. And it seemed like it only took a few minutes.

Then came some excitement. The boom operator coordinated the disconnect with both pilots. As I recall, the KC-135 would accelerate a bit and climb, while the B-52 was to decelerate a bit and drop down in altitude. That did not happen. When the boomer made the call for disconnect, the KC-135 accelerated and started a slow climb; the B-52 broke away, decelerated, and dropped down a bit but then suddenly increased his altitude and speed and smashed into the boom as the boomer was trying to withdraw it. It was not a tumultuous bang, but the two aircraft did collide a bit. The boomer said a few words under his breath and then gave instructions very professionally. I was impressed. I didn’t realize what happened until I heard the boom operator passing a little more than gas!

I’ll pause for just a moment here. I was a university senior on this mission and would become a USAF second lieutenant at graduation. This mission taught me an incredible lesson about the professionalism of the enlisted force and the massive responsibility they shoulder. As time passed, this lesson repeated itself and served me well.

A boom operator can be a young first-term airman or a chief master sergeant with many years tucked under the belt. Their job carries a lot of responsibility. They must qualify as loadmasters. The boomer inspects the equipment from start to finish, constantly checking it out. A sassy boomer will tell you they direct the tanker and receiver aircraft through the process.

Of course, the boomer’s pilots and those of the receiver aircraft are officers, so decorum must be maintained. Most KC-135 missions only require three crew: the pilot, co-pilot, and boomer.

The boomer computes and applies weight and balance data, procedures, and techniques. They ascertain fuel, personnel, cargo, and emergency and special equipment weight and balance and ensure their aircraft is loaded within specific safety limits. They have a ton of paperwork to document the data. They have to understand their tanker’s electrical and mechanical systems, flight theory, electrical, hydraulic, and pneumatic systems related to the in-flight refueling system, weight and balance factors, cargo tie-down techniques, minor in-flight maintenance, communications and emergency procedures, and using and interpreting diagrams, loading charts, technical publications, and flight manuals. So, this is no trivial intellectual pursuit.

I’ve canvassed research on the boomers and will highlight some interesting stories they tell.

Air refueling is a dicey business. Between 1958 and 2013, some 52 KC-135s were lost in accidents. Some reasons were a heavy weight on takeoff, structural failure in a thunderstorm, in-flight collision with B-52, starter explosion causing fuel fire during engine start, in-flight collision with F-105, two engine losses during takeoff, stalled during takeoff, nose tires blew, exploded at 13,500 ft., hard landing, engine fire, stalled in turn, landed on fire, high crosswinds, and burned ramp due to center wing explosion.

On November 6, 2006, Senior Master Sergeant (SMSgt.) Anthony Trenga, shown here, marked his 10,000th flying hour on the KC-135. It was a combat mission over Southwest Asia supporting air operations over Iraq. He, his pilot, Major Jason Luhn, and co-pilot Capt. Walter Ransom, all members of the Pennsylvania Air National Guard, launched on time and shortly after takeoff noticed that the cabin was not pressurizing. That required them to dump all their fuel and abort or try to devise a fix and press on. They needed cabin pressurization to reach cruising altitude, where their refueling operation was planned. Trenga recommended they try to fix the problem.

The pilots took the aircraft to 10,000 ft. so they could depressurize. They discovered that an auxiliary power unit (APU) door had not closed tightly. Once at 10,000 ft., Trenga cycled the door open and closed under the stress of listening to the noisy airflow through the APU. A further complication was that the aircraft was not as structurally stable when depressurized as when pressurized, so the heat was on. Despite the heat, Trenga got the door to seal.

As it turned out, there were heavy air attacks over Iraq that day, and the tanker was in high demand. SMSgt. Trenga had to make many adjustments to meet the demand, which he did. Oh, yes, Trenga was 53 then, which is another sign of “Old Guys Rule.”

The photo to the right shows a lineup at the gas station. The aircraft included the KC-135 Stratotanker, F-15E Strike Eagle, F-117 Nighthawk, F-16 Fighting Falcon, British GR-4 Tornado, and Australian F/A-18 Hornet. (U.S. Air Force photo/Master Sgt. Ron Przysucha)

The 131st Air Refueling Squadron (ARS), 157th Air Refueling Wing (ARW), an Air National Guard unit based at Portsmouth International Airport, took family members up as part of family appreciation to show them what their family members were up to when on a refueling mission.

