DUTY, HONOR, COURAGE, RESILIANCE

Talking Proud: Service & Sacrifice

U-223 sank the Dorchester

While driving on one of my “get lost” rides, this time through Clark County, Wisconsin, I went into the village of Dorchester, population 875 or so. Coming upon a small park, I could see an American flag flying from atop what, from a distance, appeared to be a carefully arranged pile of stones. After getting closer, it became apparent that this memorial looked like a naval memorial. Part of a black anchor lay on the ground, a plaque was inset into the stone, and more of the anchor mechanism was above the plaque.

What would a naval memorial be doing in the middle of the state? I was about to learn a little-known piece of history.

This was a memorial to the US Army Transport, USAT, Dorchester. The Dorchester had once been a luxury liner, but it was no longer very luxurious and, in any event, stripped of all non-critical amenities.

During World War II, on January 23, 1943, the Dorchester left New York, packed to the limit with some 597 soldiers and 171 civilians bound for war, Merchant Marine Captain (Master) Hans Danielsen in command.

The Dorchester joined convoy SG-19 at St. John's, Newfoundland. “SG” is an Allied convoy code used from 1942 to 1945 to describe the route: Sydney (Nova Scotia) to Greenland.

SG-19 left St. John's bound for the Army Command Base at Narsarsuaq in southern Greenland. SG-19 consisted of six ships: Dorchester, two merchant ships leased by the United States from the Norwegian government-in-exile, D/S (Diesel Ship) Lutz, and D/S Biscaya. They were escorted by three small United States Coast Guard (USCG) cutters: Comanche (WPG-76), Escanaba (WPG-77) (both 165 feet), and Tampa (WPG-48) (240 feet).

Chuck Hill, a 1969 graduate of the Coast Guard Academy and a USCG retiree, runs a blog about Coast Guard matters. He published a story, “Convoy SG-19 and the Sinking of USAT Dorchester–When Things Went Terribly Wrong.” He opined that three USCG cutters were an insufficient escort for this voyage. He said the Tampa was old and not very fast. The other two cutters were even slower, barely able to keep pace with the ships being escorted.

This was Dorchester’s fifth North Atlantic trip. The Army History website said four German U-boats were stationed along the Dorchester’s route. The Dorchester sailed in the center of the three merchant ships, the Comanche and Escanaba sailed on each flank, and Tampa was the lead.

Karen Evans posted a story titled “No Greater Glory, 3 February 1943.” The story said one of the U-boats in the region was U-223 on her maiden voyage. Evans provides a good resume of four Army chaplains who were aboard.

Chuck Hill wrote that U-223 approached the convoy on its starboard (right) side, probably between Tampa and Escanaba. He said Escanaba, “even at this late date, still had no radar.”

The crews of the SG-19 ships knew U-boats were in the area, and the weather was rough. Writing for The Providence Journal, Frank Lemon described this situation as “the ultimate cat and mouse game; the Americans knew the subs were there, and the subs knew the convoy was coming.”

Sure enough, one of the Coast Guard escorts was getting sonar of a possible sub in the area throughout the day.

The Dorchester's captain took the sonar seriously and instructed all men aboard to sleep in their clothes and life vests. Quarters were cramped and hot. Many men did not follow those instructions. Many felt comforted knowing they were about 100 miles from Narsarssuak, Greenland, thinking they were protected by aircraft hunting for U-boats. Narsarssuak, at the time, hosted “Bluie West One,” an airbase at the southern end of Greenland.

On the night of February 3, 1943, the ship was torpedoed by U-223, a German U-boat submarine in the Labrador Sea near Greenland. In “The Heroic Four Chaplains and the Sinking of the USAT Dorchester,” Logan Nye reported that the U-223 fired three torpedoes. Chuck Hill wrote,

“The U-boat had loosed five torpedoes, meaning she had fired all four of her bow tubes and turned and fired a single stern tube as well. One of the first hit the Dorchester. All the rest missed.”

The damage was severe. The torpedo destroyed the ship’s electric supply and released clouds of steam and ammonia gas. The Dorchester sunk in the frigid North Atlantic in under 15 minutes, taking about 675 men out of 902 on board.

