DUTY, HONOR, COURAGE, RESILIANCE

Talking Proud: Service & Sacrifice

Earthquake McGoon: Aviator

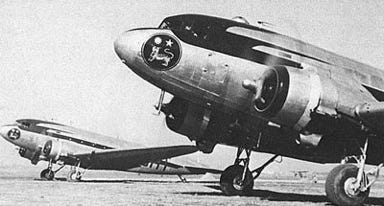

In May 2007, the US Joint POW/MIA Accounting Command (JPAC) in Hawaii positively identified the recovered remains of James B. McGovern, Jr. in Laos. Piloting a C-119 "Flying Boxcar" cargo aircraft for the CIA in support of the besieged French garrison at Dien Bien Phu on May 6, 1954, his aircraft was struck by ground fire. McGovern crashed into a hillside in Laos, about one-half mile short of an old abandoned runway.

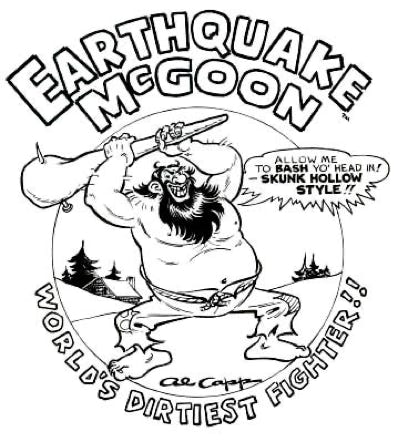

James McGovern is famously known as “Earthquake McGoon.”

Wayne Johnson delivered the eulogy for McGovern and described the nicknaming process this way,

"A recent news article reported that he was named Earthquake McGoon by a Chinese saloon keeper. That reporter didn't have his facts straight. He was actually named that by Phil Dickey, the armament officer in our squadron, the 118th Tactical Reconnaissance Squadron. Dickey loved the comic strip and would draw characters from it. Since Jim looked a bit like Al Capp's Li'l Abner comic strip character and made a try at making moonshine, the nickname fit him well.

“But McGovern was more than a comic strip character … He was a superb fighter pilot.”

Earthquake’s story is best told in two sections: US Army Air Corps (AAC) fighter pilot in China and CIA Air America pilot in the French Indochina War.

Fighter Pilot: China

James Bernard McGovern, Jr. was born in Elizabeth, New Jersey, on February 4, 1922. He graduated from Thomas Jefferson High School, trained as an aircraft maintenance technician at Casey Jones School of Aviation, and worked at Wright Aircraft Engineering Co. in Patterson, NJ. His life-long ambition was to be a pilot. As a young boy, he watched and built model airplanes. He enlisted in the aviation cadet program in early 1942, at the beginning of WWII.

McGovern completed all his flight and Army training in the US and was commissioned a second lieutenant in the Army Air Force (AAF).

Following his training in the US, 2nd Lt. McGovern was sent to the WWII China-Burma-India (CBI) theater, arriving in India in the fall of 1944. Before going to their operational unit, it was customary for these pilots to get some flying and familiarization training time at Landi Field, Karachi, India. Landi hosted the CBI Air Forces Training Command and the CBI Fighter Replacement Training Unit.

After training in Karachi, Lt. McGovern was assigned to AAF’s 118th Tactical Reconnaissance Squadron (TRS), Liuchow, China, arriving there in early November 1944. It was attached to the 23rd FG and, with its other fighter squadrons, began flying P-40 combat operations in China.

Chungkung was used as the headquarters and support area. Japanese military forces were moving into southwest China toward French Indochina and Hong Kong. The 118th TRS was at Liuchow, China. The Japanese began bombing the Liuchow Air Base (AB). In early November 1944, the 118th had to leave.

Toward the end of the squadron's stay at Liuchow, there was a major pilot rotation. To some old hands, the pilots rotating out were known as "the first group." The first group flew the P-40. The second group came, and with them came the P-51 B/C Mustang, which had greater range and far better performance than the P-40.