The 157th ARW flew most of its refueling missions over New England to train its own and receiver aircraft crews. The 157th and 101st ARW at Bangor, Maine, comprised the Northeast Tanker Task Force, which supported the transatlantic air bridge for cargo and tactical aircraft transiting to and from Europe.

For this mission, they would fly two KC-135s. The mission was to refuel A-10 Warthog fighter aircraft, and the two KC-135s would allow them to refuel two A-10s simultaneously. They were scheduled to refuel over “Laser North,” a refueling box over the Mt. Washington area.

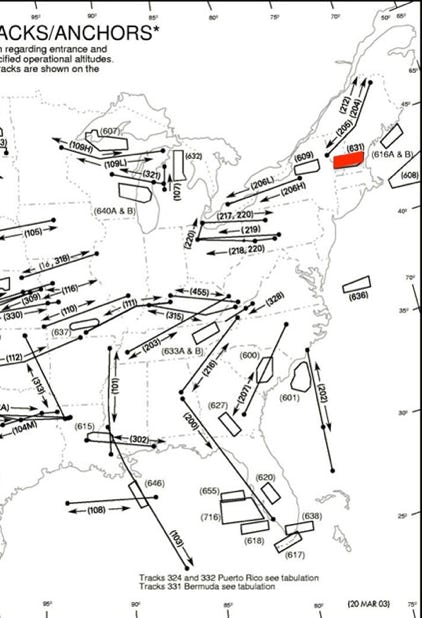

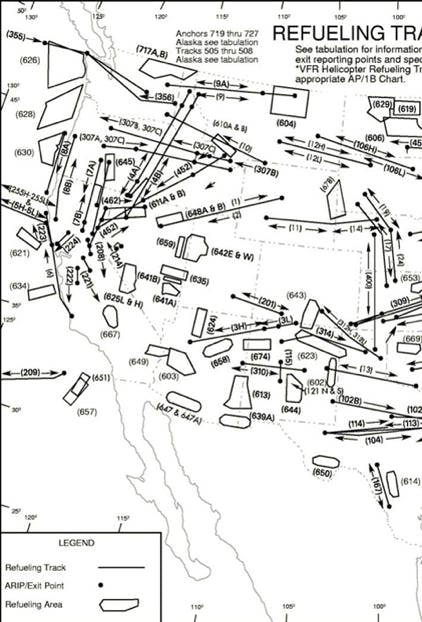

I want to pause for just a moment. The air-to-air refueling business is complex. I want to show you two maps displaying refueling tracks over the entire United States, first the western and then the eastern half.

I believe Mount Washington is in southwest Massachusetts, and I am guessing their refueling area was Nr. 631 on the map, highlighted in red. The weather was lousy. Nonetheless, KC-135 callsign Pack 61 heavy took off first, and Pack 62 followed. They flew at about 20,000 ft. and awaited a call by the A-10s that they had reached their Initial Point, at which time the boomer guided them into position. The A-10 is a slow aircraft, so the KC-135s had to slow down. That, in turn, created an issue for the boomer, who lost airflow over the boom wings, which in turn caused the boom to be sluggish when he flew the boom.

The family observers were tied into the headsets and amazed at how much radio chatter the fliers had to handle. Boston Center had to keep aircraft away from the refueling area, the pilots had to talk to each other, the two tankers had to talk to each other, and the boom operator had to talk to all of them, plus the A-10 pilots.

The KC-135s arrived on-station about 20 minutes after departure. Pack 62 flew slightly behind and above Pack 61. The A-10s carried the callsign “Rooster Flight,” and Boston Control said it had cleared Rooster into the refueling box. As the lead A-10 moved to Pack 61, he positioned himself 1,000 ft. below and awaited instructions from the boomer that would clear him for pre-contact. His wingman stood steady alongside the tanker’s starboard wing, waiting to be next. I need to interject an editorial note here. This was not a combat scenario, but there are situations in combat where fighters come up to their tankers and are all in a hurry to get fuel because they are running on fumes. So, these kinds of things can get very hectic.

The boomer cleared the A-10 in and plugged into the receptacle just in front of the cockpit on the A-10’s nose. In this case, they had some difficulty getting a good fit, so the A-10 would back off, come back, back off, and come back until the A-10 pilot and boomer felt the time was right. It was right, and the A-10 got his gas, dropped off, and lined up with the tanker’s port wing. The second A-10 moved into the pre-contact position and the beat goes on.

