DUTY, HONOR, COURAGE, RESILIANCE

Talking Proud: Service & Sacrifice

Joe Darrigo and the Big Surprise

Credit: Marine Corps Staff Sgt. Chase Baran

A Marine platoon landed at Inchon, South Korea, on September 15, 1950. They came by boat from San Diego. While at rest after the landing, the top sergeant came to his lieutenant and asked, "Where are we?" The lieutenant answered, “Why hell, sergeant, we're in Korea." The sergeant responded, "How do you know?" The lieutenant, now a Marine Corps colonel, told me this interchange still bothered him. The fact was he did not know for sure. The lesson: Nothing is as it seems.

As told to me by Colonel Peter F.C. Armstrong, USMC

___________

Army Captain Joseph Darrigo was the only American on the morning of June 25, 1950, on the 38th parallel separating the Koreas. He was known as “Uncle Pip,” just “Pippi” to residents of his hometown, Darien, Connecticut.

Darrigo was the first American to observe the North Korean People’s Army (KPA) invasion of the Republic of Korea (ROK). He was a veteran of the Normandy Invasion of WWII, having landed at Omaha Beach, so he was no rookie. But on this day, he was the only American military man on the 38th parallel.

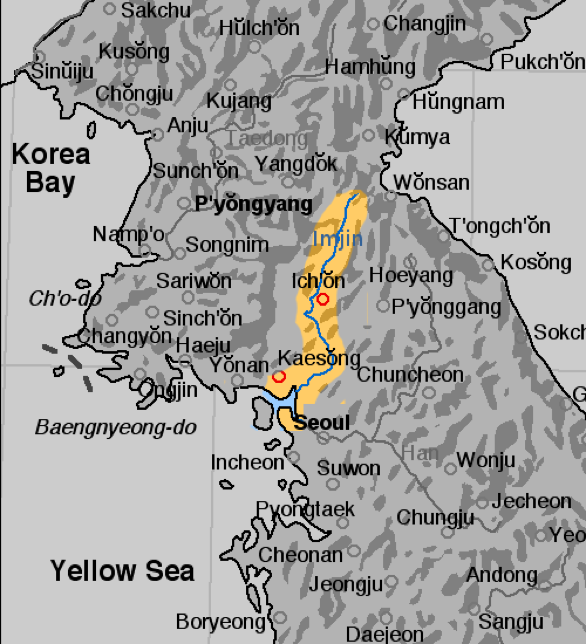

Captain Darrigo was on observation duty at Kaesong, on the border dividing North from South Korea, within spitting distance of the 38th parallel. He was the Assistant Adviser to the 12th Regiment, one of three regiments of the 1st ROK Army (ROKA) Division, and a part of the Korea Military Advisory Group (KMAG) to the ROK.

In typical GI fashion, I have seen veterans refer to KMAG as "Kiss my ass goodbye."

Bruce Bechtol Jr. of Angelo State University has identified two major invasion routes into the ROK that were used “throughout time, when invaders have needed to attack into the heart of Korea, and thus Seoul. These two corridors have been the routes where large numbers of troops could traverse through the mountains.” They are the Kaesong-Munsan Corridor and the Chorwon Valley Corridor.

Darrigo lived in quarters just northeast of Kaesong, the ancient capital of Korea. Today, Kaesong is in the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea. But back then, it was just a heartbeat south of the 38th parallel, the dividing line between north and south, and therefore in the American zone.

Holding to tradition, the KPA attacked through both major corridors.

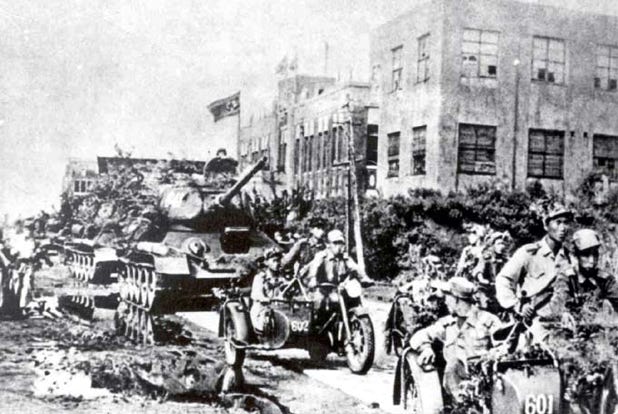

In Korea, it was in the early morning, about 4 am, June 25, 1950. It was mid-afternoon on June 24 in Washington. It was raining, Darrigo was in bed, and he heard loud noises like thunder. He quickly concluded it was weapons fire, some of which was hitting his home. He and his Korean houseboy jumped into a jeep, drove to the town center, and saw a train arriving with perhaps an entire regiment of KPA forces. The train appeared to have slid into town under the cover of the heavy artillery fire pounding ROKA forces along the parallel.

Darrigo decided he could not reach his ROKA 12th Infantry headquarters and determined Kaesong was unsafe. He was right. Kaesong fell at about 9:30 am.

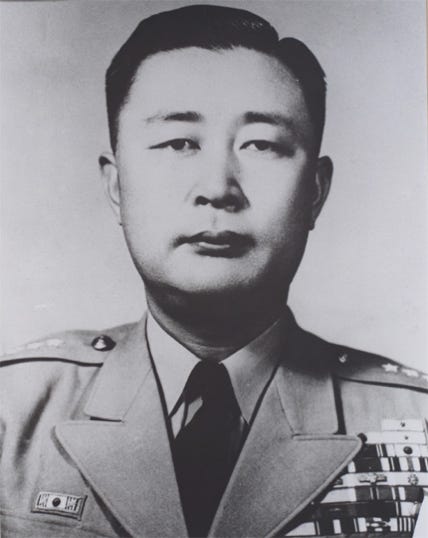

So he drove south across the Imjin River to the headquarters for the 1st ROKA Division, Colonel Paek Son-yop, 29, in command. Paek was a Japanese Manchurian Military Academy graduate, an officer in the Japanese Army during WWII, who returned to Korea after evading Soviet capture. He was a dedicated anti-communist. He was called "Whitey" by the Americans. During the Korean War, he distinguished himself as one of the ROKA's best fighting generals and ultimately became the Army chief of staff twice.