The 118th was flying the reconnaissance version of the P-51 Mustang, known as the F-6C. While at Liuchow, the squadron men decided to take the name “Blue Lightning Squadron.” They tried to get some blue paint for nose art but could not find any. Black paint was available, so they renamed their “Black Lightning Squadron.”

Wayne Johnson, a squadron mate, has estimated that McGovern was assigned the nickname “Earthquake McGoon” in late December 1944 or early January 1945. Johnson has said,

“(Phil) Dickey loved the (Li’l Abner) comic strip and would draw characters from it. Since Jim (McGovern) looked a bit like Al Capp's Li'l Abner comic strip character and made a try at making moonshine, the nickname fit him well. But McGovern was more than a comic strip character."

The Li’l Abner comic strip character became known in the 1930s. The nickname “Earthquake McGoon” stuck on McGovern.

Joe Grant shared a tent with McGovern and called him “Typhoon McGoon.”

Back to the war in the CBI. The Japanese were attacking the airfield at Liuchow. The 118th was ordered to hop over the enemy and fly to Suichwan behind enemy lines, a bold move. The squadron history says:

"Basing at Suichwan put this squadron in one of the most unique positions in modern warfare. Staging offensive attacks against the enemy anywhere from 60 to 200 miles behind his lines brought in a new element of surprise."

The 118th TRS arrived at Suichwan on November 14, 1944, and conducted an intense air campaign against the Japanese supply routes from the east coast. The Japanese had no choice but to turn their attention to the East to drive the Allies out of their bases. December and January’s fighter sweeps against Hong Kong and Shanghai were especially effective for the 118th.

On January 20, 1945, the Suichwan-based 118th tasked 16 P-51s, all flown by its lieutenants, 2nd Lt McGovern included, to strafe airfields in the Shanghai area. They flew directly to Wuhing and then to the target at 10,000 ft. Ceilings were unlimited, and visibility was 1-5 miles in haze. They proceeded to the north and then cut eastward to the Shanghai area.

There was quite a bit of air-to-air action. McGovern, flying a P-51C, caught a Nakajima Ki-43 Oscar at 8,000 ft from astern, blew off a good burst, and the Oscar immediately burned. McGovern observed the pilot bail out. McGovern got one confirmed kill. McGovern then approached another Oscar, again from astern, fired off a long burst, and the Oscar blew up. McGovern also observed this pilot bail-out—a second confirmed aerial kill for McGovern.

The 118th encountered heavy and accurate anti-aircraft (AA) fire. The pilots noted it was a different kind of AA, including about 10 phosphorous explosions at altitudes ranging from 400 to 1500 ft. The Japanese managed to get 12 to 15 fighters into the air, but the Shanghai warning system appeared ineffective, as these fighters were climbing out when the 118th arrived. The enemy pilots were not ready to fight.

On their way home, McGovern caught a train locomotive at Hangchow RR station. He fired into it and probably destroyed it.

Thirteen pilots and their aircraft engaged in the attacks returned to base safely. Two were left missing.

Two days later, the squadron left the field because of Japanese advances on the ground toward it. The squadron moved to Chengkung. At this point, the Japanese were consolidating their hold on southeastern China, taking control of the Canton-Henyang railroad in February 1945.

The squadron moved to Laohwangping in April 1945. This base's task was to stop the Japanese advance against Chihkiang, which, among other things, hosted 14th AAF fighters and was a forward base. This map shows an approximation of the locations of Laohwangping and Chihkiang. The most notable point is that the Allies had been forced to leave the bases farther to the east, and now the Japanese were also trying to chase them out of airfields to the west.

USAAF transport aircraft brought the Chinese New Sixth Army equipment, supplies, ammunition, and everything they needed from rear bases. The aircraft landed at Chikkiang, offloaded and refueled at virtually the same time, and departed to get back to pick up more Chinese soldiers and bring them back. These Chinese forces formed a reserve, enabling the holding troops to push forward against the Japanese. In the meantime, fighter aircraft did what they could to beat back and slow down the Japanese advance. As a result of this coordinated US-Chinese effort, the Japanese attack failed, and they fell back. Furthermore, the Chinese moved into and took Nanning to the south, about 330 miles west of Canton, forcing the Japanese out. Together, these were substantial Allied victories.