A man named Tracy, a retired military pilot operates a website called “About the Pattern - An aviation blog.” He has a great story online about air refueling the C-5 Galaxy strategic transport, known in the USAF as “Fat Albert.” In the photo he used, you can see the incredible difference in the refueling and receiving aircraft size! Holy moley.

I want to highlight some things he said.

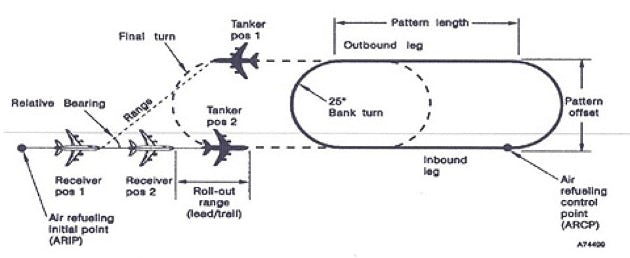

Part of a C-5 crew’s pre-flight mission planning is ascertaining whether they will be air refueling. If they need it, they notify the appropriate authorities, an air refueling track is set up and reserved for him, and a tanker is assigned to the mission. The air refueling tracks are already identified and include data on altitudes, navigation points to define the track, the air refueling initial point (ARIP), contact point (ARCP) and air refueling contact time (ARCT), communications plans, and the controlling agency.

Tracy said there are two ways to bring the tanker and receiver together.

One method is to establish a point to which each aircraft flies at a specific heading and altitude. The aircraft then line up and conduct business.

The more popular way is called “point-parallel rendezvous,” shown in the schematic presented by Tracy. The tanker takes off, flies directly to the ACRP, and enters a holding pattern. The receiver flies to the ARIP at the planned altitude and speed. For a C-5, the refueling speed is 252 knots. The two aircraft established communications 15 minutes prior to the ARCT. Once done and each aircraft has positively identified the other, the tanker advised he has accepted responsibility for separating the two aircraft, relieving the Air Traffic Control (ATC) system of that task. ATC clears the two aircraft to commence their refueling operation.

I don’t want to go into the details of how each aircraft maneuvers other than to say they have a checklist of things they must do to align with the receiver behind the tanker. This requires the tanker to swing out of its holding pattern and maneuver itself in front of the receiver, which requires a lot of calculations.

Once lined up, both aircraft should see each other, though this can be difficult if the weather is bad. The receiver's pre-contact position is one mile behind and 50 feet below the tanker. Visual acquisition by both aircraft must be made before the pre-contact position or the mission will be aborted, and the receiver will be diverted to an alternate airport.

Once in the pre-contact position, the C-5 must run through a checklist to open the air refueling door and check the fuel systems. The C-5’s air refueling receptacle is just aft the cockpit on top of the aircraft fuselage. The C-5 pilots have loads of lights to watch to ensure the refueling operation runs smoothly. When the C-5 gets into the center of his receiving envelope, the boom operator flies the boom toward the receptacle opening. The receiver gets into position, and the boom operator extends the inner portion of the boom, sticking the boom into the receptacle. Latches on the C-5 then close to secure the boom in the receptacle. Once latched, the fuel begins to flow.

Should the C-5 get out of the envelope, there is an almost automatic disconnect sequence. There is also an emergency “breakaway” procedure that the boomer or the receiving pilot can initiate. The most common cause for this is if the two aircraft get too close to each other. During the breakaway, the tanker hits the throttles to full power and climbs to the top of the refueling block, usually about 1,000 ft. higher. At the same time, the receiver reduces power to idle and descends to the bottom of the refueling block, about 1,000 ft. lower. Once everyone has checked out their aircraft and there has been no damage, they go through the refueling process again.

Tracy’s report says the C-5 pilot flies the aircraft manually while the KC-135 is on auto-pilot. Should you read Tracy’s report, you will see that the design of the C-5 is such that it can create some bow forces that cause the KC-135’s tail to lift. Changes had to be made to the KC-135 to accommodate this issue.

Tracy mentions that this entire exercise is one of formation flying. Many forces bear on the aircraft that require keen flying sense by the pilots and the boomer. He commented in one instance that the C-5s were painted black; they were flying a nighttime mission with no moon, and there was a cloud cover, so nothing on the ground was visible. When the C-5 showed up, it seemed to the boomer that this huge black aircraft came out of nowhere, and he sensed that it would smash into the KC-135. So, the boomer called for a breakaway, which was not necessary. He had never refueled a C-5 before. Fortunately, he had his instructor with him, and the instructor brought everybody back together, and they completed the refueling mission.