However, this was a surprise attack for his men, and the KPA was about to overrun his headquarters. General Paek wrote his memoirs, From Pusan to Panmunjom, about the war's beginning.

He attended a senior officers course in Seoul and received the call at about 7 am. His job was to protect Seoul. His force numbered about 10,000, and the Kaesong corridor was his area to defend. He had only been in command of the 1st ROKA Division since April 1950 and had spent much time attending a senior officer school instead of being with his division. In his memoir, he agreed with General Omar Bradley that this "was absolutely the wrong war, and its timing could not have been worse." That said, he had been briefed by the ROKA G2 (Chief, Intelligence) in mid-June that "North Korean movements are abnormal. An attack is possible."

After receiving the call, the best he could do was get to the ROKA headquarters in Yongsan, Seoul. Upon arrival, General Chae ordered him to get to his division. General Chae also ordered his 2nd and 7th Divisions to counter-attack. The 7th Division was on the 1st Division's eastern flank. It was Sunday morning, many troops were on leave, and regiments needed to be positioned in defensive locations useful for a counter-attack.

Col. Paek went to Lt. Colonel Lloyd H. Rockwell's quarters. Rockwell was the chief KMAG advisor to the 1st ROKA Division and had a jeep. Rockwell had not heard about the invasion. Colonel Paek grabbed the jeep, raced to Susaek, his division headquarters just north of Seoul on the Han River, and arrived around 9 am.

His 12th Regiment was responsible for Kaesong, and the regiment was out of communications, located north of the Imjin River (in yellow). The 13th Regiment near Munsan was fully engaged with the KPA. His 11th Regiment was in reserve at Susaek, recalling troops to reinforce. Only 50 percent of the 11th was available.

Col. Rockwell joined Paek at his headquarters but told Paek he had to leave as KMAG had been ordered to withdraw. This shocked Colonel Paek, as the Koreans had come to rely on KMAG for all their logistics. It now looked like the ROKA was alone.

The 11th kept the KPA from crossing, but the 12th could not get back across the river. In the meantime, two KPA divisions and a tank brigade were headed for Uijongbu to the east, defended by the 1st Regiment of the 7th Division.

Colonel Paek's division was defeated and forced to retreat to the south.

President William Clinton spoke at the observance of the 50th Anniversary of the Korean War held at the Korean War Memorial in Washington, DC, on June 25, 2000. Capt. Darrigo was at the observance, and Mr. Clinton recognized him, saying,

“The only American there that day was a 31-year-old Army captain and Omaha Beach veteran named Joseph Darrigo. He was awakened by what he thought was thunder. But when the shell fragments hit his house, he ran half-dressed to his Jeep and drove. Within half a mile of the local train station, he couldn't believe what he was seeing: a full regiment of North Korean soldiers getting off the train. Now, he later recalled, ‘Over 5,000 soldiers came against one person, me.’

Captain Darrigo escaped that day. He went on to serve another year in Korea before an illness brought him home. Time has slowed him down some, but not much. And we are honored that he could be with us here today.

“I'd like to recognize Captain Joseph R. Darrigo. Please, sir, stand.”

The Hartford Courant reported,

“Darrigo was the only living soldier Clinton recognized Sunday. His recognition was fitting because of its understated nature, because its hero was not someone plastered with medals or surrounded by cameras. Darrigo seemed like so many of his colleagues, a good soldier from a forgotten war that is just now inching back into the national consciousness at a seminal time when the United States told the world it would and could stand up to communism.

“These veterans Sunday were true to form. No one was embracing. No one was eager to go on and on with war stories. Some held umbrellas to keep the sun away. The military had set up 10,000 chairs; most were empty. The ceremony itself went off on time, dignified and free of celebrities and fanfare.”

When Capt. Darrigo woke up to explosions on June 25, 1950; there were no US ground combat forces in the ROK.

The 8th US Army was on occupation duties in Japan following WWII. Its four Army divisions were the closest to Korea but were not combat-ready. The 8th Army commander, Lt. General Walton “Johnny” Walker, sent three of his four divisions to the ROK piecemeal as fast as possible.

The invading KPA forces pushed the US 8th Army’s three divisions and the remnants of the ROKA to below the Naktong River around Pusan in southeastern ROK, which came to be known as the Pusan Perimeter. The Naktong was a natural barrier, and the Allied forces held for six weeks of fierce fighting.

US forces did an end-run and landed at Inchon near Seoul. Those in the Pusan Perimeter fought their way out and battled across the 38th parallel border into North Korea and to the Yalu River border with China. China then invaded and pushed the Allies to positions south of the 38th parallel.

The Allies then pushed their way back to the 38th parallel, and the Korean War became a stalemate until an armistice was reached on July 27, 1953. There has been no peace treaty. The ROK and DPRK are technically still at war.

The historical consensus is that North Korea sent anywhere from 70,000 to 90,000 KPA troops into the ROK in an invasion that surprised the ROK and US political and military establishments.

It’s now 74 years since Capt. Darrigo woke up to the KPA invasion of the ROK. The US lost about 37,000 Americans during the Korean War, with over 92,000 wounded and 8,000 missing.

It is worth examining 1945 to 1950 and assessing why the KPA invasion surprised American political and military entities.

Katherine Weathersby of the Woodrow Wilson Center wrote “The Korean War Revisited.” She reminds us,

“The end of the Cold War has not done much to reduce the long-simmering hostility between North and South Korea.”

She is correct. The question is whether our leaders have taken heed.