Not many people realize that the Japanese invested a great deal in their operations in China. Most of their combat forces outside the home islands were assigned to the CBI, among her finest front-line units. Their problem in China was now made more difficult as the result of major US victories in the Pacific island-hopping campaign that would enable daily B-29 bombing of the home islands from the Marianas in the Pacific. The Allies were advancing toward the Home Islands, and the Japanese feared they might invade along China's coastline. They expected the Allies to invade the Home Islands themselves. One result was Japan had to begin withdrawing forces from China for use elsewhere.

The air war was essentially finished in China by July 1945. The emperor agreed to an unconditional surrender in August 1945, and the official surrender occurred in September.

The 118th helped oversee the Japanese withdrawal and slowly disbanded. It was officially deactivated in October, and most pilots were transferred to other units within the 23rd FG. McGovern was briefly assigned to the 75th FS. The 118th Squadron was then returned to the Connecticut National Guard.

Many accounts of McGovern's time in the CBI War say he had four aerial and five ground kills, but that is not true.

Arthur Wyllie's book WWII Victories of the Army Air Force (AAF) is a detailed and well-researched account of the AAF's actions during WWII. Wyllie lists McGovern as having achieved two aerial victories against the Japanese while flying with the 118th TRS.

One of his flying mates, Wayne "Whitey" Johnson, told me McGovern had two aerial and two ground kills.

This photo, which I understand to have been released by the McGovern family, is said to show Captain McGovern posing on the wing of his fighter aircraft at an unknown location. Note there are four Japanese flags on the fuselage, which might lead some to believe he had four aerial victories. In talking with Wayne "Whitey" Johnson, I learned that the two national flags of Japan, the rising sun on a plain white background, reflected aerial victories. The other flags with "sunrays" extending outward are the Japanese battle flag and reflected ground victories, i.e., aircraft on the ground destroyed. Johnson confirmed that McGovern had two aerial and two ground victories.

This is a group photo of 118th TRS "Red Flight" officers. Our man is third from the right in the back row. Bob Bourlier provided this photo and others.

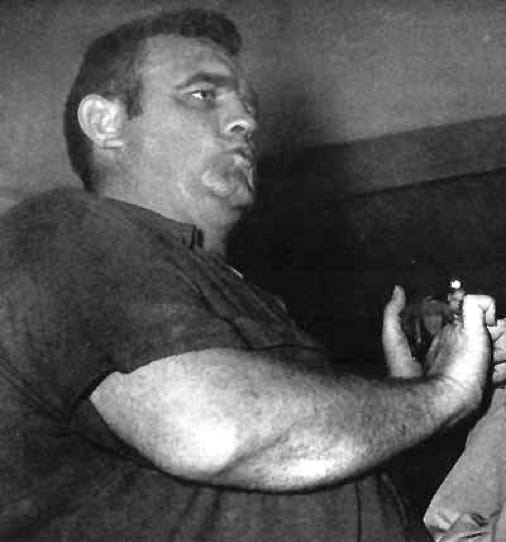

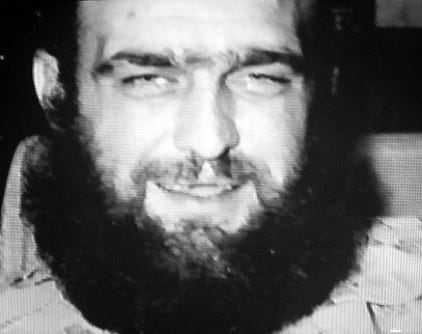

For his part, like Earthquake McGoon, McGovern was a big fellow, though he is not the tallest guy in the photo. That said, he was a big guy and carried a bit of a pot belly while in China. Wayne Johnson described him this way:

"McGovern's unshapely size, black bushy eyebrows, black beard (even after a fresh shave), his fondness for Jing Bao Juice, and his attempts to make his own moonshine, made him a natural as 'Earthquake McGoon.’ “

"Whitey" Johnson made it a point to say this about McGovern,

"McGovern was more than a comic strip character. He was a superb fighter pilot. He was the type of pilot that became part of the airplane. A careful pilot and one that one felt safe to fly with."