Tracy talks about doing all this with thunderstorms all around them. I commend his stories to you.

Capt. T.W. Sherman, Jr.’s story, “The Tough and Ticklish Job of Air Refueling,” was published in the March 1961 edition of Popular Mechanics. Sherman was a B-52 pilot and said,

“Any SAC (Strategic Air Command) bomber pilot will tell you that he sweats out air refueling more than anything else. It takes all the skill and guts he’s got to wrestle the big bomber in behind a tanker where a slip can mean a flaming disaster.”

He quoted a tanker pilot saying, “You’d never get me back there to watch a refueling. It scares the hell out of me!”

Sherman tells of his first air refueling mission. The KC-135 was over Montpelier, Vermont, with 30,000 lbs. of fuel for Sherman’s B-52. His radar operator reported getting the tanker’s beacon at 180 miles. The beacon puts a code on the radar operator’s scope, which enables him to identify the aircraft as his KC-135. The radar operator is a deck below the two pilots and cannot see out of the aircraft.

Soon after, the B-52 is within 80 miles and commences its descent. Sherman banked the B-52 to meet up with the tanker. He commented the bomber seemed hard to handle at the time. Sherman slowed down to 250 knots. The boomer on the tanker reported that the boom was down and that the tanker was ready for contact. Sherman pulled in a little closer and spotted a suite of red and green lights controlled by the boom that told him to fly up or down fore or aft.

Sherman was well aware of the challenge coming. He had to put his B-52 into the envelope, which is 12 feet long, 14 feet high, and 21 feet wide. He knew he had to keep his bomber inside that envelope. Making this even more challenging was that the KC-135 ahead of him produced a slipstream that created a downdraft in the area of contact. Sherman had to stay in the correct position or risk a downwash that would cause his nose to “zoom up.” If that happened, he had a procedure to execute immediately to avoid a collision. Under normal circumstances, this massive B-52 and the fuel-laden KC-135 are within 25 ft. of each other.

Sherman eased the B-52 closer, and the boomer raised the boom to clear Sherman’s windshield. Sherman felt the effects of turbulence and downwash and felt like the KC-135 was bobbing around all over. The boomer kept talking to Sherman, giving directions such as, “Forward ten, up four, forward five, up two, stand by for contact. Contact tanker.” Then the boomer noted Sherman was going too fast and told him, “Back two, back four, disconnect.”

Sherman tried twice, but each time was still going too fast. He commented,

“I’m dripping sweat. My breath is rasping against my oxygen mask.”

His instructor pilot took the wheel and demonstrated to Sherman how to act like the envelope had walls he could not penetrate. The instructor then told him to try it again. Sherman got it in perfectly and started taking on 600-900 gallons per minute of fuel. They stayed hooked for six minutes, which Sherman described as “long minutes.”

Unfortunately, Sherman began over-controlling his bomber, and they disconnected. He brought her in again, connected, and took on more fuel. The tanker pilot told him he had taken 20,000 lbs. and had 10,000 more. Sherman, saying he employed his “last reserves of strength,” pulled up again, connected, and took on the final 10,000 lbs.

One can only imagine what was going through the boomer's mind during this flight. From Sherman’s description, he was very professional, always guiding Sherman. What might have been said under his breath, well, we’ll leave it there.

Another moment to pause. We Americans like to talk in terms of gallons, not pounds of fuel. The problem is that different countries define what comprises a gallon differently. For example, a US gallon is 0.82 of an Imperial gallon. And, of course, many countries use liters. So aviators switched to pounds of fuel as the measure. The tricky part is if the crew has to convert whatever their measure is on the ground to pounds. This conversion has to be correct, or there is a risk of running out or carrying too much.

John Yang wrote, “Refueling at 25,000 ft.”, a story about a refueling mission for Secretary of Defense Rumsfeld’s E-4B aircraft, a customized B-747. Yang was aboard the E-4B. Three KC-135 tankers were employed. The E-4B had already been aloft for 7.5 hours and needed fuel.

The tankers flew in formation, their altitudes about 500 ft. apart, one “on top” the other. The mission was conducted at 25,000 ft. altitude. As the E-4B approached the first tanker, the E-4B pilot took manual control of his aircraft and maneuvered into position. Yang estimated that it was about 12 ft. above and just ahead of the E-4B when they pulled up to the tanker. As an aside, those measurements seem exaggerated when one looks at the photo above. The tendency is to look at the distance of the boom. But look carefully at the distance between the E-4B’s cockpit and the horizontal stabilizers and tail of the tanker; they’re pretty darn close.