On January 15, 2024, DPRK leader Kim Jong Un told the 10th Session of the Supreme People’s Assembly (SPA) that reunification of the DPRK and ROK was no longer possible. He said they were to be seen as two separate countries.

This announcement marked a significant change from his father and grandfather's reunification objective. He said should war break out on the Korean peninsula, then the DPRK's aim should be to occupy, subjugate, and reclaim the ROK completely. In short, the DPRK should annex the ROK as part of its territory.

Furthermore, Kim Jong Un declared in 2022 that the DPRK should become a world nuclear power.

So much has changed since the KPA invasion. Let’s look back to 1950 when the KPA pulled off a stunning invasion of the ROK, surprising and stupefying the American political and military leadership. The question I pose to you is: Why so surprised?

The US Demobilizes

According to the National WWII Museum, Truman demobilized American military forces “at a blistering pace,” from eight million soldiers in 1945 to 684,000 on July 1, 1947. “Between September and December 1945, the Army discharged an average of 1.2 million soldiers per month.”

The total number of active divisions dropped from 89 to 12. Four of these 12 Army divisions were in Japan in 1950, serving as an occupation force and not combat-ready.

Donald Carter, writing The US Army Before Vietnam 1953-1956, said,

“The Korean War found the U.S. Army unprepared for combat. President Truman’s draconian budget and his refusal to allow the Army to achieve its authorized strength had reduced most units to hollow shells.”

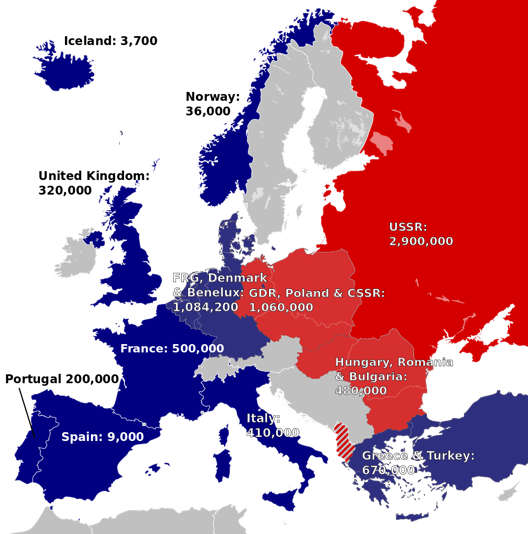

All US Eyes on the USSR

Donald Carter wrote,

“Almost as soon as the documents marking the surrender of Germany in World War II were signed in May 1945, the ties that bound the two major wartime allies—the Soviet Union and the United States—began to disintegrate.”

To make matters worse, the Chinese communists took over China. The blame went to President Truman and Secretary of State Dean Acheson for losing China to the communists. The fear here was communism more than fear of the Chinese.

Since the close of WWII and up to 1950, the US has been fixated on the Soviet Union and, to a lesser degree, on communist China, and with good reason. Communism took hold in Russia after WWI. After WWII, communism was everywhere. Its first significant wave was in Europe: Albania, Yugoslavia, Bulgaria, East Germany, Romania, Poland, Czechoslovakia, and Hungary. It also took hold in Asia: China and North Korea.

Furthermore, the CIA has said,

“The first wide-scale Communist action to seize control of Southeast Asia began in 1948 … (By 1949) the Communists launched rebellious offensives in four countries: Burma, Indonesia, Malaya and the Philippines.”

The UN and the Soviet Union were two central features of US foreign policy in 1950.

The US Department of State said in 1950,

“It is a primary objective of the foreign policy of the US to ensure the security, freedom, and well-being of the American people. These in turn depend in part upon the security, freedom, and well-being of other peoples, and upon orderly relations among nations. The principal organizational structure of the community of nations—and the only one designed to be world-wide—is the United Nations … It is in our interest to maintain (the UN) as an institutional structure through which sovereign nations may collaborate in collective endeavors.”

In remarks by the Secretary of State on February 16, 1950, Dean Acheson said,

“The only way to deal with the Soviet Union … is to create situations of strength … We are struggling against an adversary that is deadly serious. We are in a situation where we are playing for keeps. Moreover, we are in a situation where we could lose without ever firing a shot.”

Secretary Acheson explained,

“The US must be prepared to wherever possible all threats of the Soviet Union. It will not always be possible to anticipate where these threats will take place, and we will not always be able to deal with them with equal effectiveness.”

Korea Divided

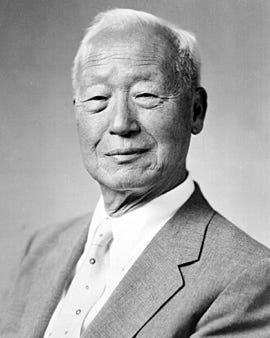

Kim Il-Sung (left), the leader of the DPRK, and Syngman Rhee (right), the leader of the ROK, both had reunification of the peninsula high on their “to-do” lists. However, the reunification of Korea was not part of the US-USSR agenda.

The State Department Historian has written,

“Neither of the Cold War antagonists would permit its Korean ally to be threatened by unification. The Soviets supported Kim Il Song in the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea (DPRK) in the north; the United States backed Syngman Rhee in the Republic of Korea (ROK) in the south.”

One can conclude that the US State Department saw reunification as a threat. Let’s examine more background.

Japan ruled Korea from 1910 to 1945. Before that, it was a protectorate of China and ruled by a succession of dynasties. Historically, outsiders, mainly Chinese and Japanese, occupied the Korean peninsula, the latter occupying Korea before and during WWII. Koreans rebelled against the Chinese and the Japanese. One might have thought that the Japanese surrender to end WWII would have offered Koreans their freedom. Not so.