When I talked with Johnson, he repeated that everyone in the squadron considered him a good pilot. Johnson had written,

"As his girth grew, his crew chief would almost pry him into the cockpit of his P-51 Mustang. But once in the pilot's seat, he became part of the machine. McGoon was a natural-born fighter pilot. He was the pilot you liked to have along on a mission. Careful but tenacious."

Wayne Johnson recalled one more story. McGovern learned that a radio operator was stranded at a remote base, and the enemy was nearby. McGovern volunteered to fly in some explosives to blow up the equipment and brought some maps to show the radio operator some escape routes. However, McGovern flew to the site, landed, and decided to get the troop home in his P-51. McGovern climbed into his Mustang, left his parachute behind to make more room in the cockpit, gave the guy his helmet and goggles, put the radio op on his lap, and took off with the canopy left open and the radio operator's head above the canopy. McGovern landed and said this to the trooper,

"Better'n walking, wasn't it, son?"

McGovern’s flying days were not over.

CIA C-118 pilot: China

General Chennault was relieved of command of the 14th AAF in August 1945 and retired to Louisiana. He had become close to China’s Generalissimo Chiang Kai-shek and wanted to help in his war against communist Mao Zedong.

Along with attorney Whiting Willauer, Chennault established a Chinese national airline mainly to serve China’s transport needs.

The new China Airlines was officially called the China National Relief and Rehabilitation Transport Company. However, that name was too long and shortened to Civil Air Transport or CAT. Do not confuse this with CAT, Inc., which was a CIA company known as Air America. I will address this a bit later.

In any event, CAT, a Chinese company, was officially established as a commercial airline in Shanghai on October 25, 1946.

Chennault recruited from among those American fliers who served in China, mainly from the troop carrier squadrons.

The 23rd FG returned to the US and was inactivated. At the war's end, McGovern transferred to a troop carrier squadron in Beijing. He was discharged in 1947, and Chennault successfully recruited him to join the CAT.

There were plenty of "surplus" aircraft left in China. Chennault bought fifteen C-46s and four C-47s. By the end of 1948, CAT was flying many missions for the Chinese Nationalist government. It became deeply involved in the Chinese civil war.

On one flight, McGovern was forced to land his CAT aircraft in China and was captured. He was freed six months later. Legend has it that his guards were tired of how much he ate and his sense of humor. This photo shows him shortly after his release. His colleagues in CAT say he became a much more serious pilot after his capture and very anti-communist.

The Chinese nationalist government could not withstand the weight of the communist movement. In 1949, the communists took over and established the People's Republic of China (PRC). Chiang Kai-shek's government then moved to the island of Formosa to run what was left of the Republic of China (ROC), today known as Taiwan.

Chennault had to move CAT to Hong Kong but faced legal problems with the British concerning ownership of his aircraft. Those he did not lose to the PRC through this legal battle soon fell into disrepair. Chennault moved the company to Formosa in 1950.

Many in the US were startled to learn that communists had taken over China. Accusations were made that President Truman lost China. It was a tough time for the US, made more tough when North Korea invaded South Korea, and the US found itself at war.

The CIA wanted the US government to buy Civil Air Transport. The powers in Washington rejected that idea. As a result, the CIA developed a plan to buy the company indirectly. It presented its plan to the National Security Council (NSC), which approved it.

As a result, CAT, Inc. was organized to buy part of Civil Air Transport. All of the pilots were transferred to CAT, Inc. In turn, CAT, Inc. was set up as a wholly owned Chinese company. It owned all the aircraft and maintenance facilities. That company was named Asiatic Aeronautical Co., Ltd. Its name changed to Air Asia Ltd. in 1959. CIA initially operated this company.

The corporate-government structural actions for all this thereafter are too confusing to summarize here. The point is that CAT, Inc. and Air America were the same. Indeed, on March 26, 1959, CAT Inc.’s name was changed to Air America.