The torpedo struck mid-section and exploded in the boiler room. Many died instantly. Some were trapped below deck. The ship took on water rapidly and began listing to starboard. This art by Dick Levesque, presented by the University of Cincinnati, depicts the Dorchester listing.

Lifeboats were overcrowded, and some sunk. Because of security requirements, the ship's crew could not employ distress flares. Uboat.net reported passengers began to abandon ship about three minutes after she was hit.

The American Veterans Center noted that only two of 14 lifeboats were successfully used. Many passengers jumped into the sea, which was icy cold then. Some lifeboats were overcrowded and capsized.

Just minutes after the attack, the captain of one of the escort ships ordered his crew to prepare for a rescue operation. However, the overall escort commander chose not to launch a rescue, fearing his ships might become vulnerable to more U-boat attacks. USCGC Tampa continued escorting the remaining ships

The USCGC Escanaba and USCGC Commanche began rescue operations right away. I have read accounts that said both cutters disobeyed the orders of the escort commander and went out on their own. This art, courtesy of the USCG History Office, depicts the rescue underway. William H. Thiesen, USCG Atlantic Area Historian, wrote,

“By the time Escanaba arrived on the scene, Dorchester had already begun its descent into the abyss. The seas were smooth due to a heavy oil slick and the wind was light. Dorchester’s life preservers were equipped with blinking red lights to help rescuers locate floating victims at night. These lights dotted the water’s surface into the distant darkness.

“Once on scene, Escanaba located its first group of floating survivors, stopped and drifted toward them. Some of the men were clinging to doughnut rafts, while others remained afloat using life preservers. The victims suffered from severe shock and hypothermia and could not climb the sea ladders or the cargo net. In fact, they were incapable of grasping a line used to haul them on board the cutter. Clad in his dry suit and secured to Escanaba by a line, (Second-class officer’s steward) Deyampert swam out to the floating victims and life rafts. He checked for signs of life and secured victims to a line so the deck crews could pull the survivors up to the cutter. Even though many victims appeared frozen to death, 38 out of 50 that appeared dead were frozen but still alive. The swimmers got the floating victims to the cutter immediately saving time and saving more lives. Thus, Escanaba could reach more victims before exposure froze them to death.”

Together, they rescued 230 men from frigid waters at night. U-223 escaped the scene.