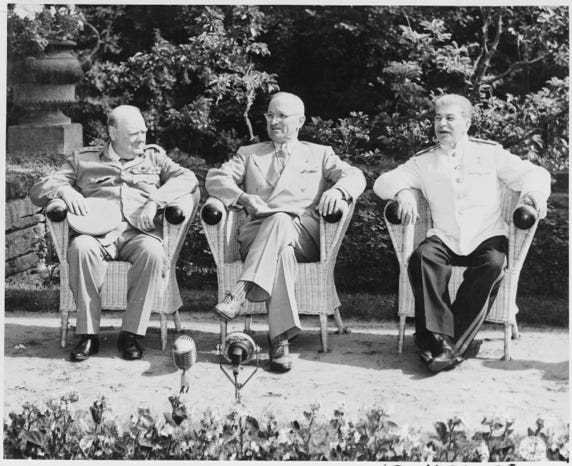

The leaders of the US, USSR, and Britain met in February 1945 at the Yalta Conference to discuss the way forward during and after WWII. The war ended in May 1945 in Europe and September 1945 in the Pacific.

James Matray wrote in the Journal of American-East Asian Relations that US President Roosevelt and Soviet leader Stalin agreed at Yalta in February 1945 to establish a four-power trusteeship for Korea: US, USSR, Britain, and China (the Republic of China, ruled by Generalissimo Chiang Kai-shek). Theoretically, the objective was to pave the way for an independent Korea.

FDR died in April 1945. President Truman and Stalin avoided discussing the future of Korea at the Potsdam Conference of July-August 1945, effectively letting this four-power trusteeship dither.

Stalin entered WWII in the Pacific at the 11th hour, on August 8, 1945, between the US bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. The US did not like this Soviet intrusion because all hands knew the Soviets would seize as much territory as they could when Japan surrendered. That’s what they did in Korea and the Kurile Island chain.

On August 13, 1945, the US Joint Chiefs of Staff (JCS) appointed General Douglas MacArthur, USA, to receive the Japanese surrender.

The plot thickened in mid-August 1945. US officials decided that there would be two zones of occupation of Korea, the US and Soviet, divided at the 38th parallel. National Geographic has said Colonel Dean Rusk and Colonel Charles “Tic” Bonesteel “were assigned to identify a line of control that both the US and Soviets could agree to.” That was the 38th parallel. It would separate the US and Soviet occupation zones.

The US JCS confirmed that decision, and the Soviets agreed as well. That slammed the door shut on the four-power trusteeship.

Kim Koo led a Korean Provisional Government in Chungking, China, during the war. Dr. Syngman Rhee was its representative in the US. When Japan surrendered on September 2, 1945, the Provisional Government of Korea (PRK) was organized based on earlier work done during August to establish local committees throughout the peninsula to prepare for Korean independence. The US arranged for the provisional government members to return to Korea in late September 1945.

When the Soviets entered Pyongyang on August 24, 1945, they identified the People’s Committee there and quickly plugged the top positions with those friendly to the Soviet Union. Kim Il Sung became the leader in Pyongyang.

General MacArthur selected Lt. General John R. Hodge, commander of the US Army XXIV Corps, to occupy Korea. This corps participated in the invasion of Okinawa and came to Korea from there. The codename assigned to the US occupation of Korea was “Operation Blacklist Forty.” It involved 45,000 US troops. MacArthur warned Hodge that the Soviets might already be in Seoul; if so, Hodge was to take over Seoul nonetheless.

General Hodge established the US Army Military Government in Korea (USAMGIK) when he arrived. The US was not prepared to govern southern Korea. In October 1945, Hodge created the Korean Advisory Council and appointed members favorable to the US.

General MacArthur told the Korean people on September 7 that the US was establishing military control over all of Korea south of the 38th Parallel. The proclamation said,

"Having in mind the long enslavement of the people of Korea and the determination that in due course Korea shall become free and independent, the Korean people are assured that the purpose of the occupation is to enforce the Instrument of Surrender and to protect them in their personal and religious rights. In giving effect to these purposes, your active aid and compliance are required.... All persons will obey promptly all my orders and orders issued under my authority. Acts of resistance to the occupying forces or any acts which may disturb public peace and safety will be punished severely."

General Hodge appointed Maj. Gen. Archibald V. Arnold, commander of the U.S. 7th Division, the initial occupation force, as the Military Governor of South Korea on September 12, 1945. The State Department tasked Mr. H. Merrell Benninghoff as General Arnold’s political advisor. On September 15, Benninghoff complained to the State Department that they had no information on US policy toward Korea as it looked to be divided, and the staff was far too small, with too few competent people.

Thus, the history of foreign occupation of the Korean peninsula continued after WWII. This time, the occupiers were the Soviets in the North and the Americans in the South.

On October 17, 1945, MacArthur received a directive from Washington about US policy toward Korea,

“(The) ultimate objective (was) to foster conditions which will bring about the establishment of a free and independent nation capable of taking her place as a responsible and peaceful member of the family of nations. In all your activities you will bear in mind the policy of the United States in regard to Korea, which contemplates a progressive development from this initial interim period of civil affairs administration by the United States and the U.S.S.R., to a period of trusteeship under the United States, the United Kingdom, China, and the U.S.S.R., and finally to the eventual independence of Korea with membership in the United Nations organization."

So, the four-power trusteeship was back on the table. But not for long.

Messrs. Kim Il-Sung and Sungman Rhee arrived in mid-October 1945.

The Moscow Conference of Foreign Ministers from the US, USSR, and Britain was held in December 1945. The agreement reached at this conference is a little complicated.

A Joint US-USSR commission was drawn from the commands of the South and the North. The text uses the word “commands,” which I interpret to mean military commands.

This Joint Commission was to “assist in the formation of a provisional Korean government.” The commission was to prepare its proposals for setting up that provisional Korean government, which were to be presented to the four-power trusteeship. However, the US and USSR would have to make the “final decision.”

Once the provisional government was formed, the Joint Commission would consult with it and provide its proposals for a four-power trusteeship for Korea for up to five years.