Chennault turned to the CIA. The CIA saw the advantages of an alliance with a transport company in the Far East and started advancing money. A central player in this was Paul Helliwell, shown here, courtesy of the Spartacus School in the UK. Helliwell, a lawyer, was a former Office of Strategic Services (OSS) officer, the OSS being the predecessor to the CIA. By this time, he was now a CIA officer.

An intelligence element of the War Department sent Helliwell to Formosa in 1950. His task was to help Chiang Kai-shek prepare to invade China. As part of this effort, he supported Chennault's endeavors to set up the CAT to conduct covert flight operations for the CIA.

CAT-Air America grew by leaps and bounds. I have seen different reasons reported regarding why Chennault went to the CIA. One set says the airline was short of funds, given the Nationalist loss to the Communists. Another is that he hated the Chinese communists and wanted to do what he could to thwart the spread of communism. I suspect there are elements of truth to both versions.

Without going too deeply into this fascinating history, the OSS sent agents to China during WWII—while there, they befriended a Vietnamese communist guerrilla, Ho Chi Minh. Ho became a strong ally of the US in the fight against the Japanese and the French Vichy government running Indochina. Indeed, Ho's Viet Minh army helped down US pilots in Indochina.

It was well known in Washington circles that Ho's main objective was to terminate the Japanese presence in Indochina and then terminate French colonial lordship over Indochina, specifically Vietnam. Many in senior levels of the US government, FDR included, favored Ho over the French. They knew his troops were fierce fighters against the Japanese and Vichy. US relations with France were strained because of the Vichy government and French attitudes in the European Theater of WWII, and it was evident that Ho was extremely popular with his people back home and would ultimately lead the country. Furthermore, FDR opposed French and British colonization.

US policymakers, most notably President Truman, faced a dilemma following WWII. On the one hand, they knew Ho Chi Minh was extremely popular among Vietnamese. On the other hand, they saw France as an ally. Ho was a communist, and the Cold War against the communists was in its infancy. The US abandoned Ho and helped the French.

In 1945, President Truman approved French resumption of colonial authority over Indochina. The Japanese had thrown the French out in 1945. The Japanese surrendered in September 1945. Ho declared independence. In 1946, the French tried to force their way back, and the French-Indochina War began.

The French were sorely short of transport aircraft and took every avenue available to get help from the US. Both the CIA and the USAF provided this support to them.

Jim McGovern started flying C-47 flights for Air America out of Saigon in early 1951. I understand he used a single C-47 in Saigon to do this job. His mission was to fly supplies within Vietnam for the US Special Technical and Economic Mission, which was supposed to be a mission to effect agrarian reform. However, as the days and weeks passed, he found himself flying more and more in support of French military forces.

His were civilian flights run by the CIA. However, the newly formed US Air Force (USAF) was also involved in the transport business and supported Air America and French flight operations.

In November 1951, the US supplied the French with 20 C-27s, which would grow to 116 by the war's end in 1954. USAF crews delivered the aircraft, usually from Clark AB, Philippines, to Nha Trang, Vietnam. These were for tactical airlifts. However, France lacked pilots and maintenance crews.

Since the French were short on pilots, the US turned to Air America, which, by 1952, was owned by the CIA lock, stock, and barrel. Air America pilots began flying a heavy schedule of transport missions for the French. These were combat missions flown by American civilians in every sense of the word. They routinely flew into combat zones, dropped supplies to the French, and dropped French paratroopers. They took their share of hostile fire.

The French lacked the strategic airlift to get their troops from France to Vietnam. In April 1952, the USAF's 62nd Troop Carrier Wing (TCW) flew French forces from France to Indochina aboard C-124 Globemaster IIs.

Since the French could not maintain their tactical transports, they asked for help from the US. President Truman sent the first US military forces to Vietnam, a group of 30 Air Force maintenance troops. The aircraft were American-owned and bore French markings but retained USAF serial numbers.

The C-47s proved insufficient in number, so the French asked the US for C-119s, at the time, the USAF's workhorse. The US was fighting in Korea, but by late 1952-1953, the ground war in Korea was in a stalemate, and C-119s became available.