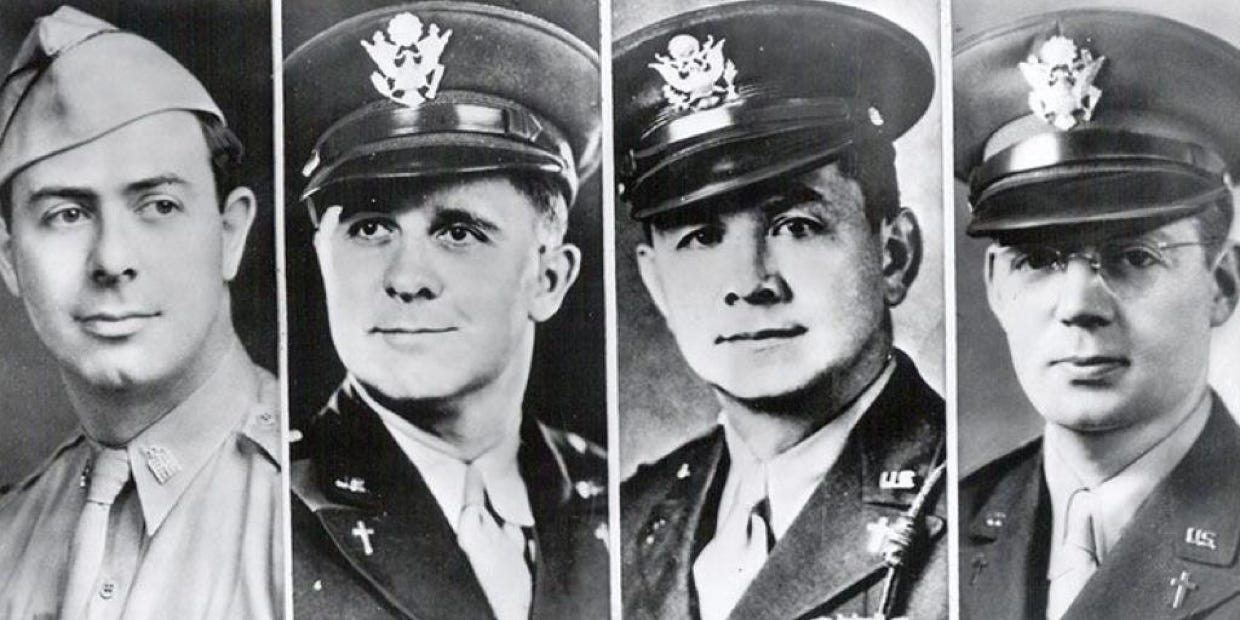

One of the lasting stories that would receive considerable attention in the US was the four Army chaplains aboard the Dorchester on this voyage. They were:

From left to right: Alexander D. Goode, a Jewish rabbi; Clark V. Poling, a minister of the Dutch Reformed Church; George L. Fox, a Methodist minister; and John P. Washington, a Roman Catholic priest.

The chaplains followed instructions. They had their life vests, and they were clothed when the ship was struck.

Joseph E. Schmitz, Inspector General, US Department of Defense, told the story that followed the XVI International Military Chaplains Conference held on February 9, 2005, in Ljubljana, Slovenia. Mr. Schmitz told it this way:

"On February 3, 1943, the USS Dorchester would become another statistic in the 'ships-lost-at-sea' column, but unlike others before it, what took place on the deck of the Dorchester would live on forever. At about 1 a.m., the USS Dorchester, a troop transport with over 900 service members aboard on its way to Greenland, was hit by a torpedo fired by a German submarine and sank in the icy waters of the North Atlantic. Many on board died instantly, while others were trapped below the deck.

"Chaos ensued – fire, smoke, and the screaming of the wounded. Fear filled the air. Some men panicked and jumped into the waters without life jackets; others were frozen in fear and refused to leave the sinking vessel. Taking on water rapidly, the ship began listing to starboard. Overcrowded lifeboats capsized, and rafts drifted away before anyone could reach them.

"In the midst of the confusion and terror, four chaplains – Protestant Ministers George Lansing Fox and Clark Poling, a Catholic Priest, Father John Washington, and Rabbi Alex Goode – moved about the ship, exuding composure while calming frightened men, directing bewildered soldiers to lifeboats, and distributing life jackets with calm precision. Soon, the supply of jackets was exhausted, yet four young soldiers, afraid and without life vests, stood waiting.

"Without hesitation, the chaplains removed their own life jackets and gave them to the young soldiers. Then, according to one survivor, the four chaplains joined some of the other men trapped onboard for prayers that ‘sounded like a babble of English, Hebrew, and Latin.’

"These four men of faith had given away their only means of saving themselves in order to save others. Men rowing away from the sinking ship in lifeboats saw the chaplains clinging to each other on the slanting deck. Their arms were linked together, and their heads were bowed as they prayed to the one God whom each of them loved and served.

"The Dorchester sank beneath the icy waters of the North Atlantic, carrying with it the four chaplains and some 675 servicemen."

Joy Neal Kidney's website provided some memories of one survivor, SSgt. Michael Calandriello, USA,

“The torpedo struck like a giant hand reaching out of the sea and puncturing a hole in the side of the ship. Forward motion stopped … Nothing in our training, however, had prepared us for the shock of the lifeboat tipping and dumping us over, to be engulfed by the frigid water … Soon, another lifeboat came by and picked me up. A Black crewman, Charley Wright, who had already survived previous torpedoings, took charge. With only three oars and all of us bailing furiously, we managed to stay afloat until we were rescued by the Coast Guard Cutter Escanaba.”

Steve Beard of Good News Magazine wrote the story “Life Vests and Torpedoes” and included the recollections of several survivors. I have highlighted some of those.

Walter A. Boeckholt recalled,

“I was thrown against the ceiling and then landed on the floor. By the time I was recovering my senses, the ship was already tilting. I grabbed for the door, which hadn’t jammed as of yet, and walked out on deck, realizing I didn’t have my life preserver, I went back into the room to get it. As I returned to the deck, they all seemed to be yelling, crying, and trying to get to their lifeboats. Most of the lifeboats were frozen solid or broken in the process of trying to get them loose.”