Yang described the fill-up in terms we have already gone through. What he noted was new for this report: As the E-4B took on fuel, it got heavier and wanted to fly lower and slower. As the tanker emptied fuel, he got lighter and wanted to fly faster and higher. Pilots of both aircraft had to plan and compensate for that. Yang then remarked that the boom had a bad seal and jet fuel began spraying all over the windshield of the E-4B. The wipers cleaned off a lot, but visibility was reduced, such as in a storm. During this first refueling, there was an accidental disconnection, and the E-4B had to maneuver back into position.

Yang said it was “a rather bumpy ride, a bit like riding waves on a choppy sea. The pilots call it ‘dolphining’ and describe it by arcing a hand up and down like a dolphin playing in the waves.”

Once the tanker was empty, the crew repeated the same routine twice with the other two tankers.

I have a friend who has talked to me about the tanker and receiver aircraft flying in a race-track orbit, where they would turn together at the end of the race track to head in the other direction and continue refueling. He flew aboard an RC-135 aircraft and said refueling in a turn was the most intimidating part of the operation.

A flight of USAF F-4C Phantom fighter bombers refueled from a KC-135 tanker aircraft in the 1960s before making a strike against communist targets in North Vietnam. The Phantoms were fully loaded with 750-pound general-purpose bombs and rockets. You can bet these guys were happy to see their tanker on the way home after burning off nearly all their fuel on their attack runs.

Some receiver aircraft are fitted with probes and cannot be refueled using the boom. The probes on these aircraft fit into a drogue. The KC-135 uses a shuttlecock-shaped drogue attached to and trailing behind the flying boom. The trick is for the receiver aircraft to fit its probe into the drogue to obtain fuel.

Here, you see a European Tornado fighter using the drogue-probe system. When he approaches to refuel, he activates his probe, which extends from his fuselage, and then sticks it into the drogue.

Some KC-135s have special pods mounted on their wing tips, allowing a single KC-135 to refuel two aircraft simultaneously. The next photo shows an Australian F/A-18 being refueled with the probe-and-drogue refueling system.

Walter J. Boyne wrote an article entitled “The Young Tigers and Their Friends,” published in the June 1998 edition of Air Force Magazine. He wrote,

“The heartfelt phrase ‘Thanks, that's a save!’ was heard more than 500 times during the Vietnam War as hardworking ‘Young Tiger’ crews of KC-135 tankers moved into harm's way, delivering salvation to strike aircraft perilously low on fuel. Ironically, many of those saves were never officially recorded simply because they occurred when the tankers left their normal orbits to enter enemy airspace, in violation of standing instructions.”

He wrote about Major John H. Casteel’s KC-135 “saving six Navy aircraft with a complex and totally unscheduled refueling.”

Casteel’s mission was scheduled to refuel two F-104 Starfighters using the drogue adapter he had installed on his boom ship. That mission came off without a burp.

Then an emergency call came in saying two Navy KA-3 tankers from the carrier USS Hancock, which also needed the drogue, were running out of fuel. The first KA-3 “Whale” hooked up with only three minutes of fuel. Technical problems precluded him from using his refueling tanks. Then came the second Whale, and he got his goodies, too.

Once done, another emergency call said two Navy F-8 “Crusader” fighters were approaching fuel starvation, and he refueled them. Colin Bakse, in his book Airlift Tanker: History of US Airlift and Tanker Forces, adds a little to the Boyne version (search the link for Casteel). Bakse said the F-8s were so low that they took fuel from the KA-3s while the KA-3s took fuel from the KC-135!

Casteel was just about ready to return to base (RTB) when all of a sudden, two Navy F-4 Phantoms from the carrier USS Constellation showed up on the scene; neither had enough fuel to return to their carrier, but the problem now was Casteel’s KC-135 was also running low. So Casteel steered his KC-135 toward Danang, not his home base, told the F-4s to follow, and refueled them on the way right up to his landing. On landing, he had only 10,000 lbs. of fuel left. The boomer was MSgt. Nathan C. Campbell, no doubt one tired GI when they got on the ground.