US and Soviet officials met on January 16, 1946, and met until February 5. The US position was to integrate the two zones, while the Soviets wanted them kept separate. General Hodge reported that it appeared the two zones could not be reunited unless the entire peninsula was communist. The Soviets launched a propaganda campaign asserting the US was preventing Korean unification and independence.

By October, the Soviets withdrew from the Joint Commission, and on October 11, 1946, withdrew their Russian liaison detachment from South Korea. The Soviets then introduced Kim Il Sung, and he assumed control of the Korean Communist Party in North Korea. The Provisional People’s Committee was created in North Korea as a centralized power for northern Korea on February 8, 1946. Kim Il-Sung became the chairman.

The US military government in Tokyo brought Syngman Rhee from the US to Japan following the Japanese surrender on September 2, 1945. The military government in Tokyo brought him back to Korea in mid-October 1945. He assumed top political positions in Seoul, opposed a trusteeship, refused to join the US-Soviet Joint Commission, and refused to negotiate with the North.

Violent discontent prevailed, most notably in the South, which I will address later.

In June 1946, Rhee argued for an independent government in South Korea. After much wheeling and dealing, he became the first president of the Republic of Korea (ROK) on August 15, 1946. The North established the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea (DPRK) on September 8, 1946.

The division of Korea was complete.

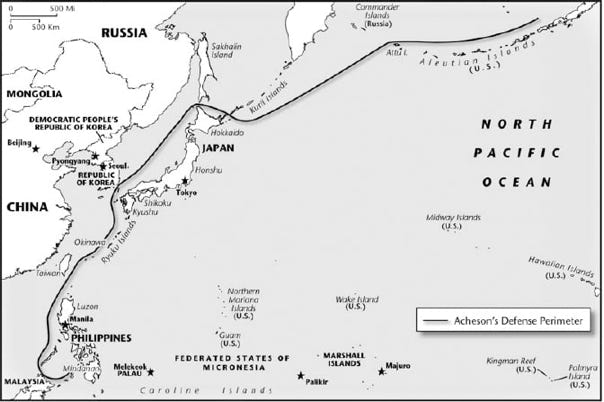

Korea outside the US defensive perimeter

James I. Matray, writing “Dean Acheson’s Press Club Speech Revisited,” noted Secretary of State Dean Acheson on January 12, 1950, said in a speech at the National Press Club that the US would provide for Japan’s defense and that an American “defensive perimeter runs along the Aleutians to Japan goes to the Ryukyus … The defensive perimeter runs from the Ryukyus to the Philippine Islands.”

That meant the ROK, established in 1948 and occupied by the US, was not in the US defensive perimeter. The Republic of China (ROC) on Formosa, led by US WWII ally Chiang Kai-Shek, was also outside the perimeter.

Matray wrote,

“Beyond Japan, the Ryukyus, and the Philippines, ‘it must be clear that no person can guarantee these areas against military attack.’”

Historians debate whether this ignited the Korean War. The statement did reflect Truman’s emphasis on economic aid instead of military power.

Miles Maochun Yu, writing for the Hoover Institution, opined that Acheson was issuing a warning meant for the USSR: do not conduct military actions in Asia, specifically Japan, the Ryukyus, and the Philippines.

A University of Pittsburg paper suggests the Acheson speech was also intended to warn ROK leader Syngman Rhee not to attack the DPRK. Note also that Formosa was omitted. Here again, Acheson warned the ROC leader, Chiang Kai-shek, not to pick a fight with communist China.

From the standpoint of the South Korean people, however, not only had they been occupied by the Chinese, Japanese, and now the Americans, but they had no American security guarantees either.

US forces withdraw from Korea

US forces arrived in Seoul on September 8, 1945. About 45,000 troops came to South Korea, mainly through the Inchon port. It was an occupation force. The American plan was to withdraw these forces within a few years.

In 1947, the JCS saw “little strategic interest in maintaining the present troops and bases in Korea.”

Recall that the US was quickly demobilizing its military forces. Military manpower was short. The JCS felt the 45,000 men in Korea “could well be used elsewhere.” The only concern was that the Soviets might establish a military base in North Korea from which they could attack Japan. The JCS was also worried about the rising disorder in Korea, disorder that might fall on American military forces to solve. I will discuss this point soon. But the JCS was correct in worrying about this.

JCS advocated that the US “should expand, equip, and train the Constabulary to protect South Korea against anything short of an ‘overt act of aggression.’” A constabulary is usually thought of as a police force. The JCS was emphatic that “the United States should not become so irrevocably involved in the Korean situation that any action taken by any faction in Korea or by any other power in Korea could be considered a casus belli for the US.”

The JCS opined that establishing the ROK on August 15, 1948, meant “the US military government in Korea came to an end.”

The plan was to begin withdrawing US military forces from the ROK on August 15, 1948, and complete the withdrawal by December 15. But that was delayed. The State Department felt it was too soon after the ROK was established. A new deadline of January 15, 1949, was set.

Communist-inspired rebellions shook the ROK and revolts within the constabulary. President Rhee asked for further delays.

Major General John B. Coulter, USA, commander of US Army Forces Korea, said he believed an invasion from North Korea was possible in the near future. The Department of State asked for a delay. On November 15, 1948, the Army instructed MacArthur to retain one reinforced regimental combat team of no more than 7,500 men.

National Security Council (NSC) Paper 8/2, approved by President Truman, stipulated that the US would withdraw all troops by June 29, 1949. However, General Omar Bradley, USA, chief of staff of the US Army, was concerned that a complete withdrawal would result in a North Korean invasion. The Army studied the issue. The JCS issued a memorandum that declared Korea was of “little strategic value to the United States.” It further said,

“Any commitment of US military force in Korea would be ill-advised, and that the introduction of an international army under UN sanction would be practicable only if the forces envisioned by Article 43 of the UN Charter were in existence.”

That’s a bit of a word salad. It’s important, so I will break it down.