After the usual political dancing, President Eisenhower approved sending C-119s to Indochina, but they would have to be flown by US-trained French pilots and Air America pilots, not USAF crews. The Air America pilots could transition to the C-119 far more quickly than French pilots could be trained, so Air America bore most of the load. The USAF 483rd Troop Carrier Group (TCG), formed at Ashiya AB, Japan, on January 1, 1953, trained French pilots and mechanics on temporary duty in Hanoi as part of "Operation Swivel Chair."

Allen Cates, a former Air America pilot and author of Honor Denied: The Truth about Air America and the CIA, has provided some advice that applies here. He wrote,

“The CIA was involved but so was the AF. For this operation Air America pilots interacted more with the USAF than they did with the CIA. I have a copy of one of the contracts. It clearly states the French Republic controlled the assets. The planes were loaded with ammo by Air Force personnel and fueled and maintained by Air Force personnel.”

From 1953 until the French defeat at Dien Bien Phu in May 1954, there was tremendous activity between Washington and Paris regarding what the US should do to help. This period merits further study. Believe it or not, some wanted to employ B-29 heavy bombers against the Viet Minh, including a nuclear attack.

I’ll stick to events relevant to the Earthquake. These events provide a good idea of what McGovern got into regarding the French-Indochina War.

In April 1953, a group of Air America pilots went to the Philippines, checked out, and delivered the first six C-119s to Gia Lam Airfield outside Hanoi on May 4, 1953. This was called "Operation Squaw." Some 18 USAF mechanics were sent along with them. The US agreed to send the C-119s mainly because the French said they needed to airdrop heavy equipment, and the C-47s could not handle that. USAF C-124 aircraft were used to medevac wounded French soldiers from Vietnam to Japan, so they were not available for airdrops.

It is worth noting that the USAF 315th Air Division commanders did not like these operations. There was quibbling between the US and French about the C-119s, so they were sent back to the Philippines, where they could be called on to return to Vietnam as required. They left on or after July 16, 1953.

The CIA has said that the aircraft and crews were withdrawn because of a "waning of the Viet Minh offensive." In retrospect, that does not ring true. The Viet Minh offensive was about to blow the French out of Vietnam.

Later on, in 1953, the French command decided to set up an air base deep in Vietnam, close to Laos, to enable improved operations against the Viet Minh operating from Laos. This base was in a valley on a fairly large plain, surrounded by mountains, and was known as Dien Bien Phu.

More than 60 C-47s dropped two paratroop battalions into the area in November 1953 to get things started. Later in the day, reinforcements were also dropped.

The C-119s were initially needed to bring in the heavy equipment to build the base and airstrip. The USAF's 483rd Troop Carrier Group (TCG) out of Japan made about 22 C-119s available at their base in Japan for duty in Vietnam as needed. Twenty-four Air America pilots flew 12 of these, all C-119C models. I understand from the French Embassy in Washington that the total number of Air America pilots who flew over Dien Bien Phu was 37. This was called "Operation Squaw II."

The C-7 Caribou Association's "History of the 483rd" talks to Project "Iron Age," wherein USAF crews would fly a few C-119s into Cat Bi, Vietnam, for loan periods of about five days. The Caribous wrote this:

"483rd Wing Operation Plan 4-53 sent aircraft to Air America Bi, Vietnam for loan periods of around five days. USAF crews were to ferry the planes to Indochina and return them to Japan as soon as specified airdrops were completed. General Macarty was afraid the French would misuse the planes for 'champagne and ice runs' and this short-term plan was designed to prevent such misuse. The planes would have French markings but the 483rd personnel would wear their own uniforms while performing maintenance and technical supply functions."

A USAF maintenance detachment of about 121 men was kept at Cat Bi to help keep the 119s flying. The detachment served on temporary duty for about 60 days. They often had to fly aboard a 483rd aircraft to various bases in Laos to repair damaged C-119s forced to land there and return them to base.

It is worth noting that three enlisted USAF and two US Army parachute riggers were captured at the French base at Tourane, later known as Danang, and released after six weeks of captivity.