The National WWII Museum paid tribute to a Coast Guard sailor named Charles W. David, Jr. David was a Steward’s Mate. The Museum said,

“Witnessing the crisis, David and several other men voluntarily climbed down into the lifeboats where they helped lift the shivering men up onto the Comanche’s deck … The Comanche’s executive officer, Lieutenant Langford Anderson, fell overboard. Without hesitation, David dived into the deadly waters to save Anderson. David then helped lift a second shipmate, David Swanson, back onto the Comanche when Swanson had grown too weak from helping other men. Swanson recalled that David was a ‘tower of strength’ who shouted encouragement to his fellow sailors during the harrowing ordeal.”

Richard Sisk, writing for Military.com, said this about David,

“Steward's Mate 1st Class Charles Walter David Jr., 26, of New York City, known for his fierce loyalty to his ship and shipmates despite the second-class status afforded Blacks during World War II, jumped into the lifeboats and began hoisting the survivors aboard … In the course of the rescue mission, Lt. Langford Anderson, the Comanche's executive officer, slipped and fell into the frigid waters. Without hesitation, David dove into the icy sea, swam to Anderson's rescue, and brought him to the net.

“After helping the last survivors scramble aboard, David went up the net himself to the Comanche's deck, but his friend, Storekeeper 1st Class Richard 'Dick’ Swanson, could make it only halfway up, after being in the freezing water, according to an account by Dr. William H. Thiesen, the Coast Guard's Atlantic Area historian.

“From the Comanche's deck, David shouted encouragement: ‘C'mon Swanny, you can make it.’ But Swanson couldn't move. David went down the net again and lifted Swanson to safety.

Several weeks later, David died of pneumonia at a hospital in Greenland from the hypothermia he suffered during the rescues.”

Richard Sisk also provided comments made by William Bednar, a survivor, who said, “I could hear men crying, pleading, praying and swearing. I could also hear the chaplains preaching courage to the men. Their voices were probably the only things that kept me sane.”

The website continued, “Survivor John Ladd recalled the chaplains giving away their life vests, according to the Four Chaplains Memorial Foundation. ‘It was the finest thing I have seen or hope to see this side of heaven,’ he said.”

Returning to the Good News article, James Eardley recalled,

“When she rolled, all I could see was the keel up there … We saw the four chaplains standing arm-in-arm … like they were looking up to heaven, you might say. Then the boat took a nosedive. It went right down, and they went with it.”

Grady Clark put it this way,

“As I swam away from the ship, I looked back. The flares had lighted everything … The bow came up high and she slid under. The last thing I saw, the four chaplains were up there praying for the safety of the men. They had done everything they could. I did not see them again. They themselves did not have a chance without their life jackets.”

Frank Lemon, writing for The Providence Journal, quoted Naval historian Samuel Eliot Morison,

“When additional rescue ships arrived on February 4 …hundreds of dead bodies were seen floating on the water, kept up by their life jackets.”

Benjamin Epstein said it this way,

“To take off your life preserver meant you gave up your life … You would have no chance of surviving. They knew they were finished, but they gave it away. Consider that. Over the years, I’ve asked myself this question a thousand times: Could I do it? No, I don’t think I could. Just consider what an act of heroism they performed.”

There were 230 survivors.

US and British naval ships found U-223 northeast of Palermo, Sicily, on March 29, 1944. Together, they attacked and sunk her.

Chuck Hill wrote that Escanaba blew up and sank on June 13, 1943. Only two survived, with 103 lost.

Over 700 merchant ships were sunk in WWII. More than 9,000 mariners were lost. The Germans and Japanese sunk six Merchant Ships before the US entered the war. The National WWII Museum highlights,

“Members of the Merchant Marine faced terrifying conditions moving goods and troops … The often slow-moving ships—and the civilian merchant mariners who maneuvered them—were easy targets for enemy fire … Eleanor Roosevelt proclaimed, ‘Without our Merchant Marine, this war could not be won, and it is greatly to our interest to make the life of our merchant seamen a worthwhile existence in the future, because I believe we are going to need our ships to sail the seven seas.’”

In 1960, Congress created a special Congressional Medal of Valor, never to be repeated, and gave it to the next of kin of the "Immortal Chaplains." The loss of Dorchester and her men was the third largest loss at sea for the US during WWII.

__________

Click to zoom graphic-photo