“Commits all United Nations member states ‘to make available to the Security Council, on its call, armed forces, assistance, facilities, including rights of passage necessary for the purpose of maintaining international peace and security.’”

In other words, NSC 8/2, a commitment of US military forces in Korea, would be ill-advised unless a UN force existed. The last elements of US forces in Korea left on June 29, 1949. No UN force was there when the KPA invaded; therefore, there should be no commitment of US military force in Korea.

The US maintained an advisory mission called the US Military Advisory Group Korea (KMAG). General MacArthur relinquished all responsibility for Korea except for some minor KMAG support requirements.

Soviet forces were said to have withdrawn by the end of 1948. On June 27, 1949, the US Army told the State Department, “There is evidence that the Soviets left 2000 military advisory personnel and 1000 security personnel in North Korea.”

The Army urged the State Department “To encourage the Rhee Government to attempt the peaceful unification of Korea by direct negotiations with the North Korean regime.” The hope was this would forestall a North Korean invasion.

However, if there were an invasion, the Army recommended emergency evacuation of Americans, present the problem to the UN Security Council, initiate a police action with US and UN member nation forces to restore law and order, and reconstitute a US joint task force at the request of the ROK.

It is clear that the US military wanted to withdraw from the ROK but was nervous about doing so.

The CIA reported on February 28, 1949, “Consequences of US Troop Withdrawl from Korea in Spring, 1949.” It stated,

“Withdrawal of US forces from Korea in the spring 1949 would probably in time be followed by an invasion.”

The CIA opined,

“South Korean security forces … will not have achieved that capability (to resist such an invasion) by the spring 1949. It is unlikely that such strength will be achieved before January 1950. Assuming that Korean Communists would make aggressive use of the opportunity presented them, US troop withdrawal would probably result in a collapse of the US-supported Republic of Korea.”

The warning was clear. It was not heeded.

The Fury Inside South Korea

I mentioned earlier that when assessing US troop withdrawal from the ROK, the JCS was worried about the rising disorder in Korea, which might fall on American military forces to solve. That was a valid concern.

Tyler Lutz, Arcadia University, has written,

“(Korean) history was, for the most part, peaceful and stable until the late 19th century when increasing pressures from the West and the Japanese forced Korea to open up to the world. In 1910, Korea was formally annexed by Japan and remained under their control until the Allied victory in 1945. At that point, Korea’s history as a unified nation would come to an end, with both halves taking drastically different paths to independence.”

Therein lies the rub.

The Koreans thought the Japanese surrender had liberated them. They were wrong. Two new occupation forces, the Soviets and the Americans, divided the peninsula into two parts, which did not sit well with the Koreans.

Jeong-Sim Yang, Ewha Womans University, has written,

“Liberation at last. The day has come. The day–depicted by the poet Sim Hun in his poem: ‘The day when the Samgak Mountain shall stand up and dance; The day when the waters of the Han River shall churn and rise up’–has finally come. From the morning of August 16, 1945, youths, students and citizens started to flock towards Kyedong, Seoul, where the headquarters of the Committee for Preparation of Korean Independence was located. ‘A crowd of around 5,000 people gathered in the Whimoon Middle School sports field to listen to the speech of Yŏ Wun-Hyŏng and cheered the country’s independence. Yŏ Wun-Hyŏng, wearing a white suit and surrounded by the crowd, delivered a passionate speech. It was a moment when both legendary figures like the independence leader Yŏ as well as ordinary Koreans all expressed joy of being liberated and high expectations for a new society that would soon dawn.’

“However, the raptures of liberation did not last long. The militaries of the United

States and the Soviet Union advanced onto the Korean peninsula, and a shadow

began to cast over it.”

I’ll not address what was happening inside North Korea, mainly because we do not know. US Army History talks about North Korea,

“Behind a facade of native government the Russians were communizing North Korea without arousing the storms of critical protest that met the Americans in their efforts to democratize South Korea.

“Russian policy in North Korea was aimed at creating an indigenous government which would be a replica of the Russian political system and subservient to the Soviet Union. The ready-made strong Communist organization in North Korea as well as the area's nearness to Manchuria and USSR territory made the job easy for the Russians. They brought back to Korea thousands of Korean expatriates who had lived, studied, and become completely communized in the USSR. A few had held government or party posts in Moscow.”

Returning to Tyler Lutz, he summed up the DPRK this way,

“Its (North Korean) people have lived under the dictatorial rule of the world’s only dynastic communist regime, that of the Kim family.”

The situation in the ROK was entirely different. Syngman Rhee, its first leader, was no angel, but we know much more about the ROK’s evolution after WWII. Rhee had lived much of his adult life abroad. He received degrees from George Washington University and Princeton. After WWII, he returned to Korea and became the ROK president in 1948. He was an ardent supporter of Korean independence and unification. He was also a strident anti-communist. He was autocratic.

His autocratic style created enormous upheaval in the ROK, along with the US military presence and communist activism.

Maya Chu, writing “A pioneering figure with a marred legacy: Syngman Rhee at Princeton,” wrote,

“Rhee implemented laws that severely curtailed political dissent. He purged the National Assembly of members who opposed him and later had the leader of the opposition Progressive Party, Cho Bong Am, executed in 1959. He also controlled appointments of local officials, detained and tortured suspected communists, and violently quelled uprisings.”

Jeong-Sim Yang has passed on one more thought about South Korea,

“The joy of liberation and the yearning for a new world disappeared like a momentary dream, coming and going as quickly as thunder.”

US Army History wrote,

“In the fall of 1946, after Korean mobs overran several police stations and seized arms and ammunition, General Hodge declared martial law.”