C-119s then started bringing in the heavy-duty stuff, including barrels filled with napalm, in effect making the C-119 a bomber, a tactic employed during the Korean War. On occasion, some USAF people were on some of these combat missions against the prevailing rules.

Once the French got established, the Viet Minh set up shop, zeroing in on targets at the Dien Bien Phu base from the surrounding hills. The C-47s managed to land, but the C-119s usually had to drop their loads from the air. After a while, Viet Minh artillery was so plentiful and persistent that all equipment and supplies had to be air-dropped. The Viet Minh’s capabilities in the area became so strong that the air transports came under heavy fire on approach and departure. French pilots could not handle getting in and out, so the Air America guys took over most of the flights.

Sam McGowan wrote this about the Earthquake:

"The Air America pilots took a special interest in the Frenchmen on the ground and often included special goodies they had bought with their own money with the supplies they dropped. When 'Earthquake' McGovern heard that the colonel in charge of the base had been promoted, he went out and bought the proper insignia, and attached it to a bottle of champagne, and dropped it into the camp. McGovern also took advantage of the flights to get rid of his unpaid bills - he ripped them up and tossed the pieces out the window of his Dollar Nineteen as he came into 'The Slot' leading into the valley!"

Air America aircraft and pilots were hit on more than one occasion.

I need to pause for a moment to introduce you to Wallace Buford.

Wallace Buford served as an Air America, WWII and Korean War pilot, first with the Army Air Corps and then with the newly formed US Air Force. While on active duty, Buford received the Distinguished Flying Cross twice and the Purple Heart.

McGowan described an Air America flight in which Buford's aircraft took some fire,

"Every mission over Dien Bien Phu was greeted by flak...On one of the drops, the Air America chief pilot, Paul Holden, was hit in the arm when his C-119 penetrated a wall of flak over the valley.

"Holden ripped off his shirt and applied a tourniquet to his half-severed arm while the co-pilot, Wallace Buford, flew the airplane back to Cat Bi. When they landed, McGovern inspected the flak-riddled cockpit and remarked to Buford that 'Somebody must have been carrying a magnet.'"

McGowan added:

"A week later McGovern’s airplane was hit as he was pulling up after a drop. The C-119 pitched off onto one wing in the beginnings of a spin. As he was adding rudder to bring the huge transport out of the spin before it hit the ground, McGovern committed over his radio that 'I seem to be having a little trouble holding this thing.' On the way to Cat Bi, he commented, 'Now I know what it’s like to ride a kangaroo.' When he landed, Buford came up and asked, 'Did you borrow my magnet?'”

They may have been carrying a magnet on May 6, 1954. McGowan has written this:

"On May 6, 1954, McGovern and his co-pilot Wallace Buford flew in formation with five other C-119s, McGovern flying number two, aboard aircraft serial number 149.”

This was French Lt. Arlaux's first combat mission and the first time he met McGovern. He reported:

"James McGovern, the pilot, creates an unforgettable impression on me right from the first meeting. On the airstrip of Cat Bi, his figure is quite heavy. He wears carpet-slippers and a very loose Hawaiian-style shirt, colorful and flowery. He looks at me with a hearty, lovely smile and puts his arm around my shoulder. I am totally under the spell. I was not familiar with this sort of attitude, and discovered a new dimension in human relationships: friendship and informality, sincere kindness, cheerfulness and an unabated optimism in spite of the hardships and gravity of the situation. With McGovern nothing is to be worried about."