Boyne wrote that the fighters wanted to carry as much ordnance as possible, so they would refuel to conduct their runs shortly after takeoff from home base. They might have so many targets that they would exhaust most of their fuel trying to hit them. They all would need post-strike refueling. They often received battle damage and were leaking fuel, so they needed extra.

Boyne says the KC-135s in Indochina had four primary and two secondary missions.

First, they had to support the Guam-based B-52 Arc Light bombing missions over North Vietnam.

Next came the “Young Tiger” missions supporting fighters. Whereas the Arc Light missions were predictable and easy to execute, the fighters were all over the place and often endured fuel starvation challenges that were not at all predictable.

One that bears particular attention is refueling post-strike aircraft, especially F-4s and F-105 Thuds. The pilots had just endured exhausting and hair-raising raids against heavily defended targets in North Vietnam, and they had to marry up with their tanker when their knuckles were still white from their attacks and enemy attacks against them.

Ralph Wetterhahn, writing “Dead Stick at Dong Ha,” conveyed the story of three USAF F-4s targeted at “JCS-16,” a high-priority bridge not far from Haiphong Harbor designated by the Joint Chiefs of Staff. The F-4s received constant MiG and Surface-to-Air-Missile (SAM) warnings from monitoring aircraft over the Gulf of Tonkin. As they approached their target area, they saw plenty of flak in front of them and received a SAM warning. They were running at 500 knots at 4,500 ft above rolling terrain. One of the pilots commented, “Two minutes prior, we had been relatively comfortable. Now our flight suits were drenched with sweat, gloves soaked, and he was holding on to a slippery stick with a ‘vise grip.’” They then attacked their target. So you can imagine what kind of state of mind they might have been in had they used a tanker on the way home.

Mission planning for all these fighter missions was often done “on the run,” good ol’ GI “seat of the pants.”

The next priority was refueling for the SR-71 reconnaissance aircraft, which required special JP-7 fuels carried only by KC-135Q aircraft. The final primary mission was to refuel electronic reconnaissance and airborne radio relay aircraft.

Boyne said,

“Curiously, the very success of the tankers in making a difficult task seem ordinary resulted in their receiving less credit from the Air Force and the public than should have been the case. An analysis of even a routine refueling operation shows manifest hazards. A 313,000-pound aircraft, flying at 26,000+ feet, at 300 knots, and carrying 100,000 pounds of fuel is perhaps not of itself impressive, but put that same aircraft within 40 feet of an even bigger aircraft, weighing 400,000 pounds, join them with a refueling boom, and you have a hazardous situation. Then try doing it at night, in foul weather, under radio silence, and in company with a mass formation of 50 other aircraft doing the same thing within a few square miles, and the hazardous situation becomes genuinely explosive.

“Alternatively, have the tanker off-loading fuel to a gaggle of fighters already past the critical fuel state, well inside enemy territory, and vulnerable to MiGs, flak, and SAMs.”

You must read Boyne’s article. I want to relay one war story he addresses.

Major Alvin L. Lewis was flying his KC-135 in May 1967 through violent thunderbusters and had to find two F-105 Thuds that were critically short of fuel. Lewis saw them in a clear area and “put his tanker into a 20-degree dive to position himself in front of the first fighter, which had already flamed out.” This is incredible.

The Thud was heading toward Earth, and the pilot was getting ready to eject. Still in his dive, the tanker got himself in front of the F-105, hooked him up, and brought him enough fuel so the pilot could restart his engine. After transferring this small amount of fuel, the tanker increased his dive angle in front of the fighter to 30 degrees to create enough airflow through the fighter’s intakes so the skipper could start his engines. He then cared for the second guy, and all hands made it home safely.

Let’s hope the Officers’ and Enlisted men’s clubs were open when they all got home.

There is a short video on YouTube, shot from the cockpit of a C-17 strategic transport while refueling from a KC-135 in a thunderstorm over the Black Sea. I commend this to you. Several times, the C-17 pilots cannot even see the KC-135 during the refueling operation. And, of course, they’re bouncing around quite a bit --- nerves of steel.

Finally, Boyne points out that, on average, only 88 KC-135s were available during the Indochina War. These aircraft flew 179,040 sorties and offloaded 8.2 billion pounds of fuel, which is truly remarkable.

Stories abound, and I could go on for days relating them. A good way to put on a wrap is with some Air Force tanker jargon,

“Still passing gas.”

“Nobody kicks ass without tanker gas ... nobody!”

Click to zoom graphic-photo