Far more than that happened. Shin Bok-ryong, writing “The Origins of the Korean War, Kim Il-sung’s Intention to Begin the War,” points to three significant incidents in the ROK that created considerable turmoil:

The Daegu Incident of 1946

Koreans rose against the US Army Military Government in Korea (USAMGIK). It began in September 1946 in Pusan and spread throughout South Korea. The uprisings also called for better working conditions, wages, and the right to organize. On October 1, 1946, thousands congregated at the Daegu Station to protest against US governance. The protest became violent, and the police shot and killed a factory worker. The protests continued the next day. The Korean Communist Party sent in its rioters who broke into 22 police stations. The US sent in troops and declared martial law.

Military-history.fandom.com has written

“According to the conditions the United States Military Government responded in different ways, including mobilizing strikebreakers, the police, right-wing youth groups, sending in U.S. troops and tanks, and declaring martial law, and succeeded in putting down the uprising. The uprising resulted in killing of 38 policemen, 163 civil workers, and 73 civilians.”

Jeju Rebellions

Jeju is the largest island off the southern coast of Korea. The uprisings in Jeju extended from April 1948 through May 1949. They were nasty.

Jeong-Sim Yang has written,

“There were two main reasons behind the Jeju 4.3 Uprising.

“One was defensive in nature. The islanders were trying to defend themselves against the continuous suppression by the US military, right-wing groups and the police ever since the police opened fire at the Jeju people on March 1, 1947.

“The uprising also occurred as part of the political struggle to establish a unified government by opposing the election scheduled to take place only in southern Korea. The movement to protest the separate election scheduled for May 10, 1948 spread nationwide, and the one in Jeju is historically assessed to be the most well-organized.”

Jeong-Sim Yang has said,

“The official number of (of people who died) was well over 10,000. However, the Jeju 4·3 Incident Investigation Report estimated the actual number of deaths to be between 25,000 and 30,000, which was approximately one-tenth of the entire Jeju population.”

She continued,

“The reason why so many people died was because of the hardline suppression implemented by the punitive forces led by the US Army Military Government in Korea (USAMGIK) and the Syngman Rhee regime.”

The Hudson Institute has written,

“On April 3, 1948, on the Korean island of Jeju, communist guerrillas went on a rampage, killing police officers, election workers, and others; setting houses on fire; and terrorizing villagers, all to discourage them from voting in the upcoming May 10 elections that would establish the Republic of Korea (ROK). The insurgency—referred to as Jeju 4.3—triggered a government counterinsurgency, forcing the communists into the mountains where they would continue their guerrilla operations for nine more years.”

The communists took advantage of anti-American sentiments resulting from the US agreeing to divide the peninsula and opposition to the US military’s governance over the South. Some argue it was a democratic movement. Others say the instigators intended to unify the peninsula under communist rule.

My cursory reading indicates that Koreans had hoped for independence and self-rule in a united Korea. Instead, they received two new forces of occupation, one of which was the US military. The well-organized communists put that to good use and created enormous upheaval in South Korea by attacking the unjust conduct of USAMGIK. Many Koreans on the island viewed the USAMGIK as oppressors.

As is so often the case, a tripwire incident occurred where the horse of a mounted police officer trampled a young boy in a crowd of Koreans marching to an elementary school to celebrate the March 1 Independence Movement. The police officer involved ignored the injured boy, and people in the crowd rioted. The police were deployed from the mainland by the USAMGIK, and they fired on the crowd, killing six. All hell broke loose on April 3.

Military Insurrection in Yeosu-Suncheon

A violent protest broke out in Yeosu, a port city in southern Korea, against the Syngman Rhee government, a staunchly anti-communist government. Men in a military regiment in Yeosu refused to deploy to Jeju Island to suppress a rebellion there. It is said these men were sympathetic to the communists. Their refusal blossomed into a widespread revolt, such that the protesters attempted to set up their own Korean People’s Republic. US Army and US Army-led South Korean military troops were deployed to suppress the rebellion. Those killed numbered in the hundreds and possibly even the thousands. Syngman Rhee imposed martial law.

Shin Bok-ryong notes that Koreans have long been resisters. They had been under the yoke of iron-handed Japanese occupation for 35 years. Koreans defied them where they could. Now, they defied Syngman Rhee and the US military.

The American history with Korea was one of benign neglect. The US did not consider Korea to be important. However, given Soviet expansionism and the loss of China to the communists, the US was not about to leave the entire Korean peninsula to the Soviets. Koreans found themselves trapped in the vice of US-Soviet competition.

The peninsula's division occurred during a “state of chaos and disorder” as told by Shin Bok-ryong. K-Developedia said the Soviet and American occupations created “an identity crisis” among Koreans, which in turn drove ideological conflicts. Koreans also faced a leadership vacuum. The trusteeship issue “added to a state of confusion.”

Making matters worse, Korea suffered from political and economic problems. The Japanese had run virtually everything, and now they were gone. The net results were severe poverty and intense social conflict. Workers regularly and actively took to the streets in desperate attempts to secure their livelihoods. The USAMGIK, instead of accommodating the workers’ demands, reacted to these activities with increasing levels of violence and oppression.

The Association for Asian Studies has said,

“US military occupation of southern Korea began on September 8, 1945. With very little preparation, Washington redeployed the XXIV Corps under the command of Lieutenant General John R. Hodge from Okinawa to Korea. US occupation officials, ignorant of Korea’s history and culture, quickly had trouble maintaining order because almost all Koreans wanted immediate independence. It did not help that (the US) followed the Japanese model in establishing an authoritarian US military government.”

The North Invades: A Surprise?

North Korea invaded South Korea on June 25, 1950. It is commonplace to say this invasion came as a surprise. In retrospect, and with the benefit of hindsight, it is hard to fathom why the American political and military leadership was surprised.

The US had no combat forces in the ROK. Those who had been there in 1945 were unpopular and seen as oppressors, and they were withdrawn by June 29, 1949. The closest ground forces were in Japan, and they were not combat-ready.

The US excluded the ROK from its defensive perimeter. US military forces withdrew from South Korea in 1949. U.S. Army Forces in Korea (USAFIK) was deactivated by midnight on 30 June 1949.