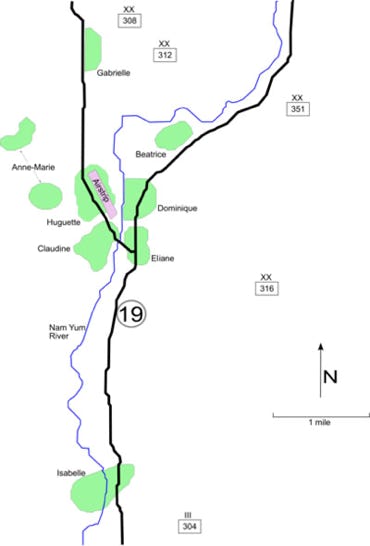

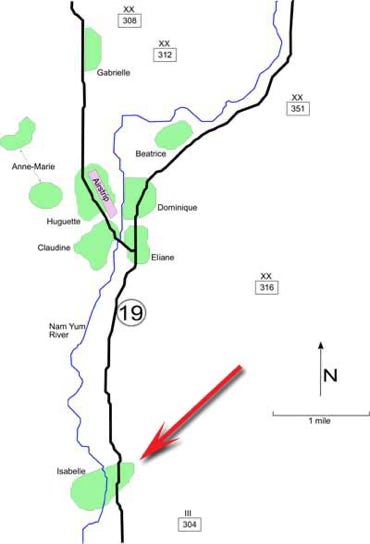

McGovern’s target was Camp Isabelle, 5km south of the main base at Dien Bien Phu. They were to deliver about 12,000 lbs of supplies. Isabelle was in terrible shape. A massive artillery attack on March 30 enabled the Viet Minh to dig in and conduct trench warfare. By the end of April, the camp was out of supplies, surrounded, with no way out. As history would have it, McGovern's final mission would be on the last evening before the fall of Dien Bien Phu to the Viet Minh Communists.

Talking about the load of supplies they carried, Arlaux said,

"Each pallet has been carefully conveyed into the rear of the plane, bundles are hooked to a ring fixed on a line, strapped with parachutes, ready to be released by a mechanical device when altitude and precise goal is properly assessed. This is difficult in the present situation, because the massive Viet Minh presence is everywhere, fighting openly or from secret hideouts, shelling from trenches, caves and hill-posted encampments taken from the French. Most of the parachuted packets missed the goal and fall into the enemy lines or get lost."

The website “Check-Six.com” described this mission, saying McGovern’s C-119 launched from Haiphong’s Cat Bi Airport on May 6, 1954, with five other C-119s,

“McGovern's plane was carrying a parachute-rigged Howitzer artillery piece to aid the French soldiers at Camp Isabelle – the southernmost firebase of Dien Bien Phu.

“The first aircraft in the flight, flown by Steve Kusak, safely dropped its load on Isabelle. But as McGovern approached the drop zone, however, his aircraft was hit twice by 37mm anti-aircraft fire, in both the left engine and stabilizer. ‘I've got a direct hit,’ other pilots heard McGovern say.

“Immediately, the French crew of ‘kickers’ in the aircraft's rear, named Jean Arlaux (on his first combat mission), Bataille, Moussa (a Malaysian), and Rescouriou, dropped their cargo, as McGovern shut down the burning engine, and climbed over the mountains surrounding the fort.

“With one engine afire, McGoon nursed the aircraft another 75 miles southward, into Laos. Approaching 4,000-foot mountains, he radioed fellow C-119 pilot Steve Kusak for help in finding level ground. ‘Turn right,’ said Kusak, who was directing McGovern towards an airstrip near the Nam Ma River.

“Forty minutes after being hit, McGovern made his last radio transmission, ‘Looks like this is it, son.’ His crippled C-119 Flying Boxcar cartwheeled into a Laos hillside near the Sang Ma river in Houaphan Province. (Actual photo of McGovern’s C-119 after impacting the ground in Laos).

“The crash killed McGovern, Buford, and two of the French crewmen instantly. But two of the cargo handlers, French Lieutenant Jean Arlaux and Private Moussa, were thrown clear and survived, but were captured by the Vietminh. Moussa died a few days later of his injuries.”

Felix Smith, a retired CAT pilot, “recalled McGovern as being ‘a real big-hearted guy,’ but not the ‘wild man’ as the press widely reported. ‘He was a bon vivant, happy-go-lucky. He loved kids, and he was the guy who in a tense situation would come out with some joke.’"

The remains of McGovern were found in 2002 by laboratory experts at the U.S. military's Joint POW/MIA Accounting Command. He was interred in Arlington National Cemetery on May 24, 2007, in Section 8-M4, Row 11, Site 6.

Click to zoom graphic-photo