The US trained and equipped a Korean constabulary to protect the ROK against anything short of overt aggression. The constabulary became the ROKA, reaching 65,000 by 194, but the US equipped it at 50,000. It was poorly trained.

South Korea was awash with Korean communists. One has to assume they knew the US had little strategic interest in Korea and instead focused on the USSR in Eastern Europe and Japan.

Kim Il-Sung and Syngman Rhee both wanted to unify the two Koreas under their flag at the expense of the other. Kim went to the Soviets multiple times for help, but reunification was not on the US agenda.

The Soviets closed off the DPRK. The State Department has said, “When North Korea invaded South Korea on June 25, 1950, the U.S. intelligence organizations had few resources or personnel dedicated to Korean matters.

Communist-inspired rebellions and revolts shook the ROK. Shin Bok-ryong contends,

“Military clashes on 38th Parallel were so frequent that the Americans in Korea did not believe it when they received the news of the invasion on June 25th (Noble 1975: 13). Most of the citizens in Seoul did not believe the news either (Kim 1993: 54), but many in the Korean Army were not surprised (Lee 2001:1).”

US Army History said,

“Two weeks after he had accepted the surrender of the Japanese south of the 38th Parallel in Seoul on 9 September 1945, General Hodge reported to General MacArthur in Tokyo, ‘Dissatisfaction with the division of the country grows.’”

During March 1950, there were rumors of an impending invasion of South Korea. During March 3-10, 1950, March, twenty-nine guerrilla attacks in South Korea and eighteen incidents along the Parallel occurred. Army History noted,

“Beginning in May 1950, incidents along the Parallel, and guerrilla activity in the interior, dropped off sharply. It was the lull preceding the storm.”

General MacArthur told the JCS his views on the possible effects of military withdrawal from the ROK. MacArthur’s response was predictably blunt,

“The threat of invasion possibly supported by Communist Armies from Manchuria will continue in foreseeable future. It should be recognized that in the event of any serious threat to the security of Korea, [U.S.] strategic and military considerations will force abandonment of any pretense of active [U.S.] military support."

CIA has commented, “(General) MacArthur was confident of his capabilities to reshape Japan, but he had little knowledge of Chinese Communist forces or military doctrine. He had a well-known disregard for the Chinese as soldiers.”

CIA reported in October 1948 “that a North Korean attack on the South is ‘possible’ as early as 1949, and cites reports of road improvements towards the border and troop movements there. It also notes, however, that Moscow is in control.”

CIA warned in 1949 that an invasion would follow the withdrawal of US forces. The Korean Liaison Office, a secret intelligence outfit in Seoul, in 1949 “was reporting that the Communist guerrillas represented a serious threat to the Republic of Korea (ROK). The office also noted that many of the guerrillas were originally from the South and thus were able to slip back into their villages when hiding from local security forces.”

CIA reported in the spring of 1950,

“North Korea’s preparations for war had become readily recognizable. Monthly CIA reports describe the military buildup of DPRK forces but also discount the possibility of an actual invasion … Throughout June (1950), intelligence reports from South Korea and the CIA provide clear descriptions of DPRK preparations for war … On 20 June 1950, the CIA published a report, based primarily on human assets, concluding that the DPRK had the capability to invade the South at any time.”

Army History commented,

“Elements of four ROK divisions and a regiment (were) stationed along the south side of the Parallel in their accustomed defensive border positions. They had no knowledge of the impending attack although they had made many predictions in the past that there would be one. As recently as 12 June the U.N. Commission in Korea had questioned officers of General Roberts' KMAG staff concerning warnings the ROK Army had given of an imminent attack. A United States intelligence agency on 19 June had information pointing to North Korean preparation for an offensive, but it was not used for an estimate of the situation. The American officers did not think an attack was imminent. If one did come, they expected the South Koreans to repel it. The South Koreans themselves did not share this optimism.

“Even though four (ROKA) divisions and one regiment were stationed near the border, only one regiment of each division and one battalion of the separate regiment were actually in the defensive positions at the Parallel. The remainder of these organizations were in reserve positions ten to thirty miles below the Parallel. Accordingly, the onslaught of the North Korea People's Army struck a surprised garrison in thinly held defensive positions.”

The JCS position was that any commitment of US military force in Korea would be ill-advised. Regarding the American zone of Korea, Secretary Acheson hoped that extending economic aid to the ROK would help it develop into a peaceful country. But he encountered stiff congressional resistance to providing such aid.

Army History has said further,

“The North Korean attack surprised official Washington. Maj. Gen. L. L. Lemnitzer in a memorandum to the Secretary of Defense on 29 June gave what is undoubtedly an accurate statement of the climate of opinion prevailing in Washington in informed circles at the time of the attack. He said it had been known for many months that the North Korean forces possessed the capability of attacking South Korea; that similar capabilities existed in practically every other country bordering the USSR; but that he knew of no intelligence agency that had centered attention on Korea as a point of imminent attack. [4] The surprise in Washington on Sunday, 25 June 1950, according to some observers, resembled that of another, earlier Sunday-Pearl Harbor, 7 December 1941.”

James I. Matray, “Dean Acheson’s Press Club Speech Revisited,” highlighted an accusation made by Ohio Senator Robert A. Taft where Taft accused Truman and Acheson “of pursuing a ‘bungling and inconsistent foreign policy’ that had provided ‘basic encouragement to the North Korean aggression.’”

P.K. Rose, writing CIA “Two Strategic Intelligence Mistakes in Korea, 1950, Perceptions and Reality,” published in 2001, said,

“The United States was caught by surprise because, within political and military leadership circles in Washington, the perception existed that only the Soviets could order an invasion by a ‘client state’ and that such an act would be a prelude to a world war. Washington was confident that the Soviets were not ready to take such a step and, therefore, that no invasion would occur.”

What do you think?

Click to zoom graphic